She died without receiving the justice she had long fought for. She died without getting assurance that her sacrifices in coming out to tell her story was not in vain.

Lola Rosa Henson was one of the thousands of women in the Philippines forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II.

Other Lolas who had suffered like her brought their tormented tales to their graves. But not Lola Rosa. She was the first woman to tell the world about this inhuman practice of the Japanese during the war.

She and other Asian sex slaves, euphemistically called “comfort women” by their captors, had kept silent for nearly 50 years after the war. But then, in the 1990s, they gathered the courage to go public and face their scourge.

The public revelation

The appeal for Filipina comfort women to come out and to stand up for their rights came from Nelia Sancho, a member of the Task Force for Filipina Military Sexual Slavery by Japan.

The movement to document the comfort women issue in Asia was begun on Oct. 17, 1990 when 37 women’s organizations in the Republic of Korea joined forces to make formal demands that Japan apologize for its crime and compensate the victims.

The decisive moment came when one victim, Kim Hak Soon, came forward in Seoul in the summer of 1991 and demanded that Japan take responsibility. Kim was the only complainant to use her own name in a lawsuit demanding compensation for Pacific War victims.

The lawsuit was lodged in December 1991. The movement gathered momentum across the Asia-Pacific region, including the Philippines, Sancho spearheaded the call on behalf of Filipina victims.

At first, Lola Rosa hesitated. Just like many other Lolas, she feared the stigma and possible ostracism once she admitted in public what had happened to her. Then, on Sept. 18, 1992, she decided to come out with her story, and to tell everyone what happened to her, with the hope that such an ordeal will never happen again to any woman.

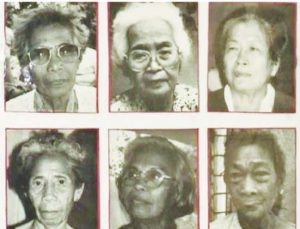

Lola Rosa’s brave move to come out encouraged others. In all, the Filipina comfort women who followed Lola Rosa’s example numbered 169 – a minute portion of the more than a thousand Filipinas and nearly 200,000 Asian comfort women who suffered systematic rape, torture, imprisonment and death at the hands of the Japanese Army during World War II.

Born on Dec. 5, 1927, Lola Rosa was barely 15 years old in 1942 when she was raped twice by a Japanese officer in what is now Fort Bonifacio. In 1943, she was captured by Japanese soldiers and was taken to a garrison in Magalang, Pampanga, where she became a sex slave for Japanese troops for nine months until she was freed by the Hukbalahap in 1944.

“There was no rest, they have sex with me every minute. That’s why we’re very tired. They would allow you to rest only when all of them had already finished. Due to my tender age, it was a painful experience for me. Sometimes in the morning and sometimes in the evening – not only 20 times,” Lola Rosa said.

Calling her “maestra” or great mentor, the rest of the surviving comfort women vowed to continue what Lola Rosa started. During a news conference held two days after Lola Rosa’s death on Aug. 18, 1997, fellow “comfort woman” 70-year-old Pidencia David told reporters that Rosa will always be remembered as the personification of what the comfort women are today: fighting until death.

“Sana naman ay ibigay na nila ang aming ipinaglalaban hanggang hindi pa kami nauubos [I hope they grant what we are fighting for before we all die],” David said.

Collective Movement

Lola Rosa’s autobiography has been published in a book titled Slave of Destiny. It is now being used in some classes in Philippine universities.

On April 2, 1993, 18 comfort women from the Philippines filed a lass suit with the Tokyo District Court against the Japanese government. Lola Rosa was the first to testify. Two other Lolas from Bicol – Lola Fe Hedia (who died in December 1996) and Lola Felicitas Jampolina – also appeared in November 1996 and gave their full testimonies in court. Lola Rosario Nopueto, 70, and Lola Julia Porras, 68, and 70-year-old Lola Cristela Alcober gave their testimonies in June 1997.

Lola Julia testified that she was only 13 when Japanese soldiers held her captive in a tunnel where dozens raped her every day. She was fed only a bowl of rice three times a week and no clothing was provided for her. Lola Cristela had expressed that the 16th hearing of the suit gave her more hope in continuing with their campaign: they expected the court to render its decision early the following year. The 18th and last hearing was held on Sept. 19, 1997, where the three Lolas again testified.

On Oct. 9, 1998, the Tokyo District Court dismissed their complaint. Some of the Lolas included in the lawsuit had died even before the ruling was handed down.

The Lolas lodged appeals to the Tokyo High Court on Oct. 23, 1998, which also rejected their appeal on the ground that individuals cannot sue the government for compensation. On Dec. 25, 2003, the Supreme Court rejected the final appeal, and the case was closed.

They may have lost their own case but the movement won a bigger victory when the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal in Japan convicted the war criminals, including Emperor Hirohito, as the leader of the country who was ultimately responsible for the sex slave policy.

The marathon hearing was held from Dec. 8-12, 2000 with 35 out of 64 plaintiffs from eight countries who testified in person. The decision was handed down at The Hague, Netherlands on Dec. 4, 2001.

Nelia Sancho, now the national coordinator of Lila Pilipina, said that Lola Rosa started a collective movement among the Filipino “comfort women” and highlighted the violence suffered by women at the hands of soldiers during war.

“More than marking the end of World War II, we demand an end to all wars and forms of armed conflict that have brought immeasurable violence and suffering to the lives of millions of women victims. …And a crucial step toward peace is making governments accountable for war and the human-rights violations committed against women in the name of war and the state.” Sancho said.

Ken Arimitsu of the Citizen’s Fund for Redress of World War II Victims in Asia and the Pacific, based in Japan, expressed in a letter that Lola Rosa’s actions were important for the human-rights movement in the world.

“By her courageous coming-out and her testimonies, we learned the real history in Asia,” Arimitsu said.

Asian Women Fund

In July, 1995, the Asian Women Fund, was put up by the Japanese government from its citizens and private corporations. It aimed to raise Y1 billion from individual and corporate donations to compensate comfort women claimants. The Lila Pilipina has opposed this fund since they see it as the Japanese government’s way of weaseling out of its legal responsibility to officially compensate the victims.

Lola Rosa and some other Lolas accepted assistance from the fund. Most of them were poor and many at that time were then in poor health and needed finances for their health care.

Lila Pilipina was rocked with controversy as a result. Sancho said, however, that they respect the decision of the Lolas, stressing that the position of the Lolas is independent of Lila Pilipina as an organization. In fact, Sancho pointed out that some of those who favor the fund and who accepted it to finance their medication and other needs were still active participants in the activities of Lila Pilipina.

The AWF has also organized activities to ensure that the comfort women issue will serve as a lesson of history, and to raise awareness of the issue. The activities have been based on a determination that, through historical research and education, the Japanese people will never forget the issue or repeat the same mistakes. The disbursements of the funds ended in 2007.

Supporters of the comfort women worldwide stress that informing the youth about sexual slavery during war will help in the victims’ recovery and prevent its recurrence. International support for the comfort women’s cause has been lukewarm.

So far, only the South Korean government has officially lent its support to the campaign in pressing the Japanese government for official apologies and state compensation for women survivors as well as a comprehensive assistance program including providing the women with housing, medical and financial support.

The Philippine government not only failed to give recognition to the comfort women but in 2018, it goes down in history as the only country to remove the statue memorializing the comfort women yet allowing the Japanese their shrines to memorialize soldiers who raped and killed Filipinas.

Today, 73 years after the war, the Japanese government still refuses to recognize its official accountability to the victims of sex slavery. The three demands of the Lila Filipinas have not been met: admission of the tragedy and official recognition of comfort women, formal apology and reparations and re-writing of textbooks to incorporate the comfort women into accounts of war atrocities. — Inputs by lawyer-historian Dennis R. Gorecho is from “Remembering Lola Rosa Henson,” written for his Mga Kwento ni Kapitan Kokak Blog, Dec. 2, 2010, https://kapitankokak.blogspot.com/2010/12/remembering-lola-rosa-henson.html?m=1.

(Tulay Fortnightly, vol. 30 | No. 23, May 8-21, 2018)