I first heard about comfort women in a conference on Asian Relations in Korea. They had invited a comfort woman to talk about her experience during the Japanese Occupation. I felt the tension as the translator attempted to censor the woman’s anti-Japanese sentiments because there were Japanese delegates present but we were all moved by the atrocities she had lived through. We felt her rage with an understanding that surpassed language, and collectively felt relief when their voices were heard.

The Korean government supported the plight of the comfort women, they emerged through the darkest parts of history with the healing hand of their country. As the woman wound down her speech, she mentioned that the others have not been as lucky. The ones from Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia are still struggling to be recognized.

It was then that I decided to change my thesis altogether and focus on the plight of the Filipino comfort women. It was a bold move with only a month to go, but I was determined to see it through.

I scourged the library for mentions of them. Philippine history books have always been scarce as historical scholarship is not heavily encouraged in our education system. The ones that they taught in secondary school have been scrubbed by Americans.

There were wars that were omitted or glossed over, the Philippine-American War and the heavy death toll of our troops remain largely unexplored. The Vietnam War and the My Lai Massacre and so forth. So it was a huge surprise when I found a section about the comfort women in the American Historical Section of the library for literature.

The books gleaned on the logic behind the comfort stations of the Japanese forces. In order to understand this, we begin with Nanking (Nanjing), the last stronghold of China.

In 1937, Shanghai had already fallen after the Imperial Japanese army’s Pyrrhic victory. The Japanese forces decided to capture the then capital Nanking, perhaps to have a decisive victory once and for all. The Chinese refused to surrender, and its defense army (largely untrained) blocked roads, destroyed boats, and burnt nearby villages, to prevent widespread evacuation of the city’s residents.

After weeks of fighting, the Japanese finally won and they took out their aggression on the hapless citizens whose only crime was to be caught in the middle of a war. They forced fathers to rape their daughters, and women were treated worse than animals with large items inserted into their privates. Two soldiers even competed on how many they could kill with a sword.

The population was tortured mentally and physically before they were given the solace of death. A negative backlash for the massacre ensued, and the Japanese sought to control the aggression of their troops by putting up comfort stations in which they were free to prey on women any day of the week.

They reasoned that the “ianjo” (comfort women brothel) would encourage more men to go to war, as well as a means of stopping the spread of venereal disease at the cost of the countries which they have occupied under the guise of the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere.

My search for the comfort women eventually led me to a publication by a former beauty queen, Nelia Sancho, who compiled the stories of the women in 2001. Sancho was an activist during Martial Law and was imprisoned for two years during the height of her career.

Her book details the harrowing experiences of the comfort women. A handful of them were barely in their teens when they were abducted from their homes and forced to live in the harsh conditions of the comfort stations. They came in with the clothes on their backs and left with the clothes on their backs: they were never given any piece of clothing, not even a towel. Through countless months of abuse, their skirts and shirts were torn over and over again that some of them emerged naked when the Japanese troops finally fell.

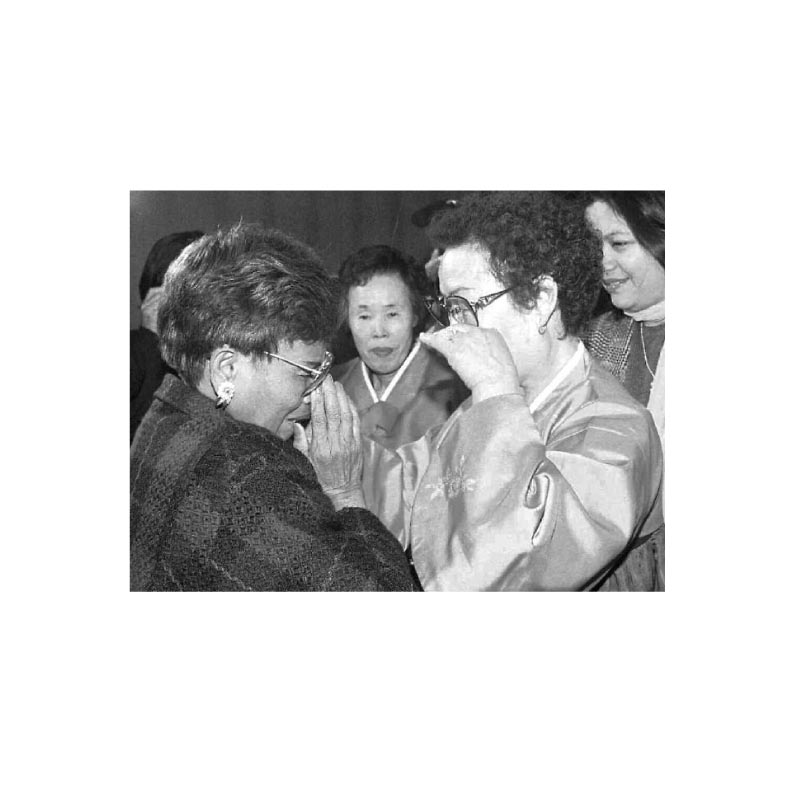

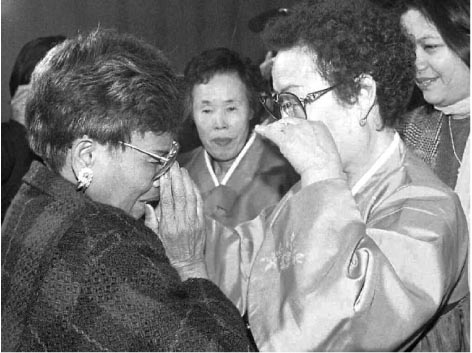

It was a moving piece of literature but I was curious because of the formatted way of their testimonies. It usually began with a statement, their age, what they were doing before they were captured, their life in the comfort stations and ending with healing and finding a man who accepted them. I felt that there was more to their story so I contacted Sancho, who was kind enough to arrange a meeting with a comfort woman, Julia Porras.

Nanay Julia is a lovely lady, her sole wish was to appear in the then hit noontime show, “Wowowee” to bring awareness to this part in history. She recounted how she saw the Japanese soldiers approaching and she decided to jump from their house but her leg caught on the bamboo pole. She never saw her family again.

When she was taken to the garrison, her eyes were subjected to the glare of the flashlight for 30 minutes, she could not tell where the soldiers were leading her and three other women. She was led to a cell, no bigger than a bathroom and repeatedly raped, she lost count of the days.

She shared one song with me that she always heard, a Japanese song which I later asked my friend to translate. It was a song of morning and the red sun and the sky and how people have to get up. Surprisingly, Nanay Julia added on an English version which talks about her healing journey.

“I escaped, while prisoner, up and down, the zigzag grills” she sang to the same tune of the Japanese melody. “Onward to the reverie, my mystic girl. I pursue her and brethren and painfully, I don’t mind. Open just, injustice sleep, my dearest one.”

It was there that she found her voice, the one that cannot be contained in a narrative, the raw history and memories that cannot be silenced or forgotten.

Up to this day, a number of Japanese historical revisionists claim that comfort women were not real, that they were licensed prostitutes operated by privately owned brothels. In this light, the Japanese government does not have any accountability.

A movement called Free History was also set up by Japanese historians denouncing the claims of the comfort women due to a lack of sufficient evidence in order to merit authentic scholarly claims of existence. The women are thus silenced and shamed over and over again, as if history had not done them wrong.

Some private Japanese citizens set up the Asian Women’s Fund to give compensation to the comfort women. Because this is a private fund, the government still manages to dodge accountability for what the troops did to these women. Until this day, the Japanese government still refuses to acknowledge comfort women.

Nanay Julia claims that Japanese are waiting for the women to die out so they will be silenced forever.

The Korean government demanded six conditions for the comfort women: that the Japanese government should issue an apology, the government should reveal all their brutal acts during the war, that there should be legal compensation, that there should be historical documentation so that these acts would not be repeated and finally, that a monument should be erected to honor the women.

This is exactly why the monument of the comfort women in the Philippines is a victory for all women. Even without government support, we still stand. Even with the threat of being forgotten, being shamed and being silenced, we fight on. We stand in stone, we stand for our part in history, we stand against domination and revisionism. We stand for ourselves.