The UBER driver was about to arrive when, suddenly, signs of rain hovered as fierce winds whipped tan ancient acacia tree under which I took shelter. The wind scattered hundreds of leaves – a wonderful sight as the confetti flew towards the deserted street that stretched in front of me towards the paifang (牌坊 memorial arch) a few yards away.

I began to imagine what the old man Eng Kun Guan would be feeling now if he had been in my shoes at this very moment, waiting here where his parents and brothers lay. Staring at the paifang, hopeful but unsure when his lost living kin would visit, if he would ever be able to meet them in this resting place.

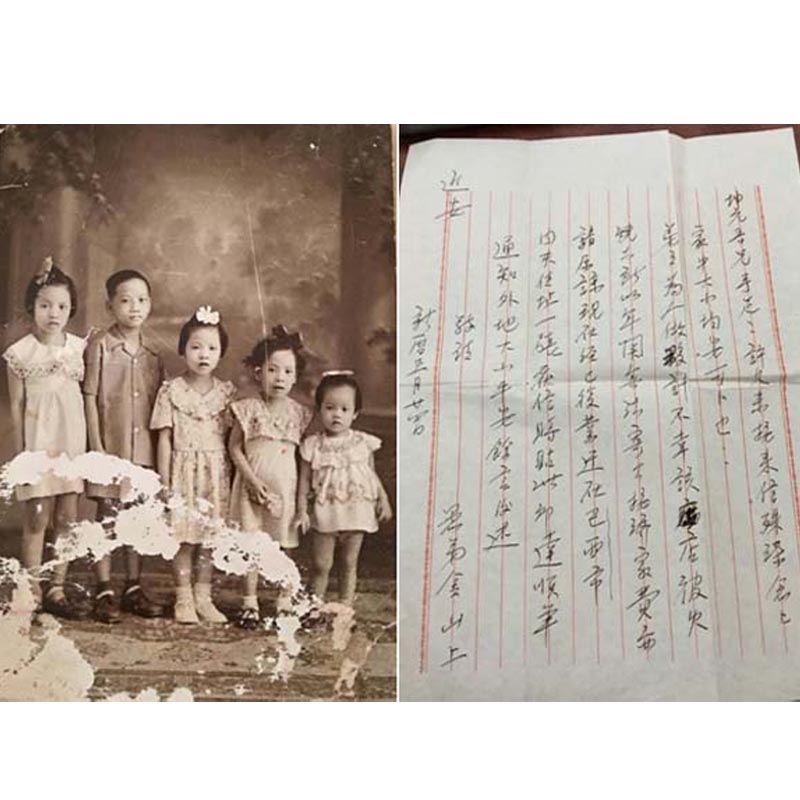

This quest started with a family photo and a family’s cry for help to find the people in that photo. What followed was a journey with twists and turns as well as unexpected hurdles. But at the end of the journey was comfort and joy for a successful search.

A journalist once asked me how I make these finds possible. The simplest answer – an innate desire to help others is the driving force. I do not earn anything from my self-appointed “relative-finder” task and, in fact, out of my own pocket expenses pile up at times. But this passion to help reconcile long-lost family and the psychic rewards from a successful find make this advocacy worth it.

#ChinoyLife

I learned about the Eng family’s search for their lost siblings in the Philippines in a Facebook online forum called #ChinoyLife. On May 31, 2016, Nathan Co posted a public service announcement about Eng Kun Guan, an old man in China who has been looking for his brother Eng Kim San and other siblings here in the Philippines.

Several members responded to the cry for help. Some approached hometown associations while others checked clan associations. I observed the progress from the thread of posts but no one could give leads. I kept thinking of ways to also help in the search.

I felt sad to learn of Eng Kun Guan’s story. He was left in the mainland while his family went overseas. It was heart wrenching to know he lost touch with his immediate family for so many decades. I have reunited so many families and I could relate to the struggles families go through with these separations.

Father Eng gives clue

I was taking Mandarin classes at Confucius Institute at the Ateneo de Manila University when Eng’s search was posted. One of the effective methods I use to memorize Chinese words is Panda mobile application which churns out characters in a flashcard format. Eng Kim (黃金, gold) was a random character the app flashed out for me to guess. It reminded me of the first name of Eng Kim San (黃金山, gold mountain) the missing brother and I felt as if the dead was inviting me again to help them. It was akin to what I felt when I was looking for Nathan Co’s ancestral village. I had a Eureka moment! I can use the same method to find clues about the Engs – through existing records of the dead.

The last known address of the Engs was in Binondo and communication ended around the time his father died. The family moved when their residence burned down. I speculated that Eng’s father must be buried in Manila’s Chinese Cemetery and there would be a record in the Philippine Chinese Charitable Association that manages the cemetery.

I visited the cemetery admin office on July 5, 2016 and found he was indeed interred there. Mary Lee, the old lady in charge of cemetery records, provided the tomb’s location and the name of the caretaker who will be able to give me more information.

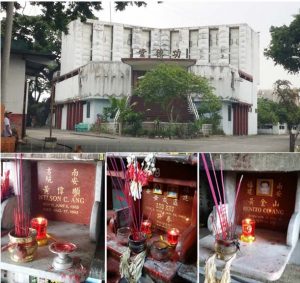

Excited, I went to visit the cemetery and went straight to the temple and asked for the caretaker Ting. Ting immediately pointed me to Kong Tek Tong (功德堂), the building next to the temple. In the dark alleys of the first floor of the old cramped columbarium his cigarette lighter helped us locate Eng Le Khu’s tomb.

He said that several Chinese ladies still visit the tomb regularly. He even recalled what favorite food the ladies brought as offerings. Could they be one of the girls from the old photograph? The small tomb marker bears the father’s and mother’s names. The mother had just died in 2011.

Ting called his fellow porter and nephew Jongjong, who said these ladies also visit two other tombs. Jongjong guided me to the building opposite Kong Tek Tong, where on the second floor was the tomb of a certain Wilson Ang. Jongjong said the deceased is a son of Eng Le Khu.

He led me to the 3rd floor. The third tomb was that of Eng Kim San himself! He died in 2010. I felt extremely sad knowing the person we were looking for had already passed away.

I sent a WeChat friend request to the contact number in the Facebook post and immediately got accepted. I broke the news immediately through the pictures I took from the Chinese Charitable Association up to finding the tombs.

The mobile number belongs to Eng Muy Hong, Eng Kun Guan’s daughter-in-law.

My news brought her hope as I relayed that living relatives still visit the tomb. Perhaps, the old ladies who visit are Eng Kun Guan’s sisters from the old photo he kept.

The letter

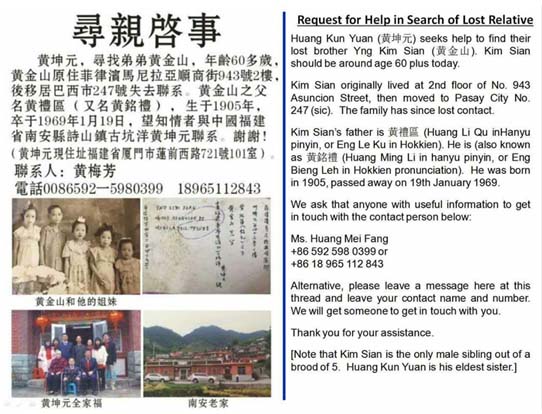

I wrote a letter addressed to the descendants of Eng Le Khu. I printed three copies, one for each of the tombs, put them in plastic envelopes and weighted down my letters as we had to wait for several months leading to All Souls’ Day. I also offered some cookies so perhaps the deceased would be happy and provide good luck to our endeavor.

In the letter, I explained about Eng Khun Guan’s futile 10-year search for his siblings and how I was able to find their records through the Chinese Charitable Association. I wrote that Eng Khun Guan wished to visit the Philippines and pay respects at his father’s and brother’s tombs. I also enclosed copies of Tulay chronicling my other successful endeavors reconciling relatives.

After I laid the letters on the graves I asked the two porters to message me if and when relatives would visit. Ting said one possible date was Aug. 17 which is the birthday of Eng Kun Guan’s deceased brother Wilson Ang.

On the day of the birthday we waited for news from the two porters. But no one came. Perhaps during All Souls’ Days, Ting said reassuringly.

The unknown brother

One Saturday morning, a week before All Souls’ Day, I woke to see a lot of missed calls from Ting. A man who said he was related to the family had just visited the tomb and took all three envelopes in front of the graves. He gave me the name William Ang as well as his number. I immediately called and asked if he was fluent in Hokkien; he was. I asked if I could give his number to his relatives in China. Eng Muy Hong was very ecstatic on hearing the news and they immediately called William. My work is done! Or so I thought.

A few days later, I received feedback from Muy Hong that they were planning to visit the Philippines in a few weeks’ time. But William has stopped responding to their calls. I sent messages but received no response.

I searched online for William’s Facebook account and found it had been inactive for a while. I looked at his Facebook friends and found his wife. Initially, our conversation went fine. But when I mentioned about the relatives arriving, her tone changed and she said that I should clean up the mess that I’ve started and that they’re too busy to meet their relatives. In all my cases, I’ve never dealt with such deep suspicion. I felt angry and humiliated and was about to give up. But Eng Kun Guan’s ordeal and helping him in this long search for his lost family mattered more than this relatively minor setback.

There is always suspicion from Philippine relatives as to the reason why their China relatives suddenly want to touch base with them. There had been some unpleasant stories about China relatives appearing out of the blue and demanding their share of the family business left by their ancestors. I was in a quandary. I thought, if the family here is notinterested to meet them, then I will be the one to meet Eng Kun Guan and guide him to visit his parents’ and brother’s resting place. One day, Muy Hong asked me a favor. She sent me a very lengthy message (838 words) that I should relay to William. I asked a friend to translate the message.

Muy Hong’s message explained how they had been searching for their Philippine relatives and detailed the efforts they expended for a decade. She assured her relatives that those traveling from China will take care of all expenses, airfare as well as board and lodging in the Philippines. The letter also invited the Philippine relatives to visit them in China and they will entertain them. Muy Hong’s message strongly hinted the family was well off, owned a car and could drive them around.

Part of it reads:

Below are some words we would like to bother Uncle to convey to your two daughters: “My two beautiful sisters! How are you! I am your sister-in-law. Even though we are aware we have tens of relatives in the Philippines, we have so far only seen the photos of your family of four, and still do not even know your names. But I hope you can visit us at the earliest. Our hometown is very beautiful! Now we live in Xiamen, Fujian. When you visit, I will personally drive a car to bring you to your ancestral home. Xiamen to Ku Kheng (now known as Min Chu town) is about an hour’s drive. We look forward to seeing you soon! If you can message me it would be most ideal. My phone number is my WeChat number.”

Apparently, that lengthy SMS made all the difference to allay Philippine relatives’ fears. Her uncle William started responding.

Success

A few weeks later, I received a call from Co Yok Din to verify if indeed I am a writer from Tulay. This caution reflects the long-standing fear some Chinese families have regarding criminal activity, particularly kidnapping.

I connected Eng Muy Hong with Yu Chun Sing (楊春勝) whom I recently helped find relatives in the Philippines. He guided her on travel requirements and tips for their visit to the Philippines.

Muy Hong invited me to meet them at Ramada hotel. I saw her and her new-found Philippine kin and they all looked very happy! As I had to work that afternoon, I left early. Muy Hong saw me out and held my hand as she continued to thank me with many words of gratitude which I did not fully understand. She waved goodbye until I finally disappeared from her view.

I thought the encounter ended there until I received the booklet, In Search of Overseas Relatives (海外尋親), where Muy Hong documented the arduous journey in search of her kins in the Philippines.