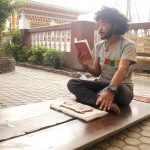

MigmarTsering, 25, is from the remote province of Nubri, Nepal. He sports an afro hairstyle, a swag beard and a charming smile, and an earring on his left ear. He carries a chic, leather backpack.

When I first spotted him, he was bowing full-length on a plyboard, in front of three Buddha statues. He has bowed, or prostrated, 3,000 times already, he said. Only 97,000 more to go.

Prostration involves bowing to the ground or bowing on your knees, with forehead touching the floor, to pay reverence to a holy or venerated person or object.

One of Buddha Shakyamuni’s past lives was of a wealthy merchant named Sumedha who gave away all his wealth and left his old life for good. When Dipamkara, the Buddha of that era, passed by in front of him, Sumedha flung himself to the muddy ground, allowing Dipamkara to pass through without staining his feet. Thus was the idea behind prostrating born.

Traditionally in Buddhist practices, one prostrates three times before entering a temple, or upon seeing one’s master. It is even used nowadays to punish erring monks, young and old alike (I know a mid-adult monk who had to do 150 prostrations for breaking monastery curfew!).

But there also exists the tradition of accumulating 100,000 prostrations (plus 10 percent interest to cover up for the forgotten, miscounted and so on).

In Nepal, this tradition is still alive. It is done not just by monastics or conservative, old people stuck in their pre-radio era, but by millennials like Migmar, who keep track of the number of prostrations on their Facebook and Instagram Likes.

Prostration in numbers

A hundred thousand full-body prostrations would take at least 45 days for the average man (without any day off). A diligent one who manages 3,000 bows per day can finish in maybe 36 days. And if in an hour one does, on average, 400 prostrations, it will take eight hours to achieve 3,000, including a few breaks in between.

Not to mention the physical pain: every hour is like playing Russian roulette – one never knows which body part will ache next.

In the world of resumes and LinkedIn, it is a completely useless and unrecognized “effort.” Imagine Migmar telling his would-be employer, “Sir, for two months I did 100,000 prostrations.” It is simply not considered a “worldly” endeavor.

Ideally, a Buddhist practitioner commits one’s self to gain sonam (Tibetan term for merit) and attain enlightenment. It is done as part of a set of preliminary practices in order to receive “higher” teachings in the future.

One may learn from a mix of inspirations, such as from a teacher’s guidance and from doing a pilgrimage.

The experience

Swayambhunath is a Buddhist holy site in the heart of Kathmandu, Nepal. With its three magnificent Buddha statues, lush greenery and ample benches, it attracts Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike.

The Buddhists circumambulate the statues while counting their prayer beads. They also do prostrations. Visitors, armed with selfie sticks, take selfies and groufies.

Migmar normally begins his prostrations at dawn, at 5:30 a.m. He will be alone for the entire day. Occasionally, there may be some fellow Buddhists beside him, but they only do a couple of hundred prostrations. They come and go.

From sunrise to sunset, Migmar repeatedly goes through five movements, placing his folded hands on his 1) forehead, 2) throat and 3) heart, 4) bowing down and 5) pushing himself up.

Modern technology and globalization do the counting of prostrations. The traditional 108-bead mala (Sanskrit for rosary beads), used to keep track of each prostration done, can be replaced by an electronic Tamagochi-like counter. The plyboards are donated by a Taiwanese Buddhist group thousands of miles away.

There is also the iMala, a smartphone app which keeps track of the total accumulated mantra one has chanted and calculates the remaining number of days needed to accomplish one’s set goal.

But this does not keep Migmar entertained for long. Boredom often creeps in. Since he started, three hours have passed. His tank top is now drenched in sweat. He had had his breakfast, snack and toilet breaks. While prostrating, endless thoughts, memories and plans arise. It is a constant struggle to leave them aside.

The idea of enlightenment is one saving grace of Buddhism. Although it is bound by a lot of rules, morality and ethics, enlightenment relaxes them all. Ironically, one needs to undertake all these efforts to achieve that goal. According to the masters, this is because enlightenment is too simple for our complicated minds. So we need immense effort to achieve the simplest of wisdoms.

Throughout the day, Hindu Nepalis stop and stare at him (only 15 percent of Nepalis are Buddhists). In Nepali culture, staring is not considered rude. Some even approached him and took photos of Migmar while he is prostrating.

I asked him about the stop-and-stare strangers. He said that he ideally has to visualize the Buddhist Refuge Tree in front of him whilst prostrating.

The Buddhist Refuge Tree contains numerous Buddhas assembled and seated together. The purposes of visualizing such an image are manifold, but essentially, it is to get one’s mind accustomed to something holy and venerated. He confesses that the visualization is extremely difficult to maintain amidst the crowd.

It is now 4 p.m. and Migmar is about to finish for the day. As he wipes the sweat off his forehead, he admits that 3,000 a day is an impossible task, so he has resigned to finishing it in more than two months. He then flashes his signature smile, mixed with a little guilt.

Epilogue

Serious Buddhist practices such as prostrations are very potent means to achieve the goal of enlightenment. However, a person needs a qualified Buddhist teacher before undertaking such practices. This is because such efforts fall outside our usual norm.

Normally, after accomplishing 100,000 prostrations, the practitioner’s tendency is to brag about his success – another medal in one’s “spiritual” resume. However, Jamgon Kongtrul, a 19th Century Buddhist master, warns practitioners of the pitfalls of bragging about one’s “spiritual” achievements, or practicing for show, criticizing those who seem to be doing less than oneself and many others. The teacher serves as a guide so that the student stays true to these ideals.

Conclusion

The tradition of prostrating 100,000 times is a foreign concept to us, but its basic premise is not wholly unfamiliar. As mentioned before, the last thing such Buddhist practices ought to inspire are pride, competitiveness and showmanship.

In fact, according to the masters, one measure of success is that one’s pride and self-importance have decreased. But the best sign to expect after completing it? Amidst the sweat, tears and boredom, there is a subtle urge growing within the practitioner to undertake a second 100,000.

In a few months, we will know if Migmar has ‘succeeded.’