Names tell stories. In history, names sometimes speak of a whole era.

Such is the case with Koxinga. Pirate or hero?

In the Philippines, many know him as a famous Chinese pirate. Many books and articles portray him as such. And this image may well have sprung from his brief brush with the Spanish colonial government during the 17th century.

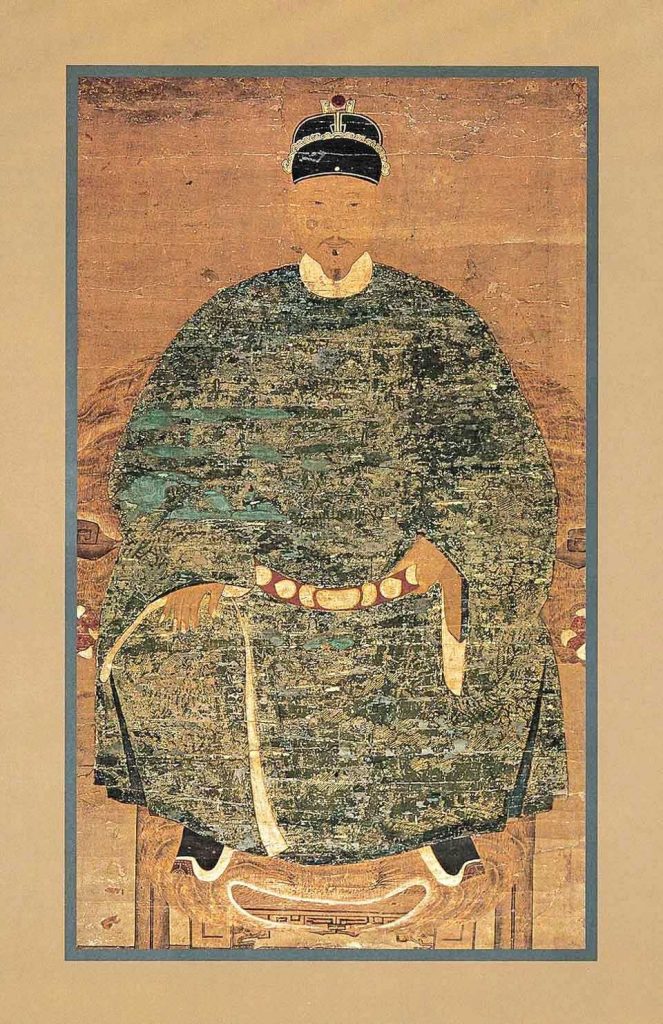

In truth, Zheng Chenggong (鄭成功), more popularly known as Koxinga (1624-1662), was a famous Chinese national hero honored on both sides of the Taiwan Strait.

In Taiwan, the admiral is honored for having driven away the Dutch and liberating the island in 1662 after 38 years of Dutch occupation.

Meanwhile, mainland China gives importance to his efforts in unifying China during his time, and now plays up Koxinga’s role in its own efforts to reunify Taiwan and China.

A huge stone statue of Koxinga in Xiamen’s Gulangyu (鼓浪嶼) faces Taiwan, a symbol of these efforts.

A military man, Koxinga was famous for his armed defense against the invading Manchus in the waning years of the Ming Dynasty (1368-16440). For this, the Ming emperor conferred on him the royal surname.

Thus, he was called Guo Xing Ye (國姓爺), meaning lord of the imperial surname. Guo Xing Ye came to be pronounced as Koxinga in the Western language with a little variation of the original.

After he drove out the Dutch from Taiwan, he took over the island and used it as a base for the next 16 years in his campaign to drive out the Manchus’ Qing Dynasty.

In 1661, Koxinga’s troops landed at Lu’ermen to attack Dutch colonists.

On Feb. 1 the following year, Taiwan’s Dutch governor Frederik Coyette surrendered Fort Zeelandia.

In the peace treaty, Koxinga was called Lord Teibingh Tsiante Teysiancon Koxin, effectively ending Holland’s hold on Formosa.

Koxinga was born in Japan to a Chinese father, Zheng Zhilong (鄭芝龍), and a Japanese mother, Tagawa Matsu.

“Zheng Zilong, native of a poor family from Nan An (南安) county in Fujian, went to Macau at a young age and was baptized there with the Christian name Nicolas Gaspard. He later went to Japan and married a Japanese woman who gave birth to Koxinga,” according to Luis Pfister, in his famous work Biographies of Jesuits in China during Ming and Qing Dynasties, Johann Adam Schall Von Bell.

The elder Zheng became famous marine merchant. And in those days, marine merchants in southern China’s coastal areas, just like the European marines since 16th century, were both merchants and pirates.

The impression and projection of Koxinga as a pirate among Westerners was mainly due to his father. Koxinga’s own career was mainly as a general who led the fight against the Manchus in mainland China and later against the Dutch who occupied Taiwan.

But how did Koxinga enter into the picture of Philippine history?

On April 21, 1662, he sent a letter to then Spanish governor general Don Subiniano Manrique de Lara, threatening to attack because the Spaniards treated the Chinese in the Philippines very badly.

But the attack never happened. Soon after he sent that letter, Koxinga, at 37, died of illness.

Nevertheless, Koxinga’s threat considerably alarmed the Spanish colonial authority. In response, De Lara ordered the reinforcement of Manila. Esteban A. De Ocampo’s The Ternateños, their History, Languages, Customs and Traditions narrated that:

“Fearing an invasion from Koxinga, he ordered the Spanish soldiers to abandon Zamboanga and other parts of Mindanao as well as that of Ternate in the Moluccas (Islands) – which had been taken by the Spaniards in 1606 – and to reinforce the menaced capital, Manila.

“The garrison of Ternate thus transferred to Manila in 1663, and with it probably was a contingent of Mardica warriors. It was mentioned that “200 Mardicas had left Ternate (in the Moluccas) for Manila. In (Manila), they established themselves in Bagumbayan or what is now Ermita.”

The Mardicas settled in what is Ternate (in Cavite) today, or what was formerly called Barra de Maragondon probably not later than 1700.

De Ocampo further writes:

“Upon their arrival at the coast of Maragondon River, which they called Gala-la, taken from the name of a tree which grew in that place, the Mardicas cleared the land and tilled the soil.

“Being near the river and the bay of Manila, they engaged actively in fishing which, up to the present, is their chief occupation.

“In due time, they intermarried with the people of the neighboring villages and when their community was organized into a pueblo or town, they chose the name Ternate in memory of their far away home in Moluccas Islands.”

Thus, a new town in the Philippines was born as a legacy of a letter from Koxinga.

However, Koxinga’s link to Philippine history is not limited to this incident. Records show that he visited the country as a child.

Pfister said the child Koxinga went to Manila accompanied by a Spaniard and then to Taiwan by a Portuguese.

Furthermore, his father Zheng was the adopted son of Li Tan (李旦), whose success as a merchant and community leader in Manila’s Chinese community was unacceptable to the Spanish overlords.

So unacceptable that it led to the first massacre of the Chinese in the Philippines in 1603, which left 23,000 to 24,000 dead, brutally decimating the community.

The Spaniards resented Li Tan’s wealth, his immense property holdings.

Li Tan, according to Sterling Seagrave’s Lord of the Rim, the Invisible Empire of the Overseas Chinese, was “head of the great Amoy maritime trade network for 30 years.

Among Western ship captains he was called Captain Andrea Ditties, because anywhere you went from Surabaya to Nagasaki, if you wanted to buy needles and thread or other little necessities of life, you could find those ditties in one of the general stores run by Li Tan’s syndicate. “Before 1600, Li Tan had been ‘Captain China’ of the 26,000-strong overseas Chinese community in Manila, mostly Hokkien from Amoy.”

Many Spaniards in the Philippines also owed him serious money.

As a form of debt rescheduling, they provoked a quarrel that led to Li Tan’s arrest and sentencing to the galleys. They seized all his property in the islands, including more than 40,000 gold bars rumored to be only a small part of a huge mountain of gold and silver ingots he had hidden.

Seagrave writes, “The arrest of Li Tan and seizure of his properties outraged the Hokkien community in Manila. Li Tan was the head of their kongsi — a kongsi that had been in existence for more than a thousand years. The gold mountain belonged to all of them. “In Peking, Ming eunuchs stayed well informed about this dispute. In 1603, a group of imperial household eunuchs went to Manila to search for the rest of Li Tan’s ‘gold mountain.’ The arrival of these exotic creatures, dressed like dancing lampshades, alarmed the rustic Spaniards. They panicked and massacred 24,000 of the 26,000 Chinese in Manila. “Li Tan had other gold mountains stashed in Amoy and Japan, so after his escape from the Spanish galleys in 1607, he moved his headquarters to Hirado and Nagasaki, where he resumed his role as chairman of the Chinese Seas.”

Li Tan was from Quanzhou of Fujian who became rich through marine trading among Japan, China and Southeast Asia. He was one of the most important Chinese in Japan then.

Koxinga’s father, Zheng Zhi Long, joined Li Tan in Japan and gained Li Tan’s trust to the point that he became the magnate’s “adopted son.” He inherited most of Li Tan’s fortune.

Thus, through his father’s ninong, we find yet another link between Koxinga and the Philippines.

More importantly, the threat of Koxinga in 1662 also triggered the third massacre of the Chinese in the Philippines that left about 2,000 dead.

The Spanish authority feared that the local Chinese will support the invasion of Koxinga.

It was also during this period that Governor General De Lara ordered that canons be placed atop the Intramuros wall and aimed at the Parian where the Manila Chinese resided.

To sum it up, two of the six massacres of the Chinese in the Philippines were directly or indirectly related to Koxinga.

Today, Koxinga is worshipped as a god in coastal China especially Fujian and Taiwan, and around Southeast Asia. There is a temple dedicated to Koxinga and his mother in Tainan.

During the Japanese occupation of Taiwan, he is honored as a link between the two cultures because of his mother.

Even in popular culture today, Koxinga, under his own name Zheng Cheng Gong, is one of 32 historical figures who appear as special characters in the video game Romance of the Three Kingdoms XI.

A man of history. Was he pirate or hero? Friend or foe?

You decide.

First published in Tulay Fortnightly, May 18-June 14, 2010 issue.