First published in Tulay Monthly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 1, no. 11 (April 16, 1989): 4.

Philippine-Chinese relations has, in spite of some strains, lasted through the centuries. It began in pre-Hispanic times when the traders sailed the south seas and bartered Chinese silk and other wares with the native Filipinos.

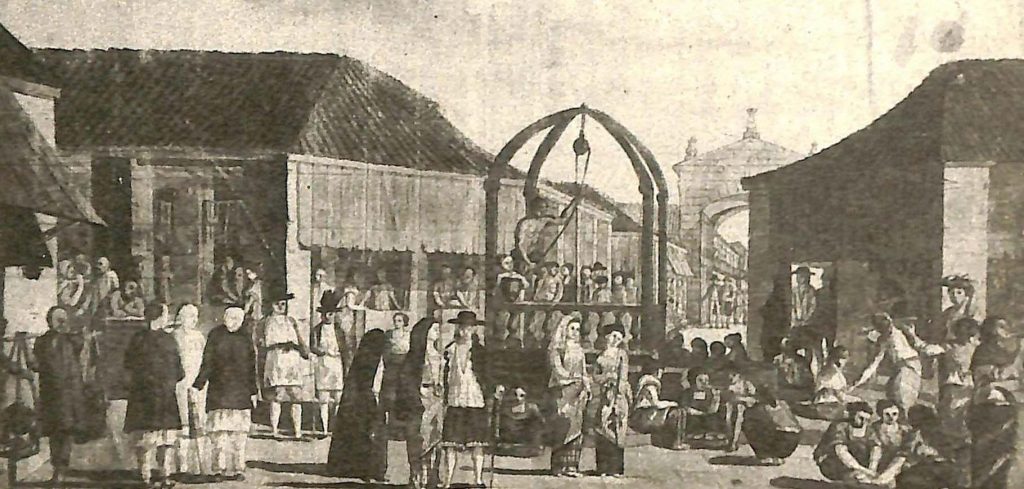

Their numbers rapidly increased when the Spaniards colonized the country because they served as the backbone of the colonial economy. They were not only traders and retail merchants, but also agriculturists, gardeners, physicians, barbers, sculptors, weavers, painters, bankers, masons, metal workers, fishermen, shoemakers and laborers.

Manila was dependent on the Chinese for almost all its trade and services. At the same time, the Chinese junks bringing in precious Oriental wares constituted the foundation of the galleon trade with Mexico and fixed the course of the colony’s economic life for over two centuries.

There were times however when the Spanish authorities, fearful of their rising numbers, and their tendency to dominate the trade and industries of the country, pursued a policy of restriction and discrimination against them. When such policy failed, they adopted severe measures of mass expulsion and wholesale massacres to stem the tide of Chinese immigration.

The attempts of the Spanish authorities to keep down the number of Chinese immigrants in the country were not quite successful as some very resourceful Chinese traders managed to establish themselves in remote towns and barrios.

These businessmen in some remote barrios of Mindanao were often looked upon as old relations and addressed as “iyo” (uncle).

During the latter part of Spanish rule, many Chinese set up small factories in larger communities employing Filipino helpers who later learned the trade. The town baker, apothecary, or grocer was always a Chinaman.

In the sugar-producing provinces the Chinese maintained packing plants. In abaca-producing regions, they even owned the plantations which they rented out to Filipino farmers.

In the Bicol regions, eastern Visayas and northern Mindanao, there was a wide range in the status and wealth of Chinese abaca traders.

Chinese involvement in the tobacco industry was indirect in that they manufactured low-grade cigarettes or cigars and established small sari-sari stores in very remote barrios.

All throughout the Spanish regime, the Chinese remained on the islands, living harmoniously with the Filipinos and contributing their strength and business know-how to Philippine progress and welfare.

By and large, it can be said that the centuries of Phi1ippine-China relations have been of mutual benefit to both Filipinos and Chinese. The Philippines has afforded China a market for her products and a second homeland for her enterprising nationals.

On the other hand, China has enriched Filipino culture and civilization and contributed immensely to the economic development of the Philippines.