First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 24, no. 7 (September 6-19, 2011): 8-10

In recent months, history-conscious members of Cebu’s Tsinoy community have grouped together to try and put up the Sugbu Heritage Center. It is to be similar to the Kaisa Heritage Center in Intramuros, Manila, established by nongovernment organization Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran Inc, as a lasting repository of the historical and cultural legacy of the ethnic Chinese on all aspects of Philippine life and in all events that shaped the Philippines as a nation.

To support the Cebu efforts, Kaisa tried to find some of the sources of information on the Chinese in Cebu.

A significant contribution to the Chinese Cebuano studies was the research by Associate Prof. Gyo Miyabara of the Global Collaboration Center of Osaka University in Osaka, with the help of Filipino sociologist and photographer Ito Jimenez.

The article, “Soil to be Repatriated: An Aspect of the Biopolitics of Chinese in the Philippines,” was drawn from an anthropological survey by the authors on tombstones in Cebu cemeteries and funeral notices in newspapers.

It was published in the volume edited by Yuko Mio, Cultural Encounters between People of Chinese Origin and Local People: Case Studies from the Philippines and Vietnam (Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, 2007).

The articles in the volume were presented at a workshop on “Indigenization, Creolization, Sinicization of the Ethnic Chinese in Vietnam and the Philippines” held on Oct. 28-29, 2006 at the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka.

Some of the study’s salient information related to Cebu are highlighted here. A few comparisons are made with the same research on tombstones of the Chinese in cemeteries all over the country.

A total of 39,479 photographs of tombstones in Chinese cemeteries from Aparri to Jolo were taken in 1992 to 1993 by Kaisa, together with the National Historical Institute in Manila and Taiwan’s Institute of Modern History of the Academia Sinica.

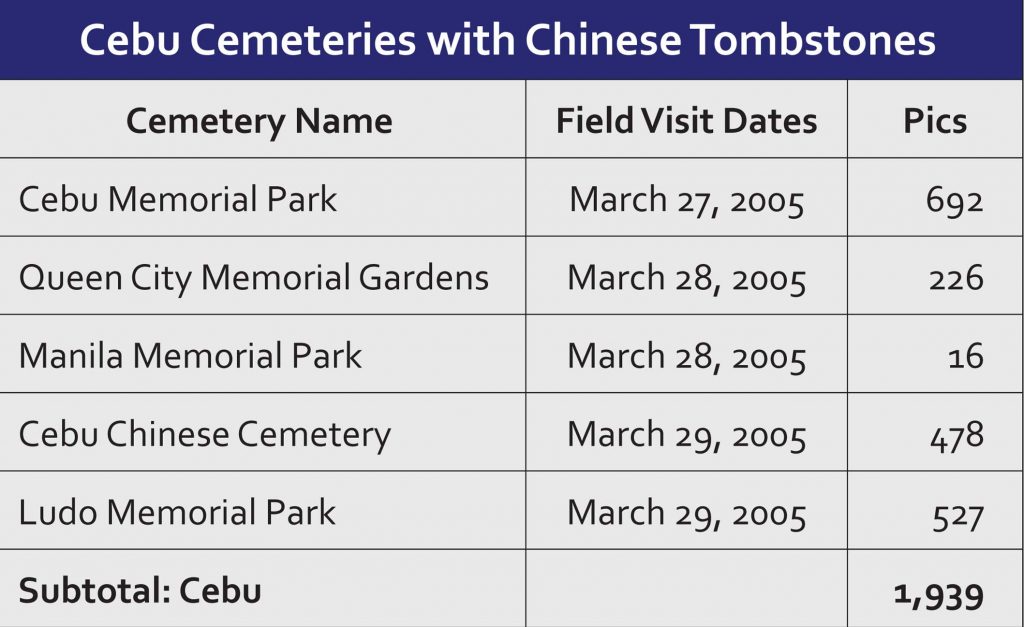

Chinese cemeteries surveyed in Cebu were the Cebu Memorial Park, Queen City Memorial Gardens, Manila Memorial Park, Cebu Chinese Cemetery and Ludo Memorial Park. A total of 1,939 photographs were taken from these graveyards.

Chinese family names

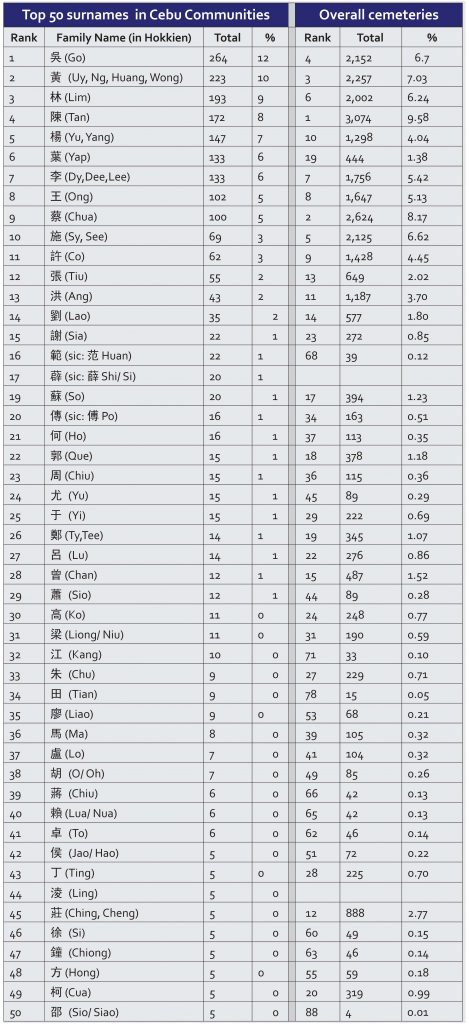

Data from tombstones show that in Cebu, the surname Go ranks No. 1 with 12 percent or 264 graves having that surname.

Overall across the country, however, the surname Go ranks fourth with 6.7 percent or 2,152 graves.

The surname Tan, with 9.58 percent or 3,074 graves, ranks No. 1 in the overall survey but is only No. 4 in Cebu. Ong (王)has the same rank (No. 8) both for Cebu and overall surveys. The biggest difference is shown in the surname Ching/Cheng (莊) which ranks No. 45 in Cebu but No. 12 in Manila.

It is not surprising that Go is the most prominent surname in Cebu. Tsinoy taipan John Gokongwei Jr.’s family patriarch, Pedro Gotiaoco, settled in Cebu.

Other prominent Cebu Go’s include the Gotao, Go Ching Hai, Gotianuy, Gotianun families.

Hometowns of origin

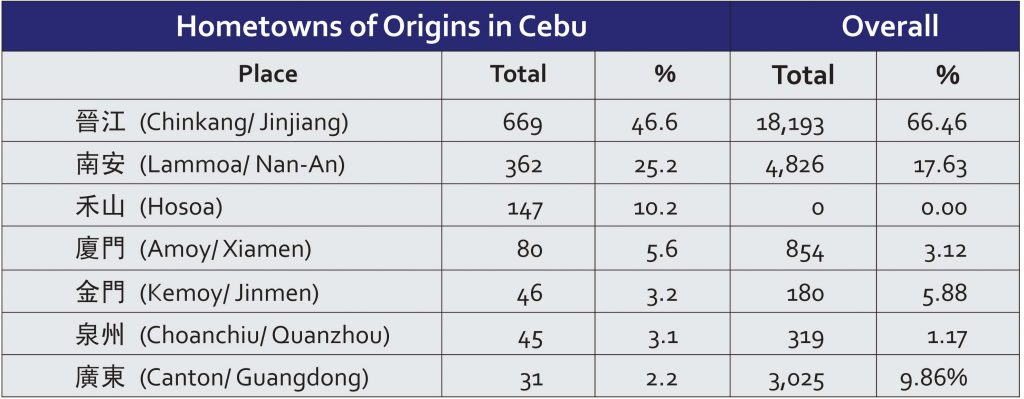

The hometowns of origin of Chinese Cebuanos resemble those in the overall survey. Almost half of Tsinoy Cebuanos came from Jinjiang, a fourth from Nan-an and three pecent from Quanzhou. The overall figures showed more than half from Jinjiang, a fifth from Nan-an and 1.17 percent from Quanzhou.

Jinjiang used to be under the political administration of Quanzhou. Both Jinjiang and Quanzhou are now cities.

The Cebu survey has Hosoa (禾山) which is part of Xiamen.

Intermarriages

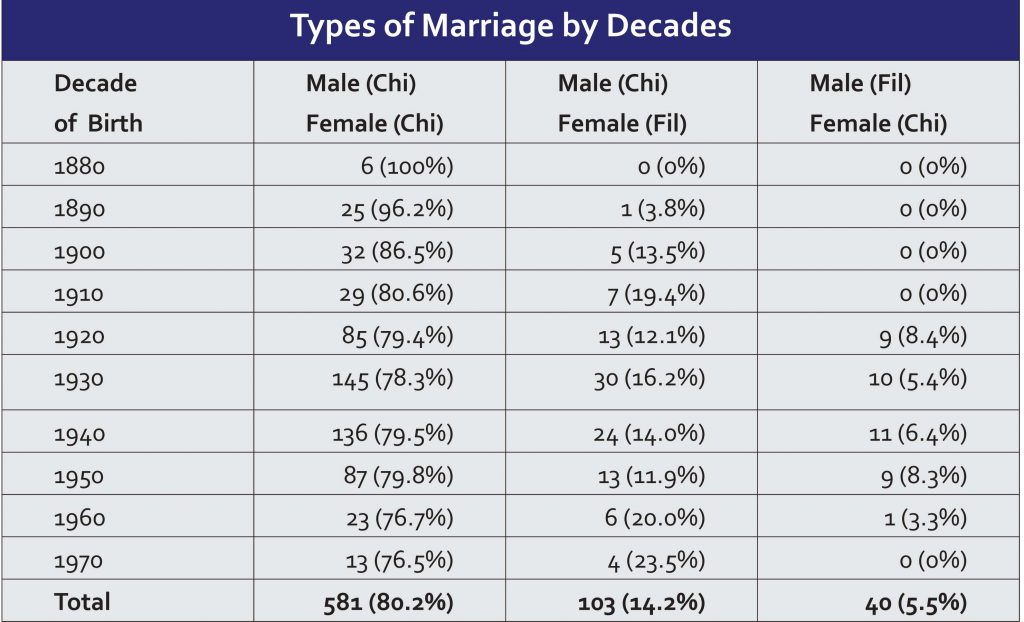

Statistics on marriage status showed very little intermarriages in the last two decades of the 19th century and first decade of the 20th century.

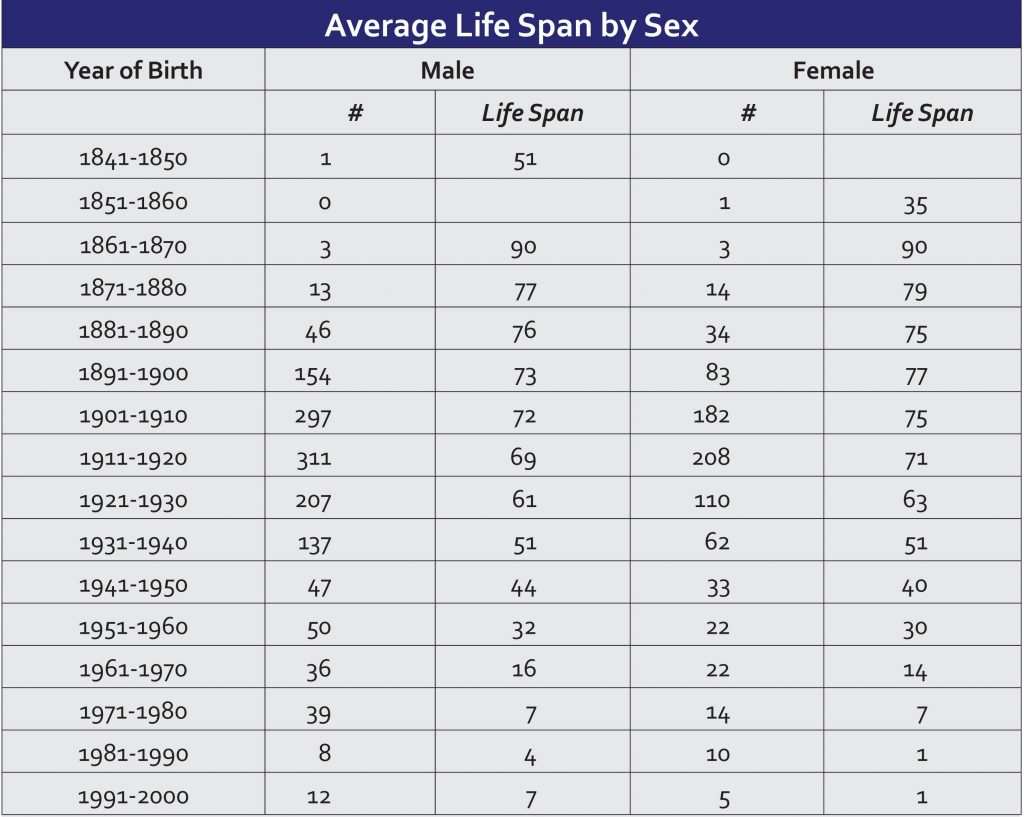

Average life span and sex ratio

The earliest burial in Cebu was recorded in 1897. The deceased was born in 1847, meaning he died at age 50. The sex ratio in 1894 was very lopsided: 122 males to one female in Manila; 1060 males to one female in the provinces (Doeppers 1986:384).

This apparently evened out over the years.

The Philippines is home

All the information above, garnered from the study of Miyabara and Jimenez, give interesting insights on the background of the early Chinese immigrants.

Perhaps, among the significant data given are those of the number of burials through the years. There were very little burials of the Chinese recorded from 1890s to before 1930s.

Part of the reason could be the destruction of the graves before World War II. But another important reason is that most of the ethnic Chinese in the Philippines before the war were sojourners or huaqiao (華橋): they were only temporarily sojourning in the Philippines. Hence, the bodies of the deceased were repatriated to China.

Today, their identities have mostly evolved to become ethnic Chinese or huaren (華人) if not Filipinos of Chinese descent of huayi (華裔).

This evolution highlights the transformation of identities of early immigrants to the Philippines from sojourners to settlers to people whose roots are now deep in Philippine soil and whose bonds are now completely with the Filipino people.