I have a short memory. This is why memorabilia, such as old photographs, are so important to me. They help me recall yesteryears, however faint the memory has become. Without them I am lost.

This story is about one search that took so long, traversed so many of my other-relative finder quests and even became a catalyst of several other unrelated family reunions.

One of the households my sister visited was that of my cousin Zeng Nana (曾娜娜). She lives in a high-rise condominium in the center of Quanzhou City, Fujian province.

One of her neighbors was a distant cousin of ours: Li Liubin (李柳彬). He asked to meet my sister and was invited to the reunion. He gave Christine 23 old photos.

Li Liubin grew up without parents and was raised by his maternal grandparents. Most of the photos were sent from the Philippines, from the family of his maternal grandfather Li Haojie (李豪傑) who had traveled to these shores to support his half-Filipina wife Zeng Wenjuan (曾蚊娟) and Li Liubin.

After several months of corresponding via email with Li Liubin, we finally clarified the identities of some of the people in the photos and through these individual’s relationships the photos can be categorized into four groups.

We do not know why Li Liubin gave these photos. Perhaps it was for safekeeping, or to help find the people in them. They must have their own tales to tell, tales that would be singular threads among millions from an era gone by.

Yet, these threads of life helped weave a tapestry that shows how it was in those days and for a moment gives life to those almost forgotten days.

Grandpa an overseas worker

These photos have been previously featured in two separate stories in Tulay: Relative Finder stories, “The missing tomb” (Nov. 6-19, 2012) and “Stories that qiaopi tells” (Oct. 8-21, 2013).

This set of photos can be further divided into two subsets. The first group is of Zeng Wenjuan.

Photos in the second subset are uniformly bigger and look more recent.

They depict Li Haojie’s funeral at Manila’s Chinese Cemetery. These photos had been helpful in tracing his tomb and confirming relations to people in Catarman, Northern Samar through some precious qiaopi letters the Samar family had kept safe.

Tomb sweepers

After the discovery of Li Haojie’s abandoned tomb, I took on – by default – the responsibility of looking after it: he was a distant relative, and there is no one else to do it.

It was during this time that I was introduced to the Qingming festival or tomb-sweeping day, an event Chinese all over the world celebrate around April 4-6.

It was also on one of my visits that I became acquainted with Jerickson, a tomb sweeper who lived in and around the Manila Chinese Cemetery. He became crucial in helping identify people in the second set of photos.

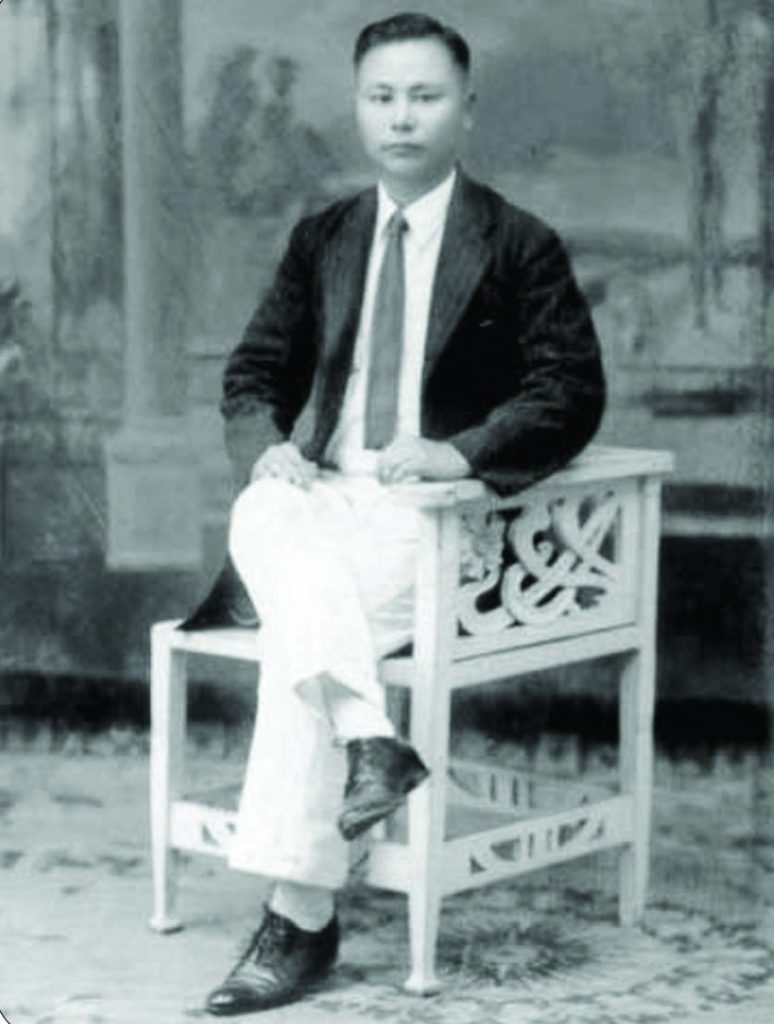

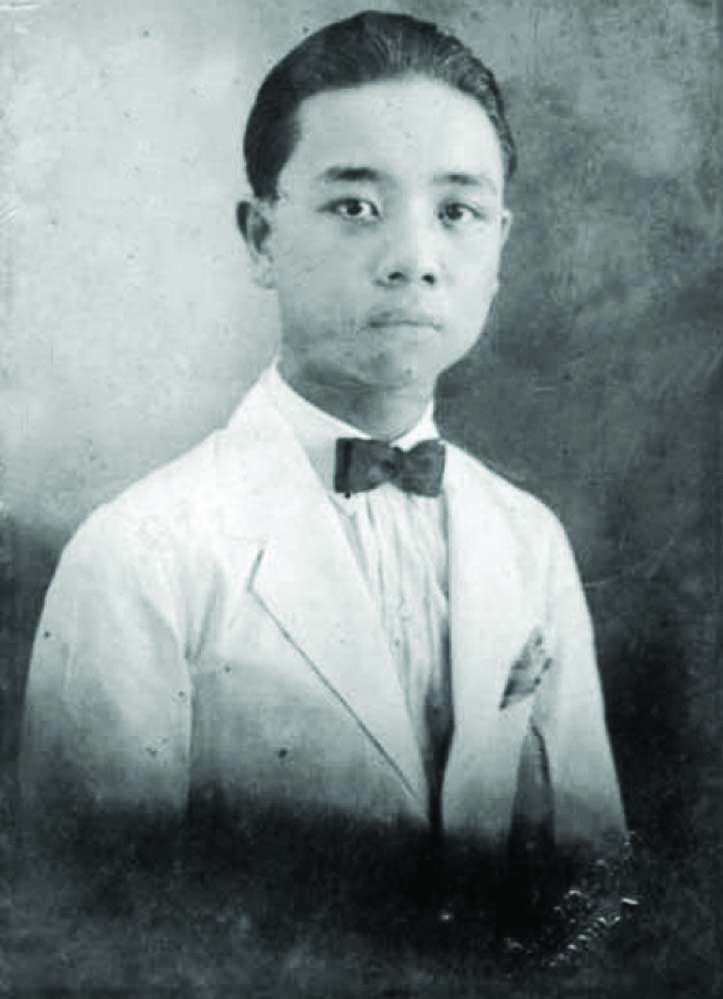

This set has three pictures, probably taken during the 1910s or 1920s. It shows an obviously wealthy family, probably based in Manila since all the watermarks point to studios in the city during that era.

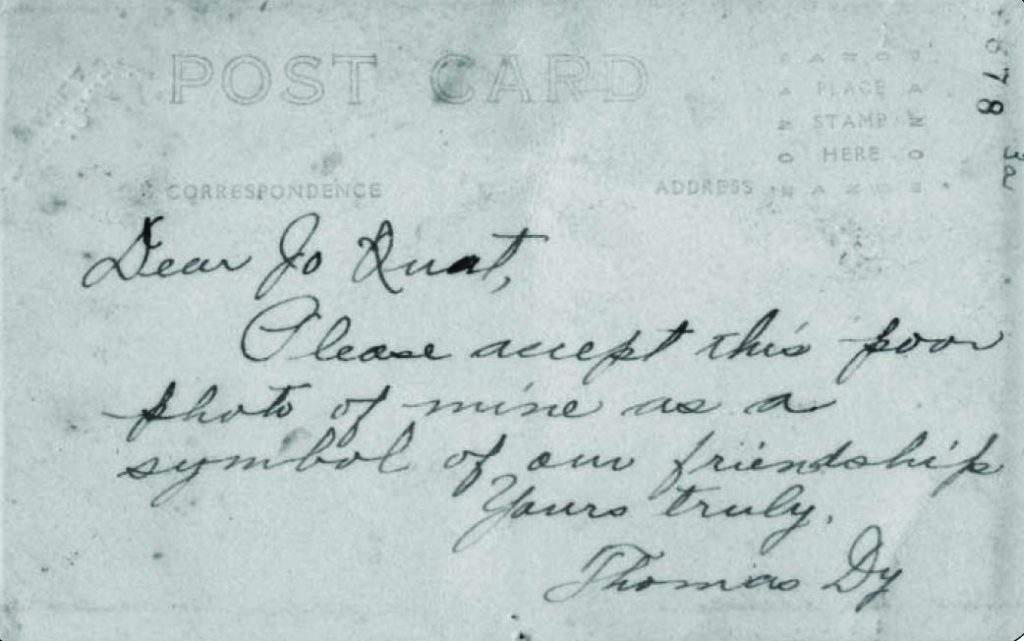

I tried to look for these photos by contacting the studios. But I found that all have long since shut down. The only other indication was one photo with a dedication at the back noting the name of the owner as Thomas Dy.

When cousin Zeng Nana visited the Philippines in 2010, she asked to visit the tomb of Li Liubin’s grandfather. It was an important request from her father.

Preparing for the visit, I contacted Jerickson to help us clean up Li Haojie’s tomb. During my cousin’s visit, the cleaner arrived at the tomb site riding a pedicab.

With him was an old sickly lady, Angelita Magracia, the former caretaker of Li Haojie’s tomb.

Magracia’s father was one of those hired to build the tomb. Father and daughter took care of the tomb for several decades and were paid by a certain Mrs. Sun Tay. She also took care of the tomb of Sun Tay’s ancestors on Lim Ong Road.

However, in recent decades, relatives no longer visited the tomb. The payments stopped. So the Magracias stopped taking care of it.

Before parting ways I obtained an address from Magracia’s surprisingly excellent memory of the family who paid for the tomb and its upkeep.

I visited the address in Pasay City and met Felix Dy (李純厚) who is in his 70s. He lives with his wife in a very old mansion surrounded by high walls.

Aside from the old mansion, there were many dogs and a 1970s vintage car that looked unused.

Dy immediately confirmed that the photos are of his family. In the old photo (#1), the man standing on the left was his father Vicente Dy Ping (李明平) and the children his older brothers. He was not yet born when the picture was taken.

Li Haojie was his father’s cousin, I was told, and they all came from Fuqiao county near Quanzhou. He also confirmed that the photo with English dedication (#2 and #3) was that of his uncle Tomas (spelled Thomas in the photo). It seemed that the person to whom the photo was dedicated was in fact Li Haojie (Dy Hokiat in Hokkien and spelled as Jo Quat in the dedication).

But he could not recall the name of his grandmother, the matriarch in the large family portrait. His only recollection of his grandmother is that of her funeral, when she was brought in a casket carried by an intricately designed horse-drawn carriage.

His grandfather was Dy Kwi Tong but he does not remember the Chinese characters.

The person who knows more of his family history and the rest of the photos was his sister, Sun Tay.

Unfortunately, she is bedridden and may not be able to give any information.

I gave Dy copies of the old photos. He was happy to have them. I too was happy: I have once again put a name – and some details – to people in the old photos and, even with the most minute detail, some stories of people in the old photos.

Hairstyle

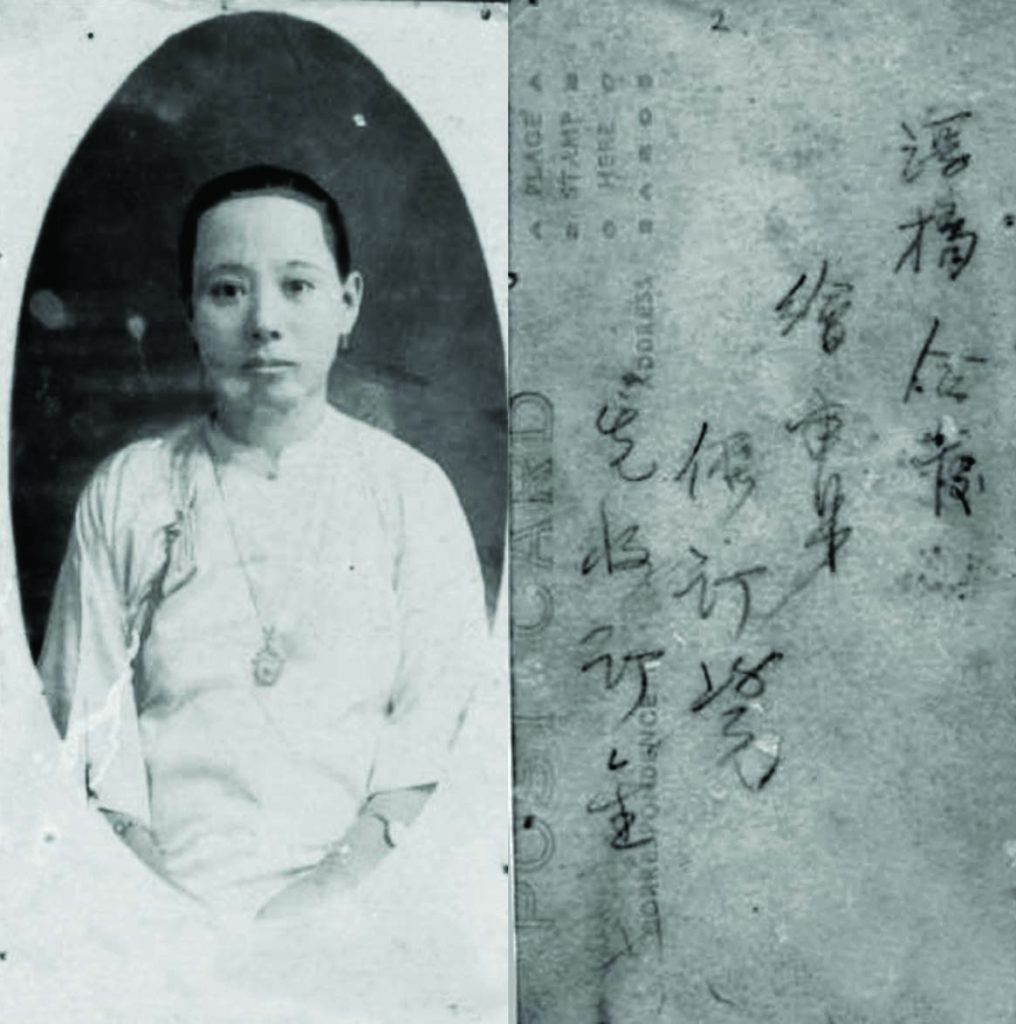

Another set of photos shows a woman with a very unusual hairstyle (#6), one which I have not seen in any of the old photographs. She was Dy Hiuku or Li Xianggu in Mandarin (李香菇), sister-in-law of Li Liubin’s grandmother Zeng Wenjuan (#7).

They both had bound feet and may have belonged to wealthy families.

Zeng Wenjuan was half-Filipina and had very Filipina features yet she stayed in China, I mused. Li Xianggu, on the other hand, was very Chinese in her features but migrated with her husband to the Philippines. The two women may have been very close. This set of photos had Li Xianggu in four of five shots.

The third set of photos was taken in Calbayog City, an hour’s drive from my hometown, Catarman, Northern Samar. Even though Calbayog is close to Catarman, this remains a quest to this day and is perhaps the most difficult search I have had so far.

According to Li Liubin, these photos are of his grand-aunt’s family (Li Haojie’s sister). Li Xianggu married a man from the same branch of my clan, the Chans (Zeng 曾), who was from the same village as my grandfather: Eni Village (下輦村 or 禦輦村) in Jinjiang City, Fujian. Chan’s name remains unknown although one of the sons was said to be named Zeng Wenpin or Zeng Wenbin (Chan Bonpin 曾文彬 or 品).

According to the Chan-Cu Family Association, if we refer to the generation poem of the Longshan branch (see “Relative Finder: Generation poem of the Longshan Chans,” Tulay, Jan. 20, 2015 issue), Li Xianggu’s husband could have been named Zeng Ren (specific name unknown) since the fathers of those of the Bon (Wen 文) generation use Din (Ren 仁 or 人) as the generation name. This is what his name could have been if his parents remained true to using the poem.

As for Li Xianggu, we do not know when and where she was born. But we do know when and where she might have died.

One photo is what is called a Recuerdos de Patay (#11). In the old days the dead was not embalmed. After death decomposition immediately sets. The deceased had to be photographed and swiftly buried.

Usually, the deceased in the picture is laid out to appear just asleep or resting while local family members surround him or her. Distant relatives get to see the deceased’s last moments before burial. Perhaps this is why Li Liubin had the photograph: the grandparents in faraway China would have seen grand-aunt Li Xianggu’s burial pose.

I went twice to Calbayog in search of Li Xianggu and her descendants. The first time was with my mother Nimfa Chan-de la Cruz and her friend Maria So-Luzon. After asking around the city, we scoured the city’s two cemeteries, the public cemetery and a private cemetery owned by the Chinese community.

We waded through weeds and abandoned graves under the heat of the midday sun seeking old Chinese tomb markers. We were finally led by a local to a third and more ancient looking cemetery located unassumingly deep inside a very populated and congested hillside barangay.

It is Calbayog’s old Chinese cemetery.

Deeper inside the cemetery, in an area that looked abandoned for decades, are about two dozen blackened pre-World War II Chinese upright headstones. But I did not find her grave among them.

The search for Li Xianggu’s descendants has led me to Baguio, to an old man named Chan Bon Pin. I eventually met Chan Bon Pin’s son in Manila but he said his grandmother did not have bound feet so they are not the family I was looking for. Like determining the meaning of her bizarre hairstyle, the search for Li Xianggu’s descendants remains an unresolved question.

The unclassified

While the search for Li Xianggu’s descendants is still unresolved, this final set of two photographs is as mysterious as the darkness of night! While the other photos have in some way an identifier, these remaining pictures hold no clue on who the people in them are or what their relationships are to the Li family. Even Li Liubin did not know who they were and how his family got the photos.

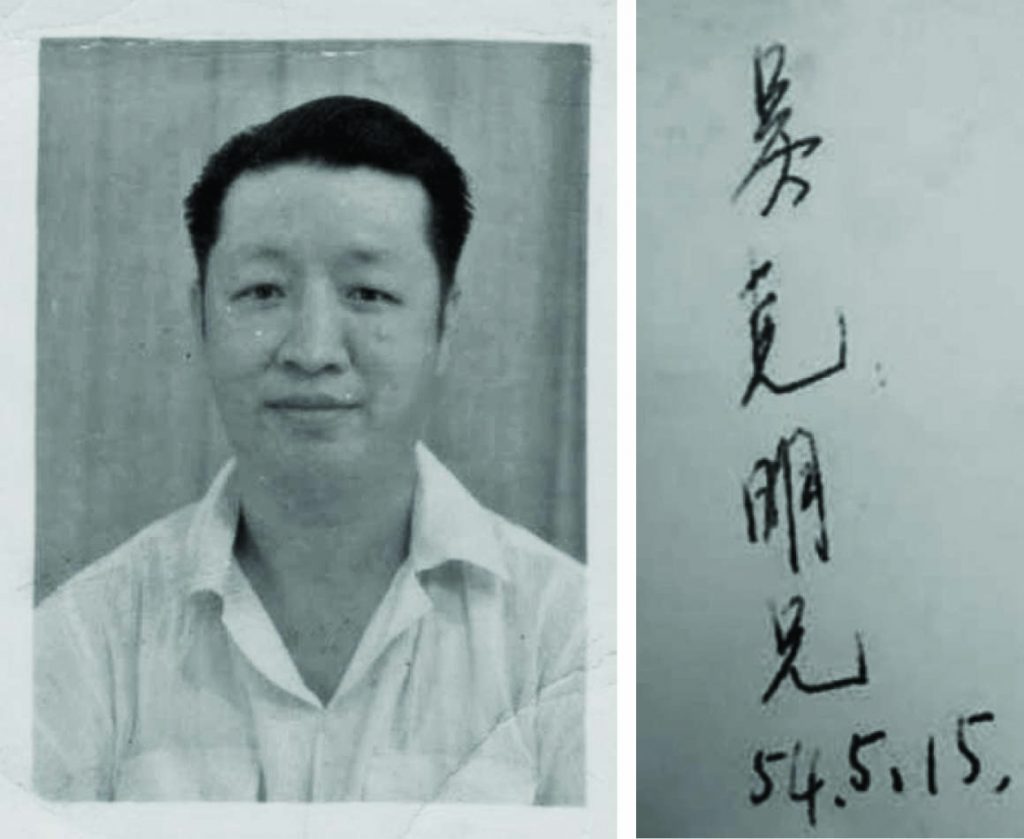

The first one is a small ID-sized photograph (#12) of a person named Mr. Go or Wu Ke Ming

(吳克明). This photo could have been taken for an official document. I visited the Go family association near Ongpin Street in Manila and was told there was no member named Wu Ke Ming.

Another one is of a woman and child (#10). Based on the woman’s hairstyle and dress, the photo may have been taken in the 1930s in the Philippines. Her dark complexion suggests she is Filipina, probably married to a Chinese man and mother of the Chinese-looking boy.

If you do recognize these people, please let us know who they are and share their stories. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 28, no. 4 (July 21-August 3, 2015): 8-10.