Family weddings are a wonderful time for family reunions and for exchanging gifts.

My relatives from overseas flew in this month with suitcases bulging with gifts. In turn, I was ready with my own gifts to give out.

Those who appreciated Chinese art received a hardbound copy of the book His Legacy Our Heritage: Professor Chen Bing Sun (陳明勳).

One recipient was a student in his art studio nearly 40 years ago. Another had a Chinese painting of a galloping horse (not by Chen) prominently displayed at home. Chen’s passion and calling was Chinese painting, his focus: horses.

“My dad paints horses in just three minutes… However, it took him 30 years of practice to be able to do it,” says his son and businessman Henry Chen on Facebook.

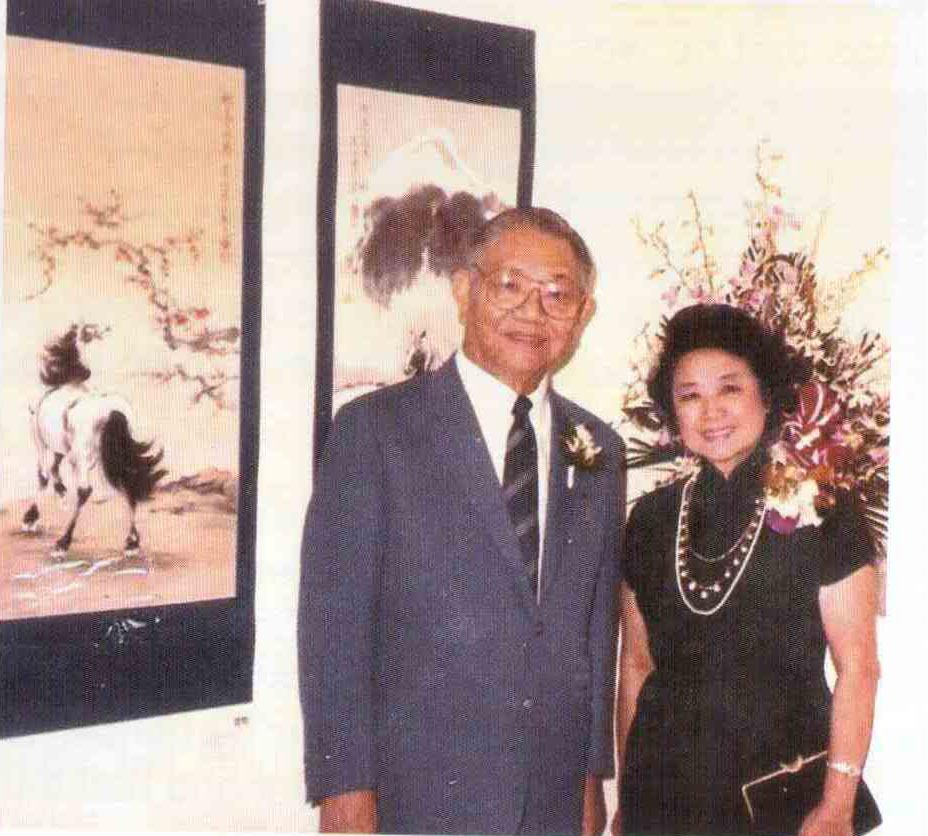

Henry, wife Monica and sister Florence Co were in Manila last November 2013 – Chen’s 25th death anniversary – for a special exhibit of the painter’s works at the Cultural Center of the Philippines. He would have been 100 then.

The two siblings, now living in the United States, recall how their father – dubbed the father of Chinese brush painting in the Philippines – spent time at the old Sta. Ana racetrack in Manila, just watching the horses stand, trot or gallop on the grounds, then fly furiously around the race course.

His paintings of horses are highly prized by Philippine art collectors. At the memorial exhibit’s opening night, family friend Alfredo Ching shared that one of Chen’s great works, 馬到成功, with 100 horses galloping up the slope of a great mountain, painted in 1985 – still graces the library in his home.

“It depicts the power of horses,” he says.

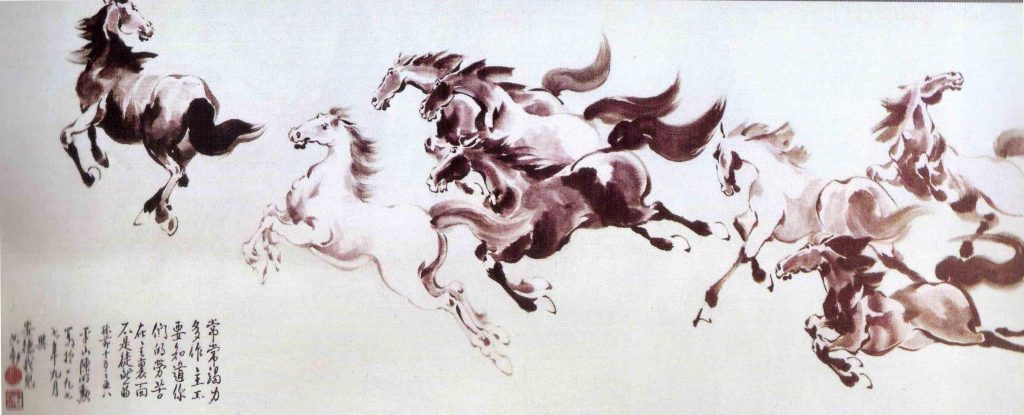

Indeed, horses are a main staple in Chen’s collection, some of which shows the artist’s humor. Henry recalls one with eight horses galloping, titled “Dedicated to Edward my son,” done September 1977. Edward is Henry’s older brother.

“See that one?” Henry points to the last horse in the herd, rearing and looking back, while the others raced forward behind a white mare which, in turn, followed a stallion.

The herd represents the Chen family. The stallion and mare are his parents, he says. The last horse is the family maverick: himself, the family non-conformist.

Chen’s repertoire includes a wide range of subjects.

In the Ching’s family room hangs a mural “黃山安徽.” The image is so real “you feel you are standing on the mountain,” Ching says. Another painting of peonies shows “good elegance.”

Traditional Chinese painting usually is accompanied by the artist’s calligraphy to the side. Chen’s work has both poetry and calligraphy, says Ching.

Deeply religious after he became Protestant, Chen wrote Biblical texts on his paintings.

When a collector asked him to remove the text on one of his paintings, Chen declined.

He also sang in the church choir, was a church deacon, and tithed regularly, giving more than the conventional 10 percent.

“At his first exhibit at the CCP (in 1977), he sold a lot of his paintings. It was the first time we saw so much money,” Henry recalls. “We never had much, but we had enough.

Papa put aside one-third and said, ‘This is for the Lord.’ ”

On his death bed, two days before he succumbed to cancer, Chen woke up, lucid, and asked for the title of a property the family owned in Fairview, Quezon City. He wanted to donate that to a Chinese church on T. Pinpin Street in Manila’s Binondo district.

“That left an impact on us, knowing the last thing he did was for the Lord,” he said.

Yet, Chen did not leave his family unprovided for.

Knowing his days were numbered by the malignant tumor, Chen worked feverishly, producing painting after painting. Their values were bound to rise after he passed on, ensuring his family’s financial needs would be met.

“He painted a lot to provide for my mom,” daughter Co recalls.

In 2010, the family discovered some 16 paintings still stored in a suitcase belonging to their deceased mother Annie Woo Chen. Since then, nine more have been sold; seven remain in the family.

Chen’s paintings are treasured by their owners. Occasionally, he gifted newlyweds with one of his original paintings.

His choice of subjects is diverse.

When a friend’s daughter married in 1984, he gave her a painting of two swans on a still pond. The choice of swans was symbolic: they pair up, are monogamous, their bonds lasting a lifetime.

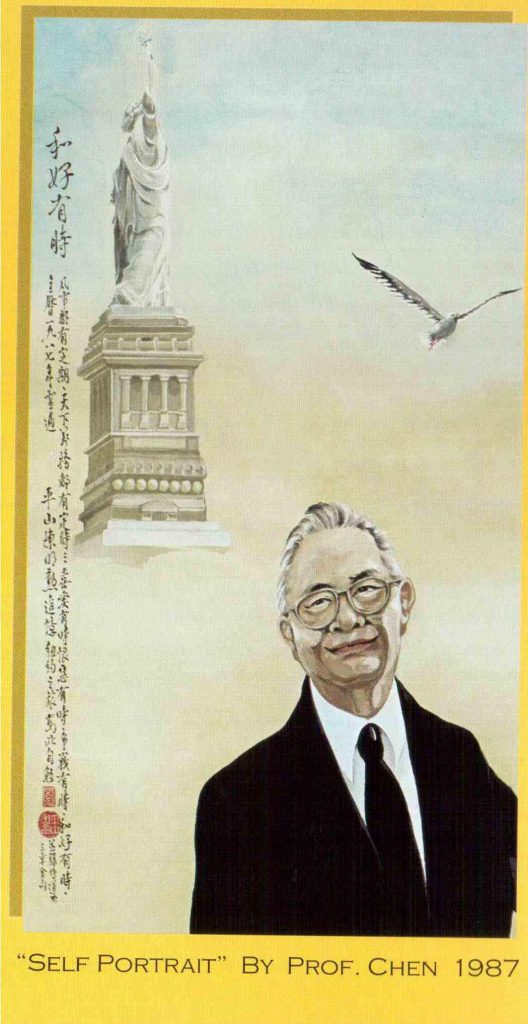

In a self portrait done 1987, he painted himself in his trademark dark suit, dark tie and white shirt, and in the background the American Statue of Liberty and a seagull in flight. It was a painting that used traditional Chinese brush techniques depicting untraditional subjects.

His suit betrayed his innermost predisposition.

“My father is a creature of habit,” laughs Co. “His shirts are all whites. His coats are grey, black or blue. He loves to wear suits. But he will wear a barong if it is warm.”

Co has a lot of good memories of her father and constantly thanks God for him.

Chen was very organized, structured and disciplined.

“He even organizes his bills,” Co remembers. “On Friday nights he counts his money, arranges the bills by denomination. If there are creases, he irons them, then puts them in his wallet.”

“He was a strict guy,” says Co, who used to help him at his art studio at the Manila Hotel. When she entered second grade, Chen would wake her up at five a.m. for prayers. This continued until she went to Bible college.

Breakfast followed prayers: simple, predictable meals of congee with century egg or mahu (肉脯 pork floss), or oatmeal with milk, or a fried egg.

“The meal had to be at a set time, so I had to wake up early to help my mom.” Then he was at work in his studio before 7 a.m.

On the odd occasion when this schedule deviates, “he is rattled and grumpy all day,” she recalls. After work each day, Chen would call to say what he wanted for supper before heading home. A lot of the meal preparation fell on Co, the obedient child. She prepared the meal when she came home from school, under her mother’s supervision.

“He didn’t want to tire my mama,” she said. “He loved her so much.”

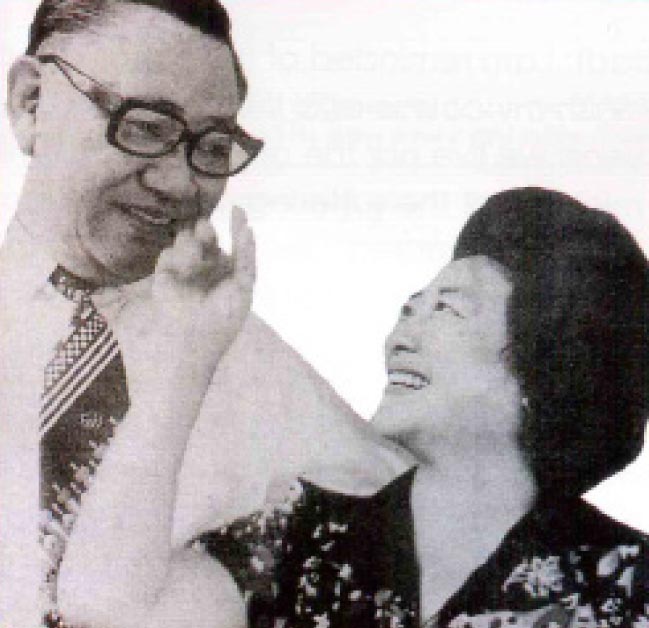

Wife Annie (吳靜娟 Wu Jingjuan) taught voice after she retired from an acting and singing career. Her stage name was Ow Yang Fei Ing (歐陽飛鶯), and to this day, she is remembered for her role in the Chinese musical film, “Eagle Flying Among the Masses (鷹飛人間),” and her hit song “Shangri-La (香格里拉).”

The two came to Manila in 1947. Chen, the manager of the Shanghai Artists Troupe, had negotiated the group’s Philippine tour. Annie was the leading actress and soprano and at the height of her career. After the visit, the troupe returned to China, but the two stayed on.

In Manila, Chen did not lack for things to do. He was a designer, poet, journalist, sculptor, stage director and painter. He did anti-communist cartoons for the local Chinese press, and was the Philippine correspondent for the Taiwan press.

He was Nationalist Taiwan’s chief delegate to a UNESCO convention in 1960. He was also the first overseas Chinese to win from Taiwan recognition in 1968 for meritorious service in education and art, Henry says.

As well, Chen and wife Annie were very involved at the then Grace Christian High School in Manila, and later in its new Quezon City campus. Annie taught music and religion. Chen provided support for the school administrators and the pastor at Grace Christian Church. He helped design the school publications and worked with stage sets and directed school musical plays.

In 1974, Chen worked with Tsinoy composer Huang Chen Mou (黃楨茂) to produce a cantata “Song of Wisdom (智慧之歌)” consisting of six songs.

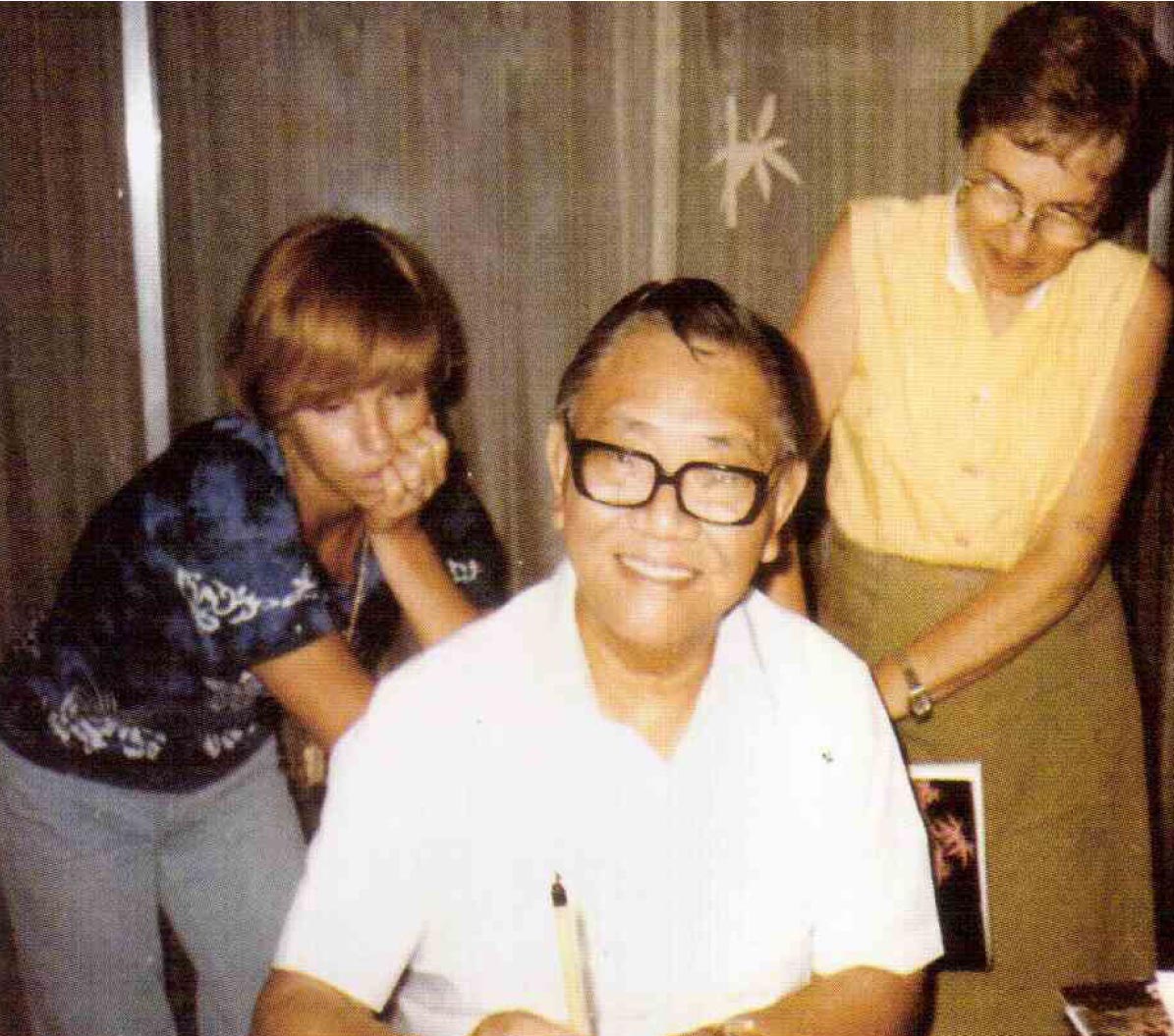

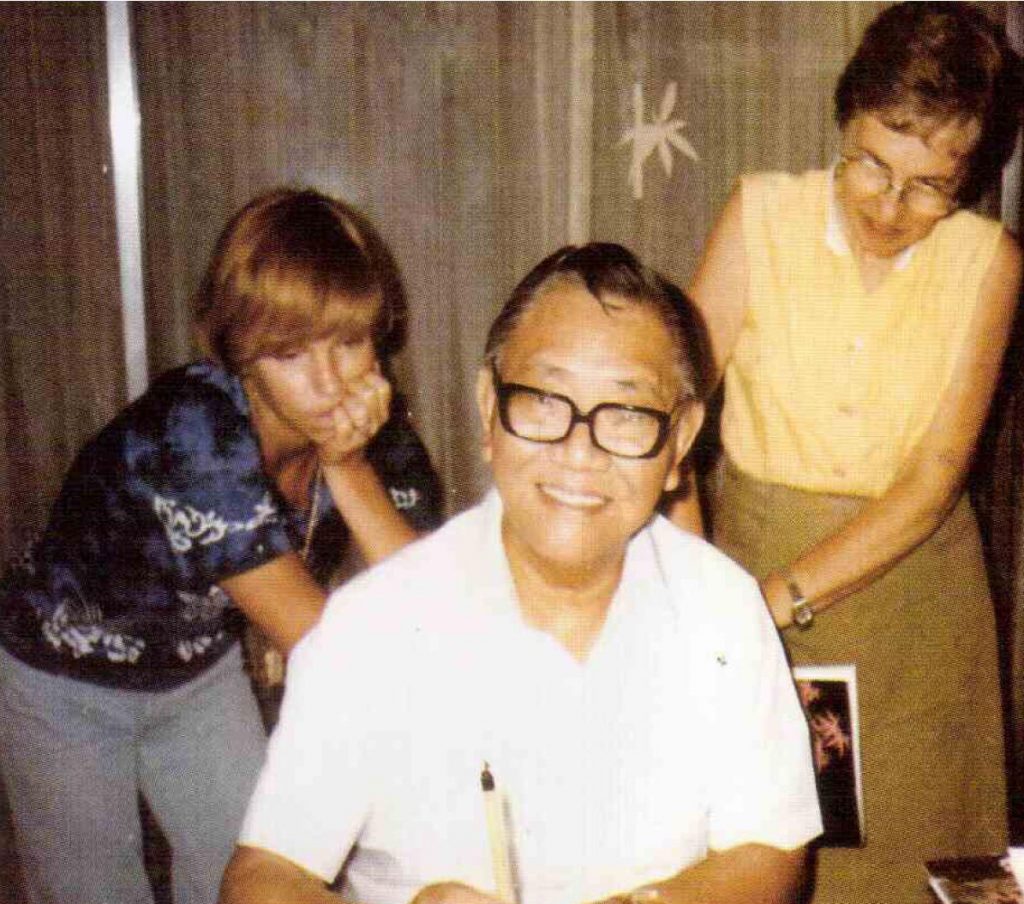

He and his wife also started the Chinese Artists’ Guild at the Manila Hotel. Chen took in students of all nationalities – Chinese, Filipinos and many expatriates – and for three decades, taught them the traditional art of Chinese brush painting.

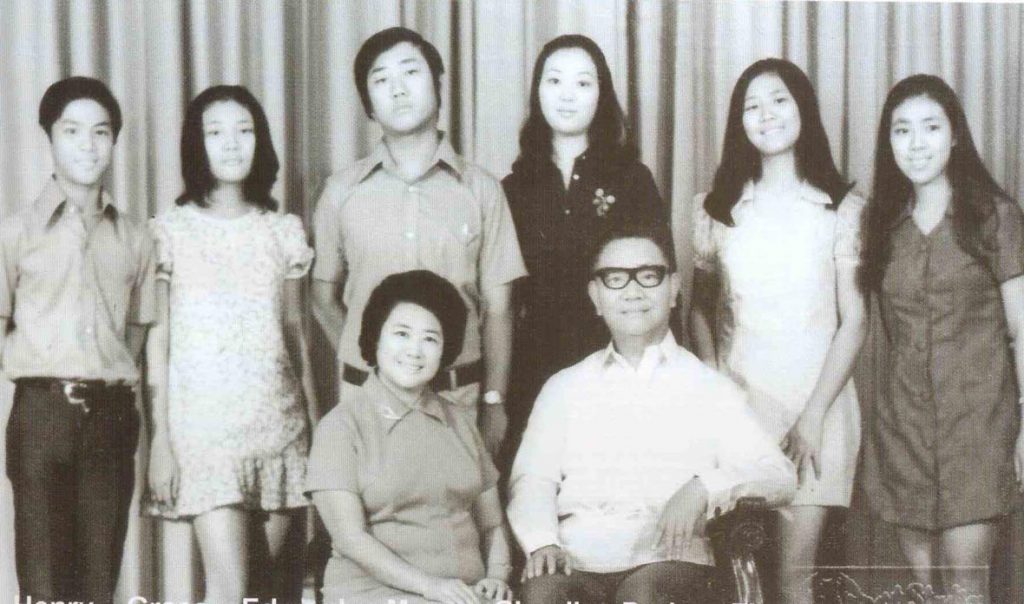

The Chen children did not follow their father’s path. Chen, a perfectionist, initially tried to teach art to his children, but his many criticisms discouraged them from following his footsteps.

The late Angela, the eldest, sang opera in Italy. The two boys are now in business. Co is involved in church music ministry. The other daughters work in various ministries, including evangelism in China.

Among all his children, he thought Co showed the most promise. Even after she had married, he urged her to go to his studio for training. “By then he was old and his cancer was advanced. We had two or three lessons, then he was confined.”

Co had been his favorite child, and he objected to her marriage because he had hoped she would dedicate her life to art. Yet when he saw she was determined to marry, he went to the police to check that his future son-in-law had no criminal record.

But to show his disappointment anyway, he did not go to the wedding. Her brother Henry gave her away.

As well, “he wouldn’t give me a painting,” she says. Each of her siblings had received a painting from him when they married. Instead, “My mom bought me one of his paintings. She could do that because she handled his sales.”

With the professor’s often unyielding views on life, it was Annie’s disposition, “happy, sweet, that balances him,” Co says.

“Papa’s paintings sold because of mama’s charms.”

A child protégée, Chen was trained since childhood by his father, an artist as well.

“His father would put a cup on top of his fist which held the brush. He was disciplining Papa, it is hard to hold that position (and not let the cup fall). “Papa cried when he was spanked because he spilled the cup.”

But the discipline paid off. He placed first in written exams in elementary school, breezed through high school, and while still a teen, taught in university in Shanghai.

Chen’s art school exposure included schools in Hangzhou (1930) and Shanghai (1936), Henry says.

Once, Chen and his father had both entered a painting competition, each unaware the other had done so.

“Papa won. My grandfather got mad,” Co says.

In his lifetime, Chen held solo exhibits in Manila, Hawaii, New York, California, Delaware, Washington DC and Nagoya, Japan.

He never exhibited in China or Taiwan, Henry notes, because he usually painted traditional Chinese subjects: mountains, flowers, bamboo, and of course, horses. There are many who do that in China and Taiwan.

For his part, Ching says Chen’s greatest contribution is more than producing beautiful art. It is bringing the artistic and cultural heritage of his country to the world. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 27, nos. 1-2 (June 17-July 7, 2014): 26-27.