Jose Rizal is alive and well in Hong Kong! If you know where to look, you can find our national hero in this bustling metropolis. All you need is a good pair of shoes and a city map. Then seek out the historical markers.

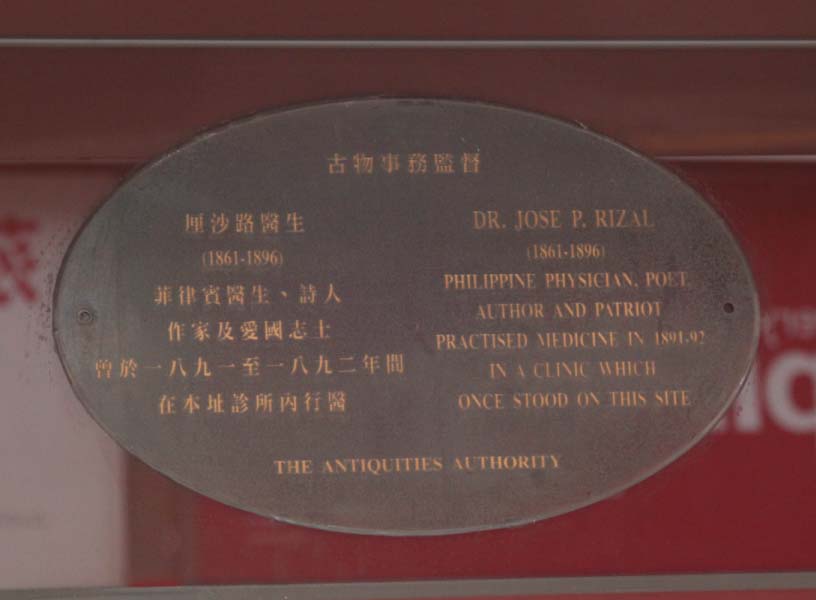

There are three historical markers scattered across Hong Kong island. These are produced by the Hong Kong Antiquities Board in honor of Rizal and other Filipino patriots who lived there during the 1890s. Together, they formed what I call the Filipinas Heritage Trail.

Rizal and other Filipino patriots went to Hong Kong, according to Hong Kong writer and historian, Jason Wordie, because this former British colony has a long history of sheltering dissidents from all over Asia.

Sun Yat-sen, Zhou Enlai and even Ho Chi Minh took refuge here at one time or another.

Rizal went to Hong Kong after leaving London in October 1891. He lived there with his family after the Dominican friars dispossessed them of their farm. They settled on a steep hillside street in Hong Kong known as Rednaxela Terrace. The street acquired its name because the Chinese sign painter spelled the intended name “Alexander” backward, typical of Chinese writing from right to left.

Rednaxela Terrace during Rizal’s time was also home to Hong Kong’s Portuguese community. Perhaps the family was comfortable with the neighborhood.

Wordie wrote how the Spanish community in the Philippines and the Portuguese community in Macao had many close connections due to Catholicism.

In fact, “Some immigrant Filipinos blended in with the creole Macanese communities, first in Macau and later in Hong Kong and the Treaty Ports. Many local Portuguese families have some Filipino ancestors.”

In Wordie’s book, Streets: Exploring Hong Kong Island, he described Rednaxela Terrace and the nearby terraced streets as providing …‘cheek-by-jowl’ terraced accommodation early last century for the less well-off members of Hong Kong’s local Portuguese community. Mostly lacking private sanitation, this was where the ‘clerical’ class made their homes, a convenient walking distance to their places of employment in the business district further down the hillside.”

But despite its humble housing, the Portuguese community was invaluable to Hong Kong’s business community because its members spoke English and Cantonese. Many of them were hired by leading British firms, banks and shipping companies.

On Rednaxela Terrace, the marker honoring the site where Rizal’s one-time home is just below the street sign. It was unveiled Dec. 30, 2004.

“It was here that [Rizal’s brother] Paciano translated ‘Noli Me Tangere’,” said guest speaker history professor and writer Ambeth Ocampo at the ceremony. “The manuscript was corrected by Rizal himself and could be the definitive translation, but was unfortunately lost. It was here that Rizal began a third novel after El Filibusterismo. He completed only a few chapters, but it is significant because he tried, but failed, to write in the language of his country—Tagalog—instead of Spanish.”

Rizal never viewed his stay in Rednaxela Terrace as long term. In fact he planned to move his family and other dispossessed Filipino farmers to Sandakan, Borneo. According to writer Luis Francia, “…the British North Borneo Charter Company was amendable to having the prospective immigrants settle on 5,000 acres of land, rent-free for three years, the financial costs involved and the almost certain refusal of the Spanish colonial government to allow such a move in the end doomed Rizal’s endeavor to have the country come to him rather than he to the country.”

If the Rizal family were to return to Rednaxela Terrace today, they probably would not recognize it. The street and surrounding neighborhood have since been cleaned up and transformed into an upmarket area with cafés, galleries and pubs.

In fact, residents there no longer struggle up and down the steep sloping streets as they did in Rizal’s time. It is now connected to the business district down the hillside by an extensive escalator system, reputedly the longest one in the world.

To reach the next historical marker, I decided to do as Rizal did and follow his daily commute down the steep streets. (This was also because the elevator goes down the slope only 6 a.m. to 10 a.m.)

My plan was to walk down Shelley Street heading toward Cochrane Street and turn right into Stanley Street. When I reached the first corner at Caine Road I noticed signs directing toward the Sun Yat-sen Museum. It certainly roused my curiosity, but I decided to stay on course with the Filipinas Heritage Trail.

Later on I learned that Sun frequented the area when he was studying at the College of Medicine for Chinese. He was already in his final year as a medical student when Rizal and his family moved there. Did the two ever meet? Perhaps. I think it highly possible the two may have walked past each other along the terraced streets of Hong Kong.

Once I reached Stanley Street, I walked to its other end to reach D’Aguilar Street. It was at this corner that Rizal set up his ophthalmology practice in Hong Kong. The site has since been taken over by a commercial building called Century Square. In fact, if you are winded after walking down Shelly and Cochrane streets, you can take a break with a tall glass of iced latte here, because Rizal’s marker is underneath the window of a Starbucks coffee shop!

But it wasn’t always like that. When this marker was first unveiled in 1997, it was located on a much more prominent spot on the front of the building. But this is not an indication that Hong Kong folks are unaware or do not care about Rizal and his contribution to Philippine history. In fact all three historical markers were made possible under the term of former Home Affairs Secretary Patrick Ho, a well-known admirer of Rizal. And like Rizal, he is also an ophthalmologist with a clinic on D’Aguilar Street.

Despite his failure to treat his own mother’s eye successfully (because she disobeyed his order to leave the bandages on!) Rizal gained a good reputation as an ophthalmologist in Hong Kong. One patient, George Taufer, followed Rizal back to the Philippines just to have his eyes treated.

In this case, however, you can truly say that love is blind, or rather, Cupid is: accompanying Mr. Taufer to the Philippines was stepdaughter, Josephine Bracken, who later became Rizal’s fiancé.

With the opening of his clinic, you can probably say Rizal was one of the first overseas Filipino workers in Hong Kong.What I find interesting is that his former clinic is not far from where the Filipino expatriate community meets today. Located at the corner of Des Voeux Road and Pedder Street is the World-Wide House, which is home to various small shops selling Philippine-made products as well as firms handling remittances and offices of freight agents. As well, the Hong Kong branch of Filipino fastfood chain Jollibee is just next door.

On a Sunday, the place feels as just like the Cubao Metro Rail Transit station in Quezon City, rather than Hong Kong’s Mass Transit Railway Central station.

Rizal closed his clinic and returned to Manila July 1892 to meet his destiny.

The last marker on the Heritage Trail remembers another Filipino patriot, Dona Marcela Agoncillo, wife of a brilliant lawyer from Taal, Don Felipe Agoncillo. She followed her husband to Hong Kong after he fled in 1896 to escape arrest for taking part in revolutionary activities.

While in Hong Kong, the Agoncillos rented a house in what is now called Happy Valley. To get there I hopped on one of the old-fashioned tram cars that have served Hong Kong since 1904. It was headed for Happy Valley (or Pao Ma Ti to the locals). At the end of the line, I boarded the connecting tram and got off two stops later near the Cosmopolitan Hotel at Wong Nai Chung Road.

The Agoncillo home is nearby at 535 Morrison Hill Road. It was here that Don Felipe was reunited with his wife and family after a nearly two-year separation.

But why did they live on Morrison Hill? According to writer and historian Wordie, the area was largely paddy fields and mosquitos bred there. Being a fever prone area, rent there was probably cheaper than elsewhere in Hong Kong.

Emilio Aguinaldo eventually joined them after he went into exile following the signing of the treaty at Biak na bato. Don Felipe then served as Aguinaldo’s diplomat, after the Hong Kong Junta was formed.

Scholar Rolando Mactal noted revolutionaries crowded not only into the Agoncillo house but also into another house nearby. Both were rented for P50 per month. The houses became the center of the Emilio Aguinaldo’s government in exile. Anyone who moved elsewhere received a P12 monthly pension, hardly enough to pay the rent even in those days.

When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, American warships arrived in Hong Kong to refuel, then sailed for Manila in late April, where they won against the aging Spanish naval fleet.

When Aguinaldo heard the news he was eager to return to the Philippines. He met with the Agoncillos and requested them to sew a flag according to his design. He wanted the flag to be a symbol that would unite the country. When Dona Marcella received the request she recruited her eldest daughter, five-year-old Lorenza, and Delfina Herbosa de Natividad, Rizal’s niece by sister Lucia.

The three began sewing the flag May 12 and finished in five days. Aguinaldo brought the flag back with him to the Philippines May 17. After using the flag in three battles, Aguinaldo hoisted it at his home in Kawit, Cavite when he proclaimed the country’s independence. He later unfurled the same flag during the Malolos Congress when he presided over it.

A hundred years after Dona Marcela sewed the flag, Hong Kong’s Urban Council decided to unveil a plaque to commemorate the event. The marker is located inside Morrison Hill playground on the side facing Queen Elizabeth Stadium.

The playground however was not the site of the former Agoncillo house, which is actually a few meters away. The owner of the building refused to have the marker installed on his property. It was unveiled just in time for the country’s Centennial celebration.

Upon seeing the three historical markers, I had mixed emotions. I was happy and proud that our country’s history was honored by another territory. But I felt burdened as well. While we have achieved freedom from our colonizers, we are still struggling to win freedom from poverty and corruption. But if there is any lesson we can learn from Rizal and the other patriots, it is that each of us should do what needs to be done. It does not matter how small the task may seem or how big the sacrifice it may be.

A final note: I wanted to leave a small momento on each of the markers as offering to our country’s history. But I do not know if it is permitted to leave something behind like a small flag. But perhaps on my next visit to Hong Kong, I may take a chance and do just that. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 24, nos. 1-2 (June 14-July 4, 2011): 14-16.