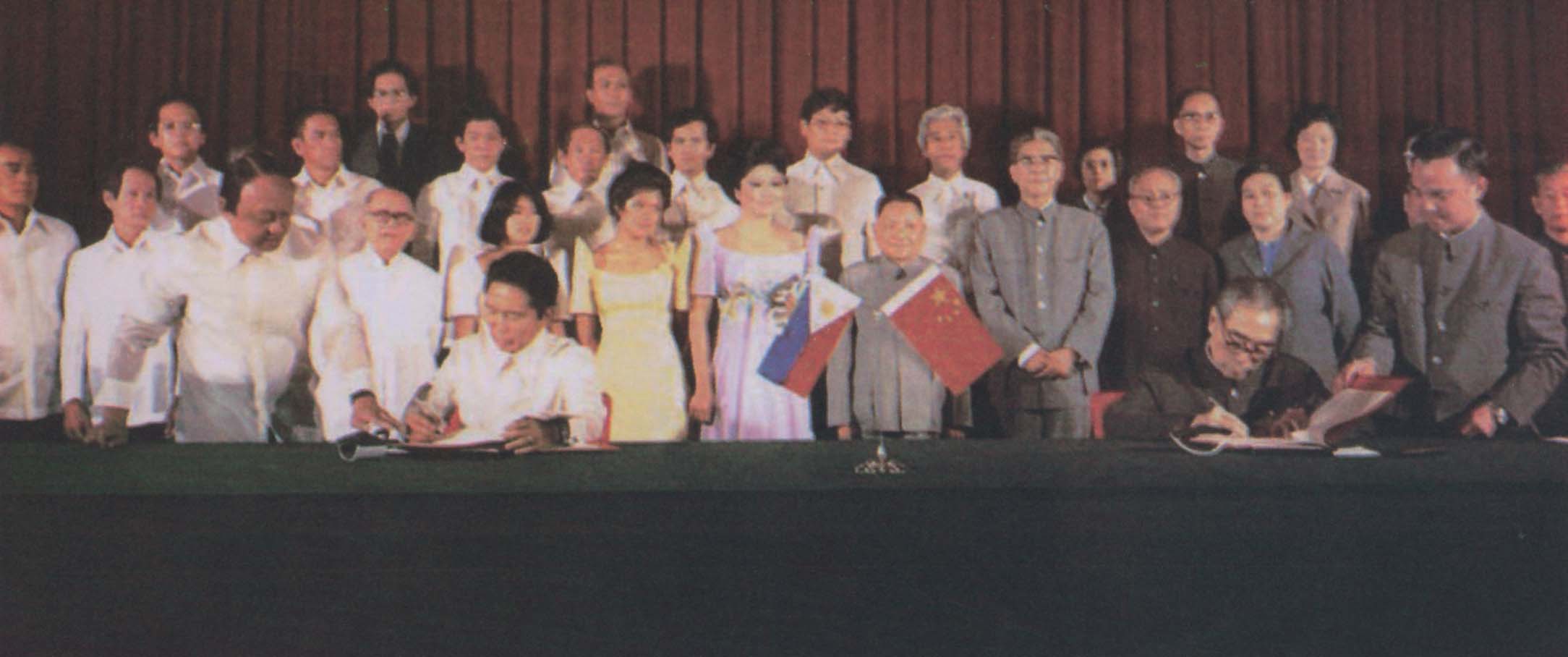

This year (2015), the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China commemorate 40 years of diplomatic relations. The joint communiqué was signed June 9, 1975 by Philippine President Ferdinand E. Marcos and China Premier Zhou Enlai.

The day is now celebrated as Philippines-China Friendship Day.

It underscores the centuries of friendship between the two countries, begun when traders made possible the exchange of goods and culture.

In the years after Philippine independence, our country was a strong bastion of Taiwan (read Kuomintang) influence.

Before Marcos declared martial law in 1972, two out of the three Chinese-language dailies were pro-Taiwan, Chinese schools were supervised by the Taiwan Ministry of Education. Chinese textbooks came mainly from Taiwan and Chinese teachers were graduates of Taiwan universities.

Chinese organizations were likewise largely pro-Taiwan. In fact, for two decades after diplomatic relations were established in 1975, many Chinese-Filipino community leaders refused to have anything to do with China and would often go abroad or out-of-town because they were uncomfortable meeting with visiting dignitaries from China.

Things change. Today, many Tsinoys do business with China and even the most conservative leaders have been to China. Local Tsinoy organizations have likewise touched bases with China.

At the celebration of China’s 60th National Day (October 2009, its foundation day), an avid pro-Taiwan Tsinoy leader was invited to the event. More than 1,000 guests from around the world were witnesses to the spectacular hospitality and organization by their Chinese hosts.

Yet, that leader still only had complaints about China. His attitude is a hold out from earlier days, and by then belonged to the minority.

Paving the road

The road towards normalizing relations with the People’s Republic of China was not an easy one. It was fraught with difficulties, mistrust and suspicions on both sides.

China saw the Philippines as a lackey of the United States. Meanwhile, the Philippines feared China’s communist revolution and influence, especially after martial law was declared and the underground leftist insurgency flourished.

Careful but astute probing, prodding and manuevering behind the scenes helped bring about events that, in turn, led to the establishment of relations between the Philippines and China.

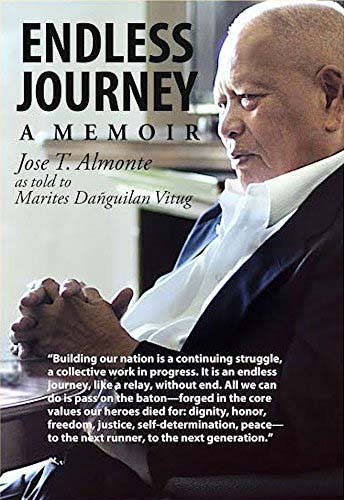

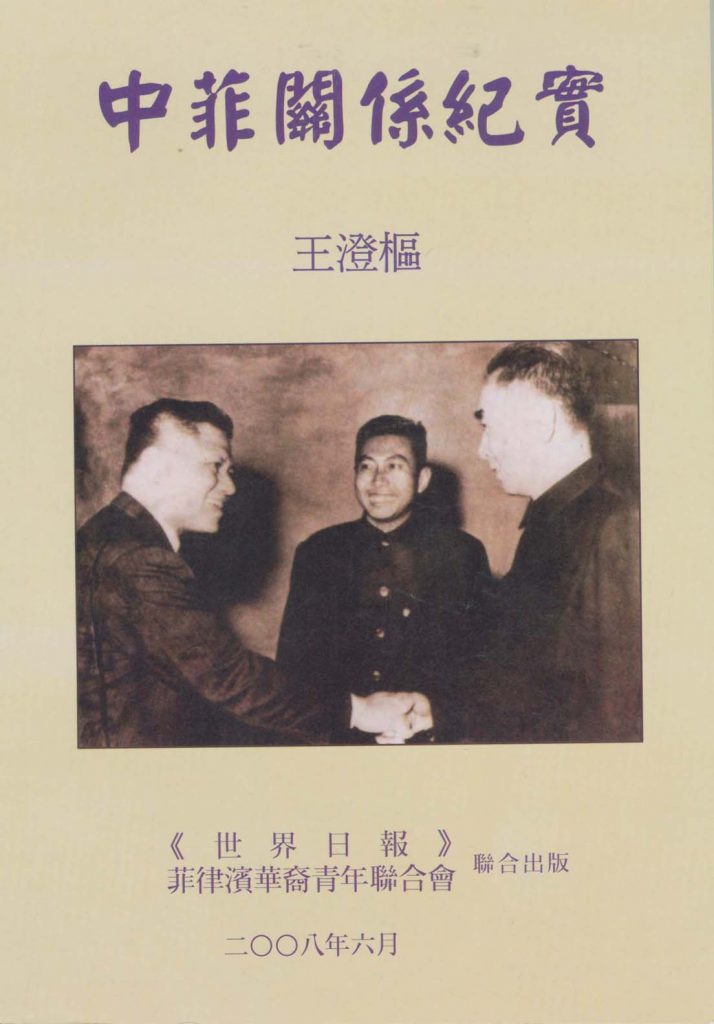

Stories and vignettes on the background footwork are revealed in two books.

One is in English: the recently released Endless Journey of Gen. Jose T. Almonte; the other is in Chinese, the 2008 monograph of Wang Chengshu (王澄樞), Witness Account of Philippines-China Relations (中菲關係紀實).

Almonte, 84, a graduate of the Philippine Military Academy, served as national security adviser of former President Fidel V. Ramos.

He was also deputy chief of staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, head of the Economic Intelligence and Investigation Bureau and head of strategic studies of the Philippine Center for Advanced Studies.

Wang was editor of the business and local news sections of Chinese-language daily, Fookien Times when he was based in Manila.

Upon his return to China, he served as member of the State Council’s Overseas Affairs Office desk in Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines and deputy chairman of the China-Friendship Association and President of the Returned Overseas Chinese Association.

He held various diplomatic posts and became Deputy Minister of the Education and Propaganda Division of the State Council.

Wang confirmed that visiting China after the 1949 liberation was taboo among Filipinos. The intrepid few who managed to secretly do so risked political reprisals or having their passports cancelled.

“It was a regrettable situation. The only way for Filipinos to understand China is to visit and see the situation for themselves,” he wrote.

The following description of events leading to 1975 are from Wang’s monograph.

“The first Filipinos who visited PRC were Manila Chronicle publisher Luis Mauricio and his reporter Gabriel Mañalac in 1955.

“The serialized reports of the visit created a sensation and opened Filipinos’ eyes about the new China.

“The Chinese Commercial News translated the articles into Chinese and its readers, hungry for news about their homeland, gobbled up the copies.”

In 1958, the first Filipino public official to visit PRC was Jesus Marcos Roces, vice mayor of Manila, upon the invitation of the Institute of Foreign Affairs (外交學會).

At the farewell dinner tendered by the host, Roces, a bit drunk, said: “I am anti-Communist. But, I cannot deny that China under communism is successful.”

Journalist Apolonio Batalla of Manila Bulletin who was with the delegation reported the same in his serialized reports about the visit.

In 1959, Fernando Gonzales, with the office of President Carlos P. Garcia, visited China upon the invitation of the Institute of Foreign Affairs. They were met by Vice Premier Chen Yi.

Before departure, Gonzales said: “Seeing it once is better than hearing about it a hundred times. I saw and heard new things about China and I will certainly encourage more Filipinos to visit.”

Gonzales kept that promise.

China suffered three years of economic difficulties (1960-1963) and suspended foreign visits.

In 1961, Tarlac Gov. Benigno Aquino Jr.’s request to be invited to visit China was denied.

In 1963, Asian, African and Latin American countries sent athletes to the Jakarta Games of the New Emerging Forces (新興力量運動會). The Philippines noted this. Though quite late in the day, we too decided to send a 20-member track and field team to participate.

At the last hour, two days before the games’ opening, China decided to send Wang (the author) as a companion and interpreter of the China delegation. One of his tasks was to engage the Philippine team. He met the head of the delegation, a Col. del Rosario, who was quite warm and forthcoming.

Wang asked why the Philippines did not send its famous basketball team. Del Rosario replied that the Jakarta GANEFO is not official in Olympics competition, but the Philippines did not want to be isolated from participating Asian neighbors. Hence, a token team was sent not to win but to observe and learn.

Wang suggested to Del Rosario that Chinese and Filipino athletes must have a get-together after the games. This was arranged and the teams met, had snacks and warmly chatted.

The Filipinos praised the Chinese athletes’ excellent performance at the games. The Chinese, in turn, invited their new friends to visit them in China. This was in fact the opening salvo of sports diplomacy.

In 1964, after a four-year hiatus, China was again ready to open its doors. Gonzales went to Hong Kong to meet with Chinese officials to broach the possibility of Filipinos visiting China, including four journalists who wanted to attend China’s 15th National Day celebration.

They were Manila Chronicle journalist Hercules Gallego, Renato Tayag of Manila Times, Tito Fernandez of Daily Mirror and photographer Leopold of Evening Post.

The guest list for the National Day celebration had been vetted and completed. This sudden request left Chinese officials in a quandary.

However, China was aware Philippine media reports about China had been largely negative. Officials were also informed that this group of media men had strong suspicions, doubts and distrust about China.

Given the last-minute request, it was a dilemma whether to invite them or not but eventually, the National Press Association of China tendered the invitation. It was a good opportunity to let them understand China better.

Knowing the background, the Chinese hosts allowed them greater leeway in their visits and they were given relative freedom of movement despite difficulties in security arrangements for them.

Zhou was supposed to meet them but due to National Day preparations, the meeting was canceled.

However, at the foundation day banquet, Zhou approached the group and asked them to relay his greetings to Filipino diplomat and statesman Carlos P. Romulo. They had met at the Asian-African Conference (萬隆會議) in Bandung, Indonesia in 1955.

They had exchanged gifts then. Romulo gave Zhou a piece of Philippine handicraft that was displayed among the state gifts at the People’s Hall of Congress.

The group serialized their reports for three days in three different newspapers. They reported extensively on matters of hygiene and sanitation in China.

Apparently, these reporters had a contest on who would sight the first fly or the most number of flies in China. They, therefore, enthused that they failed to encounter flies even in their “sneak attacks” or unplanned visits to communes; toilets, no matter how crude, were still more sanitary than those in Philippine rural areas.

Tayag, in particular, published in a book the collection of his articles. Because of their reports on “sneak attacks” and “naughty escapades” (altering the planned itinerary even if it created so much difficulties for factories and households they suddenly decided to barge into), their articles gained much more credibility and readers believed that they indeed saw the real China.

This had great impact on introducing the real China to Filipinos and counteracting the many negative reports fed by propaganda, possibly by pro-Taiwan and rightist elements.

Closely following the visit was the five-member group of Manila Times columnist Maximo Soliven. They were Feliciano Magno of Daily Mirror, Gabonton Santos of Philippine News Service, Johnny Dayang of Philippine Graphic and Ms. C. Malay.

Manila Times was the newspaper with the biggest circulation at that time. Its publisher, Chino Roces, came from a powerful and influential family. The PNS was the country’s lead news agency with reporters all over the country. Philippine Graphic was the leading magazine in the country. The group’s importance was seen in the dialogue with Zhou who defined China’s domestic and foreign policy to them.

As agreed upon, Soliven published the full text of Zhou’s talk. This had far-reaching and significant impact in letting Filipino readers know about China’s policies. He wrote more than 20 columns about his China visit.

Because he had visited the city previously, he was able to report on the huge contrast between the Shanghai of yesteryears and the new one. He told Wang that the English dictionary should remove the entry on Shanghai because the city by then no longer fit the definition.

Wang was likewise touched when Soliven said the two people he admired most was the late Franklin D. Roosvelt and the still hale and healthy Zhou.

His visit coincided with China’s successful test of its first atomic bomb. His first-hand scoop on the varied reactions of the Chinese from all sectors about the momentous event likewise created a sensation. His report about China’s last and retired emperor Pu Yi described how China educated and reformed the last emperor.

The group was brought to see the dance drama “The East is Red” which had just opened. Soliven said the performers deserve a gold plaque for the stellar performance.

“If there is a bamboo curtain, that curtain is not in China,” he concluded.

“Soliven was US-trained and his views and mine aften clash and the heated discussion often reached a stalemate. But such frank and open discussion helped in mutual understanding and promoting friendship.

“Soliven eventually became publisher of The Philippine Star. After 30 years, whenever I had a chance to visit Manila, he often invite me to eat. He died in 2006. I grieve for the loss of a dear friend,” Wang laments.

In 1965, Central Luzon Herald’s Pacifico De Guzman and Taliba’s Rolando Fadul met with Zhou. Fadul had previously submitted a question about Taiwan and Zhou used the opportunity to discuss the Taiwan situation. Fadul published in full Zhou’s position on Taiwan in Taliba, the largest circulating Filipino paper.

This was the first time the Taiwan question was raised and it had impact on the discussions toward establishment of diplomatic relations.

Starting from the opening of the State Council External Relations Office in 1958, Chinese leaders had started overtures towards countries which had no diplomatic relations with them (Philippines included).

In October 1965, after seven years of intensive preparations, the first radio program of China’s International Broadcasting Station in Filipino aired in Beijing, breaking the silence and news blockade about China. The daily news broadcast in Filipino had far-reaching impact in informing Filipinos about the situation in China.

In February 1966, Sen. Maria Kalaw Katigbak visited China upon the invitation of All China Women’s Federation (中華全國婦女聯合會). She was accompanied by Manila Chronicle columnist Carmen Guerrero Nakpil, a close friend of then-First Lady Imelda Marcos, and several others.

Katigbak was the highest elected public official to visit China since its establishment in 1949. She was also connected to the Philippines’ two biggest sugar and coconut families. To the Chinese, this signals the shifting of Marcos’ outlook towards China and gave great importance to the delegation.

Huang Changsui (黃長水), an old friend of Katigbak and now the deputy of the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council (國務院僑務辦公室), was appointed to guide the delegation.

In May 1966, Taliba columnist Amado Hernandez and Fadul were invited by the China Writers’ Association to attend the Asia-Africa Writers’ Conference. After the conference, they stayed on for more than two months to visit places in China.

China gave importance to these two guests. Hernandez was a former councilor in Manila’s city council, head of the Congress of Labor Organizations and was incarcerated several years for being pro-Communist.

His columns had influence. He published more than 60 articles on what he saw, heard and experienced. These helped readers understand China better and elicited great influence on how people viewed the supposedly closed society.

More influential Filipinos visited China from 1966-1967: Philippine Free Press publisher Teodoro Locsin, his wife and son; and J.V. Cruz and Adrian Cristobal (who became a Marcos confidante) who brought a group of Filipino journalists and a youth delegation.

Then in 1968, due to the Cultural Revolution, China’s State Council halted activities with the Philippines. In 1971, China was admitted to the United Nations and started thawing its frozen relations with the United States. Filipinos began prodding for the normalization of relations with China.

The Association for Philippines-China Understanding (菲中了解協會), with former Education Secretary Alejandro Roces as president, was organized to push for normalization.

In February 1972, Sen. Salvador Laurel was invited by the Institute of Foreign Affairs to visit. Accompanying him was Leyte Gov. Benjamin Romualdez who relayed Imelda’s request to visit China. This was denied and Imelda shrewdly headed a big delegation instead to China’s arch rival, Russia. This was confirmed in Almonte’s book.

In April 1972, APCU president Roces and his members were invited by China Friendship Association (對外友協) to visit.

The delegation included (former President) Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and many others who became influential members of (former President) Fidel V. Ramos’ cabinet: Gemma Cruz-Araneta, who became secretary of Tourism, Charito Planas, who became mayor of Quezon City, and Raul Goco, who became solicitor general.

After martial law was declared in 1972, official visits were halted for a year.

Basketball diplomacy

Sports had several times paved the road in Philippines-China relations. While it was well known that ping-pong diplomacy helped in US-China relations, little known was how basketball diplomacy helped in Philippines- China relations.

Zhou again played a crucial role in this matter.

Wang writes: “Spring of 1974, the bursting of spring colors and opening of peach and plum flowers seem to portend that Philippines-China relations will be opening a new chapter.”

The Filipino basketball delegation was invited to visit by the National Athletics Association. It was headed by envoy to the US, former Ambassador Eduardo Romualdez, Imelda’s cousin and former Finance secretary. His deputy heads were the University of the Philippines Asian Center’s dean Ruben Santos Cuyugan and Almonte, then a colonel and head of UP’s Strategic Studies Department.

Basketball was the Philippines’ national sport. The high-level delegation elicited China’s attention and the high regard accorded this group was in evidence when then Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping himself met with them.

Wang writes: “The third day after the delegation arrived, the real intent was revealed. After lunch, the third name on the guest list – Almonte – asked for a private meeting with their liaison officer.

“He revealed then that Marcos was ready to establish diplomatic relations with PRC. The first step was for China to invite Imelda to visit, and the second step was for Marcos himself to visit and establish diplomatic relations.

“Almonte revealed that his delegation was tasked to discuss these matters with PRC high officials.

“Upon hearing this news, Zhou told Deng (who was to meet with the delegation the next day as previously arranged) that the delegation should be informed that Zhou himself would also meet the group.

“Romualdez naturally was aware of the significance of Zhou’s seeing them. He relayed the request to invite Imelda to visit, an invitation which Zhou readily extended for anytime she deemed convenient.”

In May 1974, China’s basketball team reciprocated the Philippine team’s visit to China. Thus, the Chinese sports team became China’s first official delegation to the Philippines, opening the road toward normalizing relations.

September 1974, just before China’s 25th foundation day, Imelda, with a 100-member delegation, visited China.

They met Jiang Qing on the second day, who accompanied them for a one-day trip to Tianjin. Mao Zedong later met with key members of the delegation in Changsha, an unprecedented and very high-level move.

Imelda made a long-distance call to Marcos to report success. She suggested that Filipino officials who opposed diplomatic relations should visit China.

In his State of the Nation address in January 1975, Marcos announced his plans to establish relations with China.

The China Friendship Association tried to organize a delegation to visit the Philippines, using civilians’ gesture to further encourage Philippine officials to normalize relations.

However, a number of high Chinese officials doubted Marcos’ sincerity and denied the plan for visiting the Philippines.

Yet, in June 1975, Marcos and Imelda, with a huge delegation, made a state visit to China and met with Chairman Mao.

On June 9, 1975, the joint communiqué establishing diplomatic relations was signed after negotiating the long and difficult winding road to that historic event.

Wang’s account of China officials giving importance to the visit of the basketball delegation somewhat differs with Almonte’s.

Wang confirms the basketball diplomacy.

Almonte writes: “Outwardly, it was to play basketball but it was meant to be a diplomatic basketball to use the occasion to get in touch with Premier Chou En-lai and Chairman Mao Tse-tung and convey the message of Marcos that the Philippine government was seriously interested in opening diplomatic relations with China.”

Marcos thought that China may be insulted if Almonte heads the delegation since he was just a colonel. Hence, Romualdez was called from Washington to bring the delegation to China. Almonte revealed that Marcos gave him no instructions on how to relay his message.

Up to a day before their departure, Almonte reveals, there was still no meeting set with Zhou or Mao because Romualdez’s attempts to communicate with their offices were not entertained.

“…We lost the basketball game and are losing in diplomacy as well,” he writes.

As a maneuver to get that crucial meeting with Zhou, Almonte deliberately relayed a tall tale to the liaison officer that Marcos wanted China’s advice in his plan to replace the U.S. from their bases in the Philippines and let Russia in instead because of Russia’s increasing influence in the Asia Pacific.

The liaison officer got up to make a call and upon his return, he told Almonte that Zhou would meet him before they left for the airport.

This account directly contradicts Wang’s, who revealed that there was already a pre-arranged meeting with Deng. Almonte could have relayed the message to Deng about the diplomatic relations and there was no need to play a false card.

Almonte admits: “I learned later that they were thinking of meeting us toward the end of our visit.”

Informing them about Russia “added color and gave them the rationale for meeting us.”

Almonte recounted two stories that added color to the preparations for diplomatic relations.

“Mrs. Marcos’ visit (to China) in September 1974 showed the importance China gave to the Philippines. Premier Chou En-lai, who was recovering from heart ailment, received Mrs. Marcos in a hospital in Peking. News reports said they met for about an hour after which Chou En-lai walked down along the corridor with Mrs. Marcos and took her to her car.”

It was an “unprecedented compliment to a visitor who holds no official position and is only deputizing for her husband,” The Age reported. Before this, the premier had not seen any foreign visitors for two months.

Another story was about China’s gift to the Philippines.

“In early 1972, Peking hosted President Marcos’ brother-in-law, Leyte Gov. Benjamin Romualdez, for trade talks. A reciprocal Chinese mission came to the Philippines as well.

“During these bridge-building forays, a special Chinese delegation attended the New Year’s traditional call of the diplomatic corps on the President. They gave Marcos a most unexpected gift: fertilizer made from horse manure.

“Then, US Ambassador to the Philippines Henry Alfred Byroade (1969–1973) ribbed him: ‘Mr. President, in trying to deal with China, all you get is horse shit.’”

The executive secretary, Alejandro (Alex) Melchor Jr., was beside the president and heard this conversation. Marcos was upset. He wanted to know what the gift meant.

Melchor called up Almonte, who was fortunately at U.P.’s Asian Center at that time, to ask the symbolism behind the gift of horse shit.

Lily Ledesma, a UP assistant professor, showed Almonte The Crippled Tree, author Han Suyin’s historical account of China.

Horse manure fertilizer, for the Chinese, is the beginning of life. If you use it when planting, it germinates life. It creates life.

Almonte relayed the symbolism to Melchor and writes: “Marcos delivered an elegant and moving speech out of it. His point of view was: our friends, perhaps alluding to the US, usually give us material things, but the Chinese – they give us their soul. Given the US-China rivalry, Marcos’ response was admirable, coming as it did from a pawn in the Cold War.”

As we celebrate the 40th anniversary of Philippines-China relations, we should remember that China had always treated the Philippines with respect, friendship and assistance accorded a developing country.

Disputes over the South China Sea should not erase the solid foundations upon which the relations have been built.

At the same time, China should also respect that the Philippines will stand up for what is right within the limits set by international agreement like the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

In the meantime, both sides should cool off the issue and refrain from provocative pronouncements and undertakings.

Both sides should keep in mind modern formal diplomatic relations between the two countries began on amicable grounds. Disagreements should likewise be resolved with courtesy.

After all, friendship of the two nations began, not merely in the 1970s with the exchange of basketball teams, but centuries ago with the trade winds. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 28, no. 1-2 (June 16-July 6, 2015): 14-17.