My previous column on “Balagtas and Binondo” mentioned that Balagtas’ deep immersion in the volatile environment of Binondo reached a crucial stage during the violent October 1820 massacre. The event must have jolted the foundations of his personal convictions and impelled what could have been his political epiphany.

But what is the October 1820 massacre?

In the history of the Chinese in the Philippines, the 1820 Binondo massacre is usually referred to as the sixth Chinese massacre in the Philippines. In terms of the number of Chinese killed, this massacre was the smallest: 85 Chinese. But there were foreigners – 50 Europeans – killed as well.

The sixth Chinese massacre was the only one that occurred in Binondo, the previous five massacres having happened in the Parian. But the 1820 massacre is the least known and least mentioned in history, and seldom explained and narrated in detail.

We greatly appreciate that Fred Sevilla devoted eight pages of Chapter 7, “Manila’s Ferment and Social Unrest,” in his opus Poet of the People: Francisco Balagtas and the Roots of Filipino Nationalism to this incident. His account can be considered as the best and most comprehensive narration and analysis of the October 1820 Binondo massacre.

To understand what really happened, it is necessary to quote lengthily from Sevilla’s work, which in turn quoted lengthily from a letter of a witness and related reports.

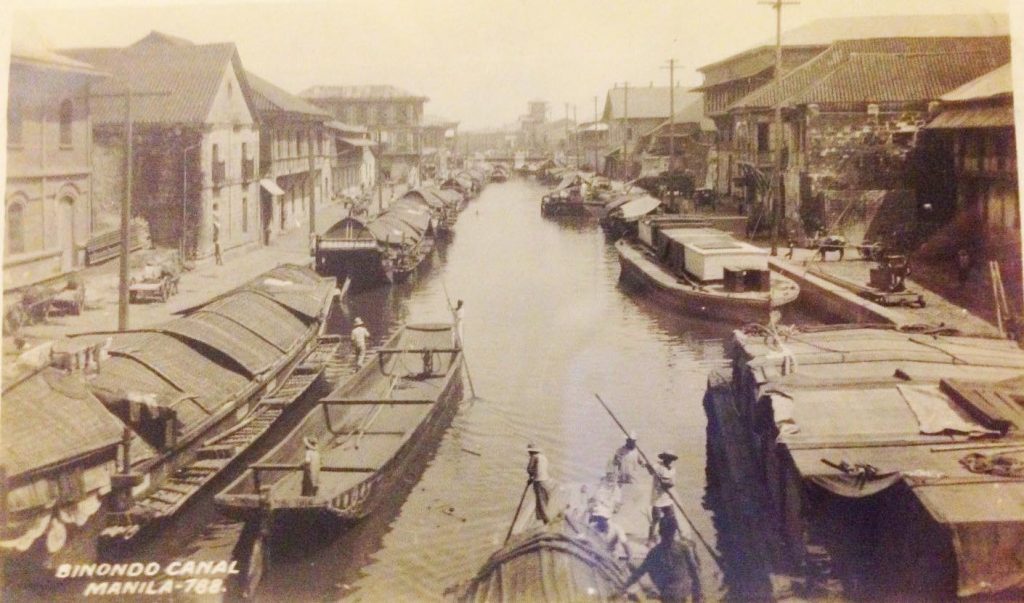

In early October 1820, a severe cholera epidemic ravaged Manila. In a few days after the outbreak, several hundred indios were stricken by the disease and were “dying like flies.” Hardest hit were the indio villages along Pasig River and the people of Tondo town where Balagtas was then residing….

…The highly contagious disease had spread rapidly through the contamination of the water of Pasig River – the city’s main source of potable water.

For most city residents, supply of sweet drinking water came from upstream from an uninhabited lush watershed fringed by thickly wooded river banks toward the town of Pasig, well out of the reach of the saltwater tide from Manila Bay.

From that spot, water was drawn and contained in large earthen jars aboard canoes that regularly hauled and distributed them to private homes and public buildings. In the households of affluent and well-to-do family, drinking water was purified by having it permeate through a filter of a special sandstone rock boulder and collecting the droplets in tall, humid clay kitchen jugs that also cooled the water.

Most poor indio villagers who lived along the river banks used no such filtering device and were accustomed to drinking the water straight from the nearest “clean” source. As a precautionary measure, the corregidor (military governor) of Tondo immediately issued an advisory to all residents to stop using the river water for drinking without first boiling it.

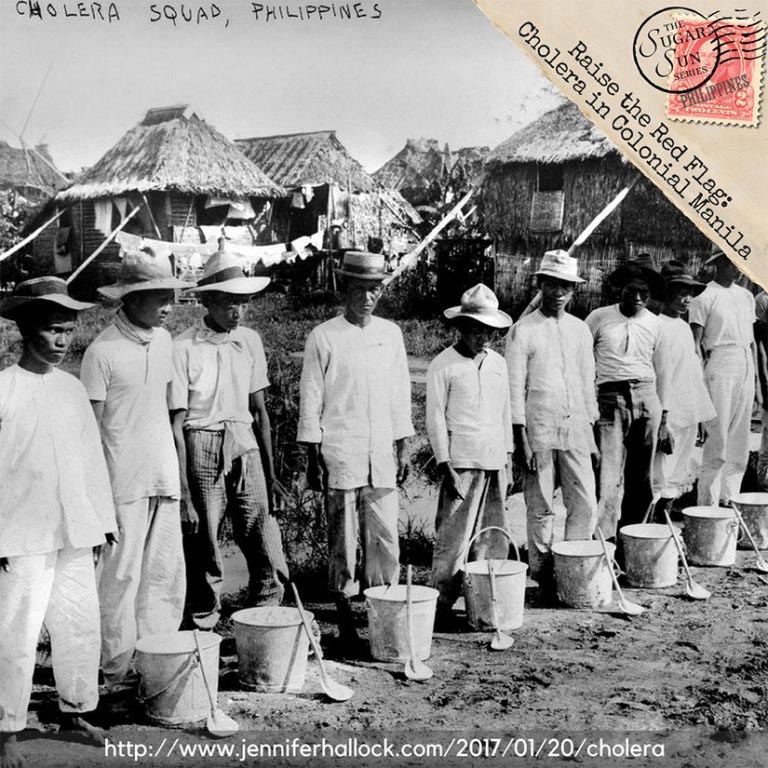

In months to come until the pestilence gradually subsided, thousands of indios, many of them young children, succumbed. To prevent further contamination and spread of the disease, their shrouded corpses were taken daily by pull carts to a secluded cemetery located midway between Arroceros and the town of Paco. They were interred in multitiered rows of pigeon-hole graves built into the cemetery’s two high, circularly laid-out, concentric Intramuros-like stone walls of about a half-kilometer outer circumference – which is now the Paco Park.

But as the stoic indios silently mourned and buried their dead, word soon went around that the epidemic had been caused by the criminal act of poisoning the waters of Pasig River. The nasty report implicated the European expatriates and the other foreigners of Binondo and Santa Cruz, particularly a visiting French naturalist who was undertaking scientific investigation and was collecting and preserving specimens of tropical insects, birds and other animals.

Indio misery and grief turned into instant fury, and true to their Malay character, their instinctive reaction was violent.

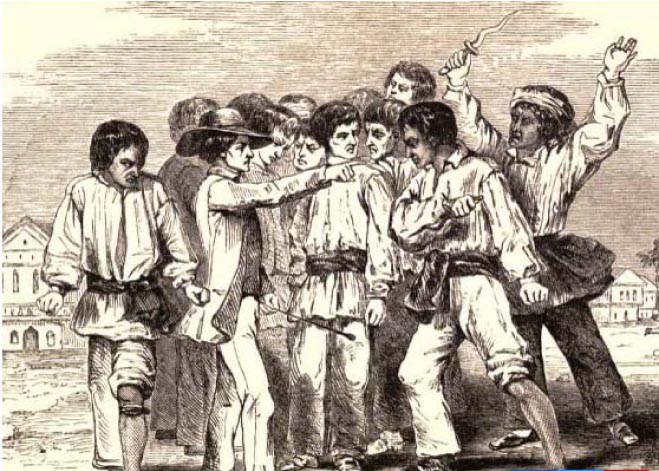

On Oct. 9, between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m., a cold-bloodedly determined mob of male indios, numbering about 3,000 armed with pikes, bolos and clubs, streamed into the town square of Binondo and, in a fit of insane rage, plundered the homes of Europeans and other foreigners in Binondo and Santa Cruz and slew any resident they chanced upon.

And although the then Gov. Gen. Mariano Fernandez de Folgueras (term: 1816-1822) later sent out troops to the scene, the soldiers merely stood by and did nothing to check the rampage which ended at nightfall, leaving a wide swath of destruction and looting and at least 50 Europeans dead. Many others were injured or taken as hostages and brought to Tondo by the indios. Curiously, not a single Spaniard was killed nor any Spanish home plundered.

…The indio rampage resumed the following day and this time they plundered the Chinese sector of Binondo, killing at least 85 Chinese residents. Again, Intramuros troops were called in. But while this time Gov. Gen. Folgueras dispatched a larger force to make arrests, the indio mob quickly dispersed as the troops entered Binondo.

A government committee composed of military and civilian officials was formed to conduct an investigation of the massacres which, shortly after hastily gathering data and coming up with conflicting findings, failed to recommend any definite course of action.

Thereafter, Gov. Gen. Folgueras, who was called upon and somewhat reproachingly pushed by Ayuntamiento (City of Council) of Intramuros to institute proper legal proceedings to bring justice to the victims of the massacre, perfunctorily appointed a commission headed by a ranking member of his staff to conduct a more thorough investigation and submit a formal report on the horrible incident.

Significantly, the two days of dreadful shocking incidents of October 1820 had deep, far-reaching economic and political undercurrents. This was candidly disclosed by American businessman Peter Dobell, then acting as Russian consul in Manila, in an incriminating letter (preserved in the New York City Public Library) written from the city of Macao, South China on Nov. 28, 1820 and addressed to his superiors in London and Moscow.

He had departed from Manila that July and left behind to look after his office in Binondo his 23-year-old nephew who daringly escaped the October massacre.

Dobell, who could have been less lucky had he been in Manila at the time, gave this revealing account:

“I arrived with my wife and daughter at Manila last March and was received with great apparent attention, politeness and hospitality. After living there a couple of months, however, I perceived that there existed a vast deal of jealousy and envy, against all strangers, and particularly those who resided or intended to form establishments in the country.

“Those ignorant people (the Spaniards) could not divest themselves of this feeling, even toward those whose capital, talent and industry were directed to the most laudable pursuits and promised to produce great public as well as private advantages to the colony.

“At this crisis, several French ships were in the port, one or two Americans and an English ship from Bengal. In the French ships had arrived a naturalist sent out by the [French] government to make collections, and some persons who intended to remain in the Philippines to cultivate sugar, cotton and other crops.

“This envious disposition on the part of the Spaniards increased daily against the strangers until an opportunity presented itself of gratifying their malignant hatred in the most cruel and bloody manner and without themselves appearing to have anything to do in the business.

“It is necessary first to tell you, that the new Constitution [the Cadiz Constitution of 1812 repromulgated by Spanish King Ferdinand VII] had been received during the prevalence of this feeling, giving extensive privileges and liberal encouragement to foreigners who think it proper to settle in the Philippines and rendering the natives as free and equal, in rights, as their former masters.

“These certainly made them [indios] a little unruly, but if not secretly instigated, it would never have induced them to commit a crime that makes humanity shudder.

“The ship from Bengal was the Merope Captain Nichols and it was supposed she had brought into the colony the epidemic that had ravaged all India this year under the name of the Cholera morbus. It made its appearance in the beginning of October last, carrying off great numbers of the indios every day.

“The humane French and other strangers who beheld these miserable wretches dying around them without any medical aid, freely administered what medicine they had, and were actively and daily employed in endeavoring to alleviate the distress and cure the complaints of all those who lived within the sphere of their exertions.

“This also became a cause of jealousy and hatred and the villains began immediately to exasperate the indios by saying: this poisonous disease was introduced by the French and the other strangers, they have poisoned even the waters and they administer poison to the sick, purposely to exterminate the whole race of Tagalians.

“The ferocious indios wanted nothing further to excite them to deeds of blood and plunder. On the 9th of October, about 10 a.m. and 11 a.m., they collected to the number of about 3,000 men armed with pikes, knives and bludgeons and proceeded coolly and deliberately to plunder and massacre all the strangers on whom they could lay their hands!

“I have no time to give you the details of this shocking business, but you will certainly read them in the gazettes as I have sent both to England and Russia very full accounts for publication.

“Suffice it now to say that the governor general and the authorities were vainly implored for assistance. They came, it is true, with the troops, but it was only to behold with sangfroid the horrid spectacle.

“Not a musket was fired to save the lives of those unfortunate and defenseless strangers, who, to the number of 39 were plundered and cruelly massacred; some of them were so cut up and mangled, it was impossible to recognize them.

“As most of them were not Roman Catholics, they were all collected and thrown into a hole together without the shadow of a ceremony or a stone to mark their graves! What is worse, the last accounts from there, down to the 9th of November, mentioned that not a Spanish life was lost, nor has a single native as yet suffered punishment for this most atrocious and horrible deed.

“My house was attacked and pillaged, my nephew and Mr. Prince of Boston, who live with him, made prisoners, and after being near two days in the hands of the indios, suffering the most abominable treatments, they luckily escaped death.

“Eighty-five Chinese and 11 English seamen were also plundered and assassinated. …But what will give the death blow to the prosperity of the Philippines is the late horrible massacre. All those French and other foreigners, who were anxious to have established themselves in commerce or on estates in the country, are now frightened off and certainly, no one will find himself confident enough to trust a government, which could permit such a massacre to take place, immediately under its eyes, when it had 5,000 men in arms, ready at a minute’s notice to disperse the mob.”

On Oct. 20, 1820, Gov. Gen. Folgueras issued a decree that harshly castigated “the indios of the Philippine Islands and especially those of the district of Tondo” who, “led astray and infuriated by certain malicious persons” gave vent to “general frenzy to commit grave acts that violated the laws of civilized nations.”

The decree ridiculed as foolish and absurd the indio notion that the foreigners of Manila poisoned the waters of Pasig River which, it said, “even the mountain Negritos, or the Moros of Jolo and Mindanao would be ashamed to entertain.”

Patronizingly, it reminded the indios that the people they had plundered and killed were not only friends and brothers but were the very persons on whose enterprise the prosperity of the colony depended because they provided the market for the products of the country.

Gov. Gen. Folgueras made public the report of the commission he appointed on Oct. 13, which concentrated its investigation on determining the culpability of the foreigners accused of poisoning the water of Pasig River.

The report concluded that the above-mentioned specimens could “serve no other object than to enrich the cabinets of natural history,” and that all the other items presented as evidence could not in any conceivable way be used to harm human beings.

In closing, the report lamented the fact that the ridiculous indio notion – that the cholera epidemic was caused by the poisoning of the waters of the Pasig River by the Europeans of Binondo – was accepted by so many people who knew better than to believe such a bizarre tale.

But it is certain that they did, and, among them, many of the clergy; and with this the delusion attained such power that it has caused the very scandalous deeds which all good persons lament; for it is certain that there is no better way of propagating an error than for persons of authority to adopt it.

There is no doubt, it appears, that this foolish idea of poisoning had its origin in the ignorance of the indios; but there is as little doubt that malicious persons, imposing upon this folly and lack of knowledge in the indios, incited them to perpetrate the assassinations and robberies of the disastrous days, Oct. 9 and 10.

The report made no mention, as it disapproved the accusation against the foreigners of Binondo of poisoning the river, that it was apparently one of the ships from Bengal docked at Pasig River that brought the plague that had ravaged India early that year.

Gov. Gen. Folgueras, in his decree, exhorted the indios: to repent for the murderous acts they committed, to denounce to the authorities the instigators of the massacres, to surrender the perpetrators of the killings and plunder and to restore to the aggrieved foreigners their stolen properties.

His call was especially addressed to those indios of Tondo who had taken part in the massacre, as he described Binondo as “the theater of the most horrible tragedy and has covered itself with blood and ignominy.”

But after issuing the decree and making public expressions of righteous indignation, Gov. Gen. Folgueras took no further action and, from all indications, had considered the matter closed. Thus, Peter Dobell, writing more than a month after the incident, disgustedly reported:

“I must close my letter by informing you that the captain general has refused all the applications for indemnification for those who have been plundered; so that as yet, neither the punishment due to the assassins has been inflicted nor redress made to the unfortunate people who were robbed.”

The case of the horrible massacres of Oct. 9 and 10, 1820 was swept under the rug and soon conveniently forgotten by the Spanish colonial authorities.

Who provoked the massacres? The instigators could be identified by the motive and methods used. Who among the feuding sectors of the multiracial society could benefit from instigating such a murderous act?

To the innocent victims of the massacres and to the poor indios who had been misled and manipulated, the whole scenario became self-evident after the incident and after the fact-finding team of Gov. Gen. Folgueras presented a “whitewashed” and deflected report.

The motive was clearly to strike a fatal blow on the flourishing European expatriates and the Chinese merchants of Binondo who, particularly in the last two decades, had competitively dislodged the Spanish merchants in the overall control of the economic life of the colony.

The preponderance of circumstantial data incriminatingly point to a direct involvement of the ruling peninsular elite of Intramuros in spreading the nasty rumor that incited the indios and in tolerating and doing nothing to stop the two-day rampage – even as Gov. Gen. Folgueras and his fact-finding team performed a good job in “whitewashing” and deflecting the issues from themselves.

The Binondo and Santa Cruz merchants, who had acquired enormous wealth and dominated both the external and domestic trade of the country because of their business acumen and resourcefulness, had become the object of envy and hatred of the Spanish ruling peninsulars.

The Spaniards felt that they were being deprived of what was their rightful privilege as proprietary beneficiaries of the trade and industry of the islands: the foreign merchants had gone too far in beating them in their own turf to the point of seriously threatening their personal fortunes.

From the above account, we see how the envy, distrust, and hatred of the Spaniards against their competitors who threatened their personal fortunes – foreigners, including the Chinese – had led to this most unfortunate incident. In times of economic crisis, we still see people who become convenient scapegoats for the failures of administrators. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 29, no. 9 (October 4-17, 2016): 9.