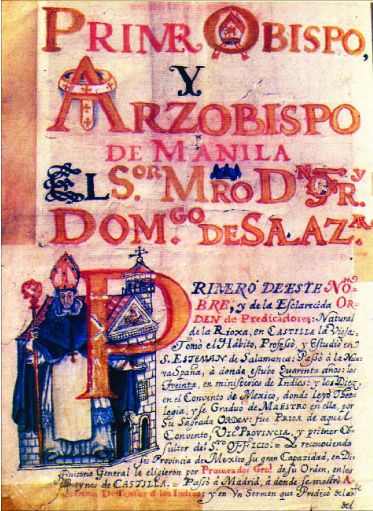

The book, Domingo De Salazar, O.P. First Bishop of the Philippines (1512-1594): A Study of His Life and Works, by Lucio Gutierrez, O.P., reveals the early years, milieu, student and missionary life of Domingo de Salazar, the Philippines’ first bishop and one of the key figures of the Church. It also gives valuable insights into his relationship with Chinese in the Philippines.

Domingo de Salazar was born in 1512 (historians have no exact birthdate) in Labastida, a small town of the Rioja Alvesa in north-central Spain. His parents, Diego Lopez de Salazar and Ana de Cariga, sent him to the University of Salamanca, where he enrolled in the Faculty of Canon Law and later in the Faculty of Civil Law from 1526 to 1539.

One who greatly influenced the young Salazar was Bartolome de las Casas, the protector of the natives of America and ‘Father’ of the New World.

Salazar was later called “the las Casas of the Philippines” due to his fighting spirit and defense of the Filipino natives against the abuses and injustice of the royal Spanish officials and Filipino datus.

Salazar joined the Dominican Order in 1545. He was sent to Mexico, where he devoted himself to the conversion of the natives of the province of Guajaca. He was then sent to Florida, where he spend many years in toil and privation. He was later recalled to Mexico to be prior in his convent.

In his 40 years of missionary life, Salazar made political enemies who attempted to thwart his work and succeeded in throwing him into prison when he sought an audience with the king.

It was then that he got the attention of the king, who proposed to the pope that Salazar be made bishop of the Philippines.

On Feb. 6, 1569, King Philip II appointed him as the Philippines’ first bishop. His initial reluctance was set aside as his missionary zeal to convert China spurred him.

Salazar found the Chinese a highly intellectual people, although there were only a few Christians among them. And because the Philippines is very near China, he thought that it would be strategic to convert the Chinese in the Philippines and prepare them as well for his mission.

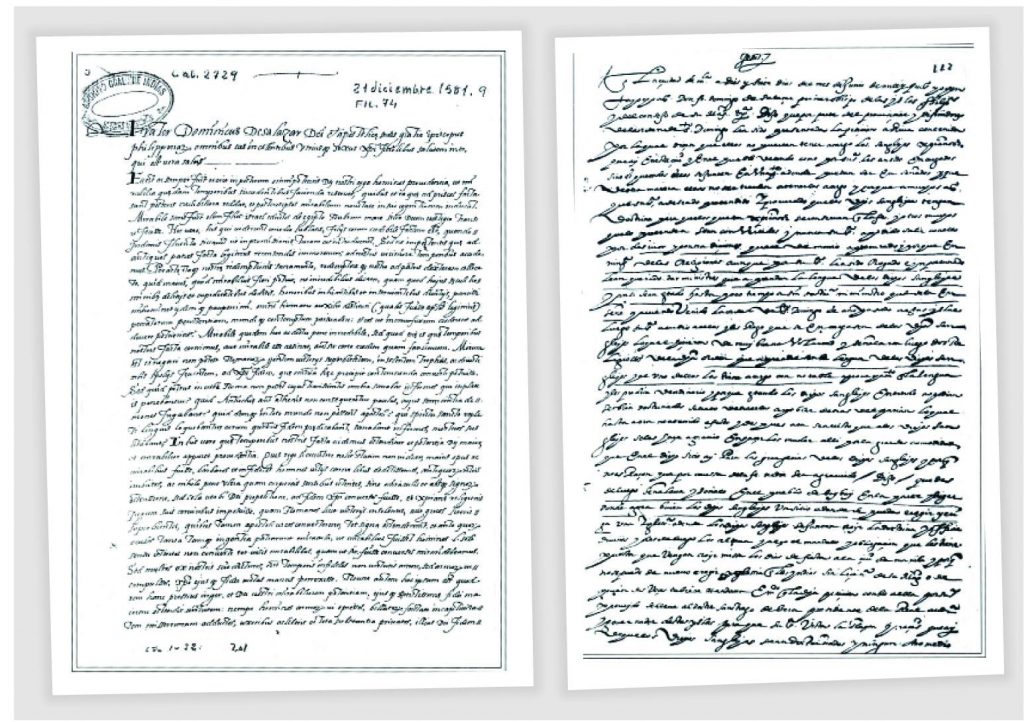

In one of his letters to King Philip II dated June 24, 1590, he said: “I have long wanted to attempt the conversion of China. I came to these islands for that reason, knowing that they were near China and that many Chinese lived here.”

Together with one surviving Dominican, Fray Cristobal de Salvatierra who became his trusted secretary, and a Jesuit Father Alonso Sanchez, Salazar set foot on Philippine soil in March 1581.

The Manila Synod

The zealous Salazar immediately noticed what was wrong in the Philippines: it was a flock without a shepherd.

He espoused the cause of the Filipino with a fearlessness that he was called the “intrepid Salazar.”

He felt the need for reforms, especially with the way the Spanish colonizers treated the Filipinos, and the way the religious members conducted their affairs.

He convened a council, called the Manila Synod of 1582, composed of his fellow missionaries and some laymen to decide on matters concerning how they should conduct themselves, what their roles should be, as well as how to correct the mistakes committed by the Spaniards.

The Synod took into consideration some observations about the Filipinos: “The Indians had very good governance in some things. They had some good things and those should not be changed.”

The Chinese-Filipino Apostolate

As more and more Chinese traders (Sangleys) came to the Philippines and an increasing number migrated and settled here, the missionaries carried on the task of evangelizing them.

The early missionaries, Augustinians and Franciscans, taught Christianity in the Filipinos’ native language.

Salazar, however, thought that it would be more effective to use the Chinese language with the Chinese in the Philippines. Even before he came to the Philippines, Salazar believed that the mainland Chinese were an intellectually superior race.

He thought that it would be strategic to begin with the Chinese in the Philippines by evangelizing and baptizing them. Thus, he and the Dominicans initiated a separate apostolic project that would undertake not only the Chinese conversion but also learn and utilize the Chinese language.

With more Dominicans coming in 1587, the teaching of Christianity to the Chinese gained momentum.

In 1594, Luis Perez Dasmariñas purchased the district of Binondo and later donated it to the Chinese to carry out missionary activities. The acquisition proved to be helpful, especially in the recognition of the Chinese language in its role in evangelization.

Holy Rosary Church and hospital

The Dominicans, continuing the efforts and initiatives of Salazar, put up the Holy Rosary Church in Binondo in 1596, known today as Our Lady of the Most Holy Rosary.

The Binondo Chinese Parish was dedicated to evangelizing the Chinese, conducting baptisms and other sacraments.

The Dominicans also built the Hospital de San Gabriel for the Chinese, relying on donations from charities. Some contributions came from the Chinese themselves. News of this concern of the Dominicans reached China, which acknowledged such kindness toward their countrymen in the Philippines.

Cutting-off pigtails

Salazar asked the Chinese converts to cut off their pigtails if they were to embrace Christianity. He reasoned that the absence of pigtails would distinguish the converts from the non-converts, and especially from the Chinese in the mainland as there were Chinese Filipinos who went to China.

This met resistance, so much so that most Chinese chose not to be converted. In mainland China, only the much-despised bandits and criminals had their pigtails cut off.

Gov. Santiago Vera also opposed it, saying that the pigtail is a matter of custom and not a ceremony. King Philip II also signified his displeasure with Salazar’s decision.

The Parian

Salazar had generally good impressions of the Chinese. In 1590, he reported to King Philip II about the Parian: This Parian has so adorned the city that I do not hesitate to affirm to Your Majesty that no other known city in España or in these regions possesses anything so well worth seeing as this; for in it can be found the whole trade of China with all kinds of goods and curious things which come from that country. These articles have already begun to be manufactured here, as quickly and with better finish than in China. In this Parian are to be found workmen of all trades and handicrafts of a nation, and many of them in each occupation. They make much prettier articles than are made in España, and sometimes so cheap that I am ashamed to mention it.

The governor general, however, who might have been intimidated by the growing number of Chinese and their influence, held an opposite view from Salazar’s and regarded the Chinese as mean, vicious, deceitful and a threat to the Spaniards.

Such impressions and animosity might have triggered unfavorable reactions from the Chinese. The Spanish report of a revolt in 1603 states that Chinese mandarins initiated it to retaliate against abuses.

Meanwhile, Chinese records reveal that the 1603 “revolt” was a revenge-massacre of the Chinese by Gov. Gen. Luis Perez Dasmariñas, whose father, Gomez Perez Dasmariñas, was killed in the 1593 mutiny led by Pan Ho Wu.

Salazar’s conflicts

Salazar’s reign was not a smooth one. His friction with the governor general, his disagreements with the other religious orders, and at times the disapproval of the King Philip II definitely gave him headaches.

He also lamented the lack of qualified missionaries in the country to help support his efforts. His single-minded pursuit of clean governance met a lot of resistance from Spanish authorities.

He also had conflicts with the Holy Office of Inquisition in Mexico that later charged him of illegally usurping their powers, which he questioned, considering that they had no jurisdiction over him.

Salazar was hot-tempered yet he was hardworking and sincere in his efforts about his mission and concern for the Filipinos, including Chinese in the Philippines.

In his letters, he reported to the King of Spain the abuses and the conditions that he saw. In one of his letters, he expressed his disappointment over the malicious description Portuguese made of the Chinese. Salazar found the Chinese grateful for teaching and guiding them.

Return to Spain

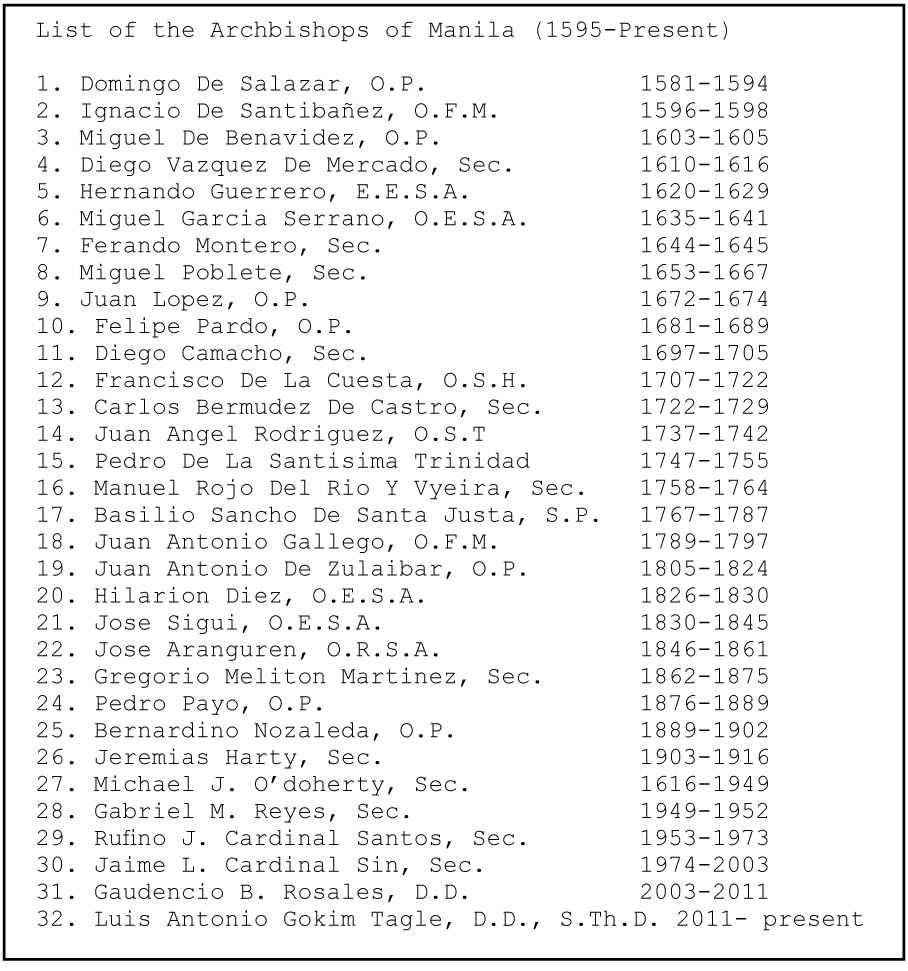

Within the span of time Salazar stayed in the Philippines as bishop (1579-1594), he accomplished a lot. He held a synod of the clergy, erected a cathedral, regulated the internal affairs of the diocese, opened a college and established a hospital.

Salazar was almost 80 when he returned to Spain in 1591 to plead in person the cause of the natives with the king.

He reported to King Philip II not only about the reforms he initiated and his accomplishments but also about the sad conditions of the Filipinos, including the abuses against them.

With his success, Manila was elevated to a metropolitan see with Salazar as its first archbishop. But before he could receive the papal bull of appointment as archbishop of Manila, Salazar got sick.

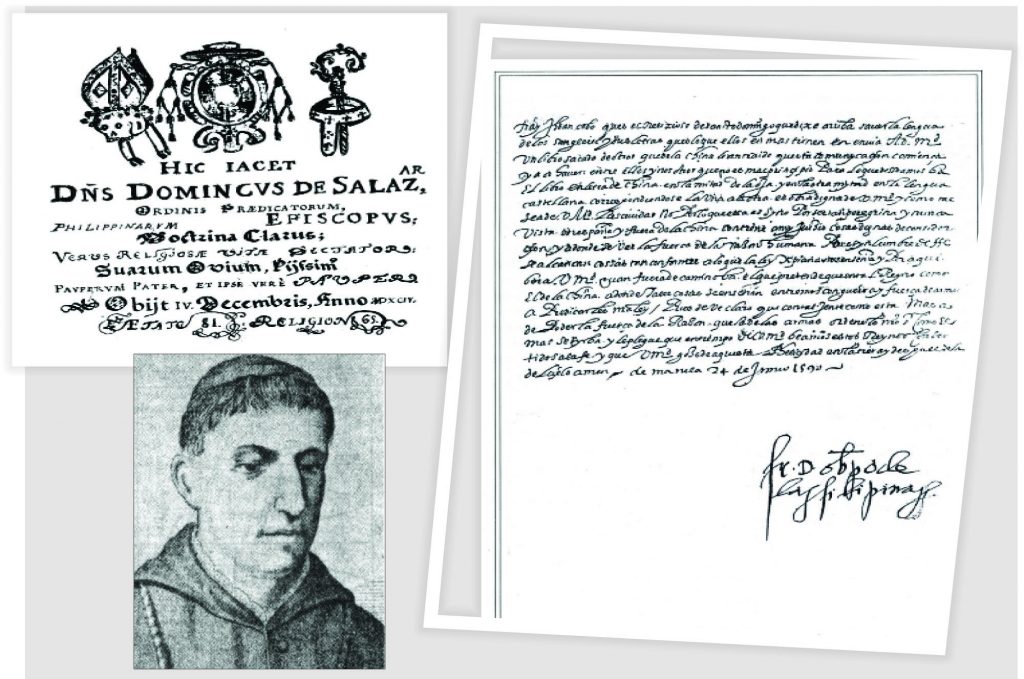

He begged Fr. Andres de San Millan, a Dominican from San Esteban of Salamanca, who attended to him in his sickness, not to bury him as bishop, but as a simple friar, dressed in the habit of his order, but with the miter and the staff.

Salazar died in extreme poverty and was buried in the chapter room of the convent of Santo Tomas in Madrid.

On his epitaph was written: “Here lies Don. Fr. Domingo de Salazar of the Order of Preachers, bishop of the Philippines, of sound doctrine, a true follower of the religious life, most pious shepherd of his flock, father of the poor and in himself truly poor. He died 4th December of the year 1594.” — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 29, no. 5 (August 9-22, 2016): 8-10.