Situated at the instep of the Italian boot, Matera lies on one side of a valley’s slope, descending to a deep rocky river ravine known locally as La Gravina.

This southern Italian city was founded by the Romans in the third century B.C., and its prehistoric cave dwellings are believed to be one of the first human settlements in Italy.

We arrived at Matera after sundown. Our first sight of the city was a surreal experience: an old church and pale landscape of dimly lit stone houses, haunting yet fascinating. It seemed time stood still, and I imagined I time-traveled back to ancient Jerusalem during the time of Jesus Christ.

It is easy to understand why Mel Gibson chose this site as the location for his film “The Passion of the Christ,” as other films like “The Young Messiah” and “The Gospel According to St. Matthew” were likewise filmed here.

After walking through alleys and stone stairways, we found our hotel, Hotel Caveoso.

Everything in Matera is about caves. The reception, our hotel rooms and bathrooms are all inside caves. No two rooms are alike – eerie but interesting, ancient yet equipped with Wi-fi, cable television and heater.

Until now, I can’t get over the idea that I slept in a room that could have been inhabited some 9,000 years ago.

The next day started with a morning walk along a maze of winding alleys, each so similar to the other one can easily get lost. I soon realized that abandoned stone buildings surrounded our hotel, some with overgrown vines. I ended the walk abruptly as the 2°C wind was biting into my double-layered clothing.

After breakfast in the cave-cafe section of the hotel, we headed off to meet our guide, Antonio Manicone, a professional guide born in Matera who gives tours not only in Matera but in the Basilicata region.

He started the tour by bringing us to a higher area in Matera’s modern town, the only place from where you can see the ancient Sassi. The quiet, ancient town is known for its Sassi di Matera (stones of Matera), according to Manicone. Dug into a stone cliff and carved out of volcanic tufa rocks, the houses are built one on top of the other, with some rooftops serving as narrow alleys and stairway streets.

Passing through these alleys, we noticed many unoccupied houses. Manicone pointed out that these ancient cave-dwellings were shared by humans and their cows, sheep and pigs – all together in one chamber.

The traditional house is a cavern, with a kitchen situated immediately beside the entrance. This way, the chimney does not protrude through the middle of the alley above. The middle section is the living quarters, while an ante-chamber at the back is for the livestock.

These houses are perfect examples of negative architecture where materials are carved away to create space, in contrast to positive architecture where materials like hollow blocks, steel, cement are added to build a house.

Once dubbed as the “Shame of Italy,” hundreds of families, roughly 16,000 people, mostly peasants and farmers, crowded in these cave-dwellings without electricity or running water.

With no proper sanitation, living conditions were at its worst. The impoverished residents were plagued with malaria, cholera and other epidemics.

Matera at that time was synonymous to poverty. Most of the population worked as slaves in exchange for land and daily food rations but did not have the ability to save. The deplorable state was considered a national scandal.

In the 1950s, the Italian government passed a law to relocate the residents from the Sassi to the modern town of Matera, constructed on the plateau above the slope. But without much savings, the residents had difficulty moving out. Those who did had a hard time adjusting to the new houses designed by avant-garde architects. The new residents were in a dismal state.

In the next few years, the remaining residents were forced out, leaving Sassi an empty shell. Buildings were erected in the modern town to wall up the ancient town, as if erasing such memories.

Deeply ashamed of their past, many old people from Matera to this date refuse to talk about it, let alone revisit the place. It was not until the 1980s when the ancient town was reopened for development that some former residents started to move back.

In 1993, UNESCO made Matera a World Heritage Site and people started to take interest again in this ghost town. It was cited for being “the most outstanding, intact example of a troglodyte settlement in Mediterranean region, perfectly adapted to its terrain and ecosystem.”

To prepare Matera for welcoming back inhabitants and curious tourists, electricity, plumbing, ventilation and heating systems were installed under the alleys and these were restored back to its original look. The old cave-houses were converted and renovated to comfortable dwellings, while abandoned ones were transformed into hotels, B&Bs, restaurants, cafés and galleries.

The Sassi of Matera is now divided into Sasso Calveoso – where our hotel is located – and Sasso Barisano.

Water harvesting

Because of Matera’s terrain, getting water was a challenge. The ancient residents collected rainwater that ran through seepage for filtering before flowing into bell-shaped cisterns (palombaro).

Since houses were on top of each other, three or four families would share a cistern located at the lowest house level.

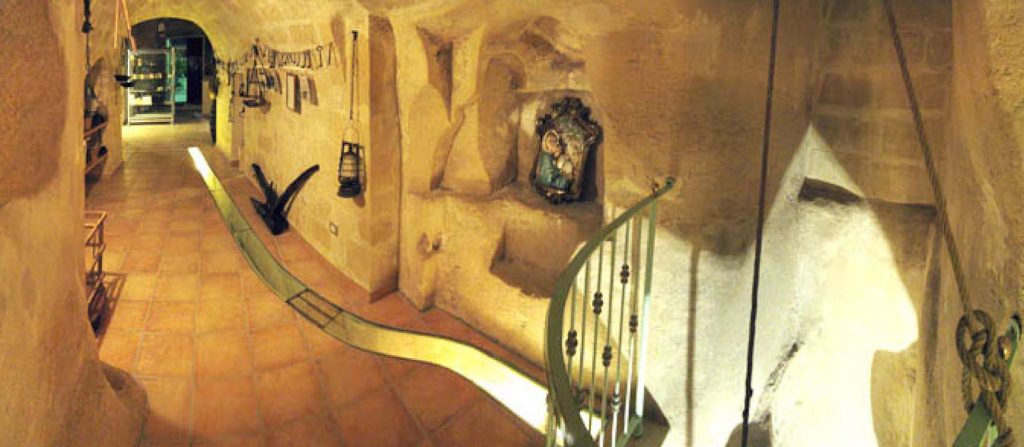

To have a better idea of how this works, Manicone brought us to La Raccolta delle Acque, the water harvesting museum.

Here, we got to see a typical house, domestic and communal cisterns, and canals around the houses that led rainwater to other parts of town to avoid flooding in case of overflowing rainwater.

Aside from domestic cisterns, there were bigger palombari for the community’s use. The pillars of these palombari were carved from rocks with a vault height of more than 15 meters. It looked like an underground cathedral and is navigable by boat. Eels are put into these palombari to prevent water from stagnating.

The largest cistern, Palombaro Lungo, is found under Piazza Vittorio Veneto, but unfortunately it was not along our tour path.

These cisterns were eventually turned into houses, while domestic cisterns with its cold interior were used to store food, especially during winter time. Quite an ingenious technology during those times.

Cemetery and churches

The next important stop was on a cliff top overlooking the Gravina. This plateau is right above the former monastic complex and served as the local cemetery known as Cimitero Barbarico.

“This is the place where the dead are on top of the living,” Manicone joked.

The tombs, carved out of rocks, seem too small for normal humans. The tombs have small notches on the top edge to fit tombstones, although the tombstones are no longer around.

Manicone shared that his grandmother, together with other town ladies, strung up clothesline here to dry clothes faster.

There are about 155 churches around Matera, with others inside caves across the ravine. In the olden times, when shepherds got stranded by nightfall on the other side of the cliff, these cave-churches offered a place to sleep to survive the night.

Bigger cave-churches referred to by locals as Chiese Rupestri (Rupestrian Churches) were mostly excavated by the Basilian monks fleeing persecution during the Byzantine Empire, the eastern half of the Roman Empire.

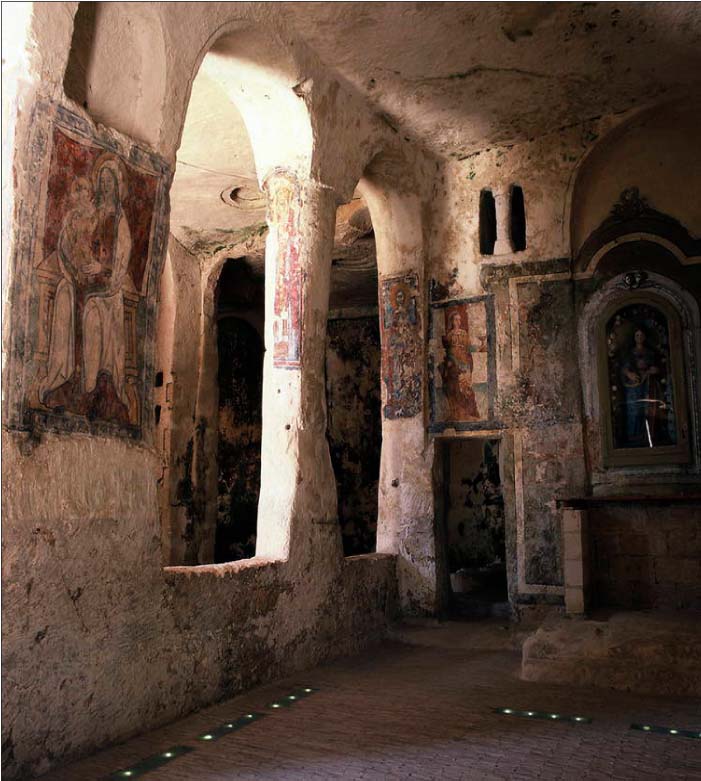

We visited the Santa Lucia Alle Malve, the first female monastic settlement of the Benedictine order. Originally dedicated to Sant’Agata (Saint Agatha) between 1217 and 1267, then to Santa Lucia and Sant’Agata, the convent finally became known simply as Santa Lucia.

The church has a nave and two aisles, with an apse separated by pillars. The left-hand aisle and nave were part of the original church, while the right-hand aisle was incorporated with the church in 1310.

Fragments of a fresco can still be seen on the wall, “depicting a holy monk, a probable Santa Lucia in 1537, the right side of the head of Sant’Agata and a left arm in Gothic style.”

On the first pillar on the left was a painting of Madonna and Child. The church was later converted into a residence. This is evident by the kitchen on the left side of the entrance door.

Back to Caveoso

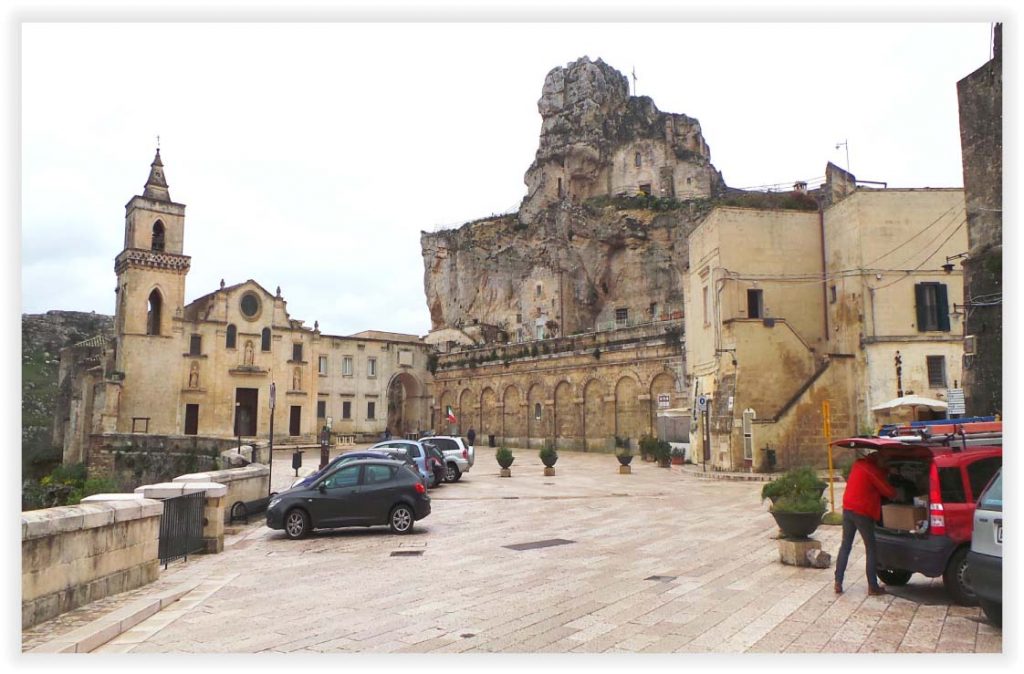

The two-hour walk brought us back to Sasso Caveoso where the San Pietro Caveoso church built in 1218 stands grandly. This was the church I saw the night we arrived and is within walking distance from our hotel.

Manicone ended his tour with showbiz gossip: the movie “Ben-Hur “was filmed last year in Matera, and the previous day he bumped into the film crew of the new “Wonder Woman.”

Matera was an unexpected, rare find on this trip. Isolated and long forgotten, people are now rediscovering this interesting, picturesque little town. Visitors are still lean compared to the other well-known Italian cities, but great things are in store for Matera.

No longer the disgrace of Italy, Matera on Oct. 17, 2014 was declared the Italian host of the European Capital Culture for 2019, together with Bulgaria’s Plovdiv.

Tourism has changed the fate of Matera, a place where once no one wanted to return. Although the modern town of Matera has high-end shops and upscale cafés, it is this timelessness and mystery that became the highlight of our trip. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 29, no. 4 (July 19-August 8, 2016): 14-16.