Imagine, even during the time of Dr. Jose Rizal, Chinatown in Binondo had been the underground base of Filipino revolutionaries.

This and other fascinating stories about the Philippine Revolution and the Filipino-American War are compiled in The I-Stories: The Philippine Revolution and the Filipino-American War as told by Its Eyewitnesses and Participants by Augusto V. De Viana (UST Publishing House, 2006).

De Viana found this interesting vignette published in periodicals such as the Philippines Free Press and the Manila Times between the 1920s and 1950s while doing his master’s thesis.

In particular, the Philippines Free Press (Dec. 26, 1953) wrote about the house of Dr. Jose R. Francisco in Binondo that was part of what we may call “Manila’s underground” during the late Spanish period.

Francisco was among the few people living in the 1950s who actually saw Rizal. His father was Binondo textile trader Don Higino Francisco.

The Franciscos were related to the Mercados of Biñan, who included Rizal’s father, Francisco Mercado.

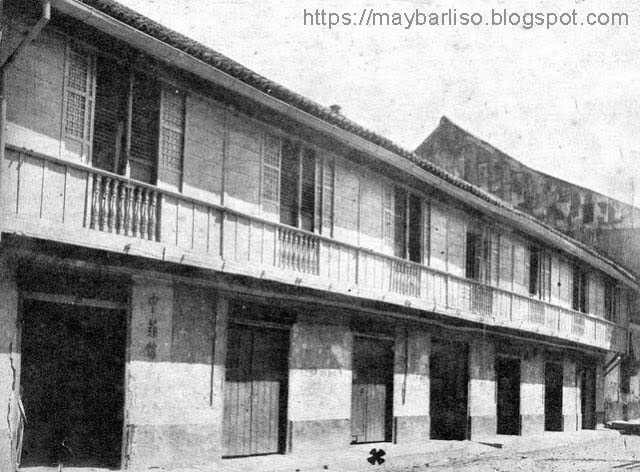

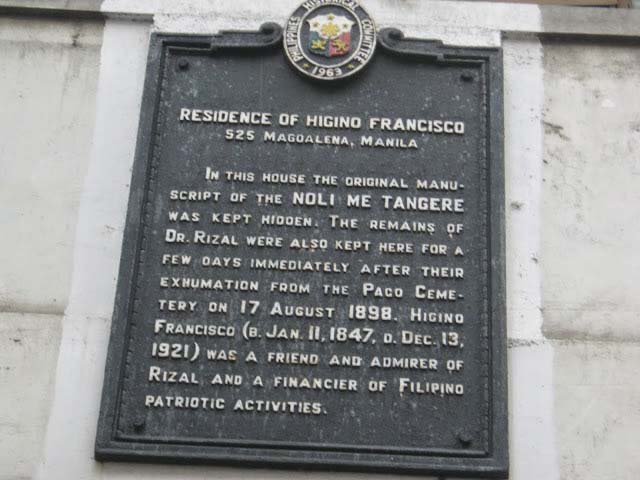

Don Higino’s home was a large house on San Jose Street, later renamed as Magdalena St. (now Guillermo Masangkay St.) in Binondo. Behind the house was Estero de Tetuan, the navigable waterway used to transport goods in Binondo.

Don Higino’s house served as a convenient rendezvous for people wanted by the Spanish authorities because of their filibustering activities and as a drop-off and pick-up point of political propaganda materials.

One day in 1892, in the old house in Binondo, Don Higino called Dr. Jose, his brothers and sisters to go downstairs. He told them that the famous Dr. Jose Rizal had arrived and expressed a desire to meet his young relatives.

The children went downstairs and lined up in a row in the sala. They obediently waited for their father to appear from the door leading to the street.

Following Don Higino was a young man, dressed in black. Dr. Francisco, who was about eight years old at that time, described the stranger as “handsome but rather short.”

“This,” said Don Higino, referring to the man, “is your Tio Jose.”

Jose Rizal walked down the row of children who numbered eight in all. He carefully looked at each of their faces.

“I think,” said Dr. Francisco, “that he was searching for the family resemblance.”

Before his arrest and deportation to Dapitan by the Spanish authorities, Rizal entrusted the original manuscript of the Noli Me Tangere to Don Higino who kept it in his textile store on Calle San Fernando at the foot of Binondo bridge. Fearing that the Spanish authorities might search the store, Don Higino hid the manuscript under the bridge itself.

Don Higino’s children felt that the house was becoming full of strange secrets. From time to time, a bundle of newspapers would arrive from nowhere. People would casually drop by and leave with a copy of one of the newspapers hidden in their clothes. The newspapers had different names and one of them was La Solidaridad.

Like the mysterious papers were the visitors who kept popping out from nowhere. Very often at night, a banca loaded with zacate or horse folder was paddled up to the kitchen steps at the back of the house. From under the zacate, a human figure would rise and move into the embarcadero and run into the house.

The next day, Dr. Francisco and his brothers and sisters would find new faces at the breakfast table.

“This is your Lolo Francisco Mercado,” Don Higino would say, or it might be Lola Teodora Alonzo, or Tio Paciano or Tia Sisang.

The Rizal family was being sought by the Spanish authorities. Its members had scattered and gone into hiding. The Francisco house became what many would call a pre-revolution “underground.”

Dr. Francisco and the other children never knew the identities of most of their mysterious guests.

There was a large room in the house which was always locked and only Don Higino could enter it. Whenever he went in to that room, Don Higino always carried with him food or water.

At one time, Dr. Francisco was given an opportunity to enter the room when he was asked by his father to bring a chamber pot “to Don Felipe Agoncillo.”

When Rizal was executed at Bagumbayan, several members of the family gathered at the Francisco house.

From the behavior of the elders, the children knew that something terrible had happened. Christmas had just passed and it was very close to New Year’s eve.

Despite the festive atmosphere at that time, an eerie atmosphere reigned in the house. Dr. Francisco remembered that he and the other children felt “as if the sun had set.”

There were rumors that Don Higino was planning to snatch Rizal from his prison cell at Fort Santiago.

Later, the Francisco house was raided by the authorities and a small cache of arms was discovered. They arrested Don Higino and detained him at the Bilibid prison.

He was released about a year later when Governor General Primo de Rivera proclaimed an amnesty as one of the conditions of the Pact of Biac na Bato which concluded in December 1897.

To complete the role of the Francisco house in relation to Rizal, the author further wrote:

In August 1898, the Americans took control of Manila. The Rizal family requested the American authority to allow them to exhume Rizal’s remains at the Paco Cemetery.

Don Higino was with Rizal’s family when the hero’s grace was dug up. He took the remains to his house and Dr. Francisco, who was 13 years old at that time, helped his father clean and wash Rizal’s bones at the kitchen steps along the Estero de Tetuan.

Dr. Francisco observed that Rizal’s bones were fine and small. One of his ribs was broken and his brains were still liquid inside the skull.

The hero’s chistera or bowler’s hat, silk handkerchief and black shoes were still quite intact. The rope that bound him had decayed in some sections.

Don Higino gave the bones to Rizal’s mother. He also returned to her the original manuscript of Noli.

Thus, even during the Spanish time, Binondo was not only a business center in Manila but also a hotbed of revolutionary activities. That is the Binondo that must be etched in our memories! — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 29, no. 5 (August 9-22, 2016): 5.