Ed’s note: Condensed and revised from the original paper presented at the 2015 Regional Conference organized by International Society for the Study of Chinese Overseas, with the theme “East Asia and the Chinese Overseas.” The full academic paper will appear in the upcoming issue of TCEA Journal.

Like the Chinese in the Philippines, the Chinese in Korea experienced periods of social, political and economic discrimination. Yet, the Chinese-Filipino community achieved greater economic successes than did Chinese Koreans.

The parallels in their historical narratives had disparate impact: the Chinese in Korea were isolated from the mainstream society while those in the Philippines became well integrated into its host community.

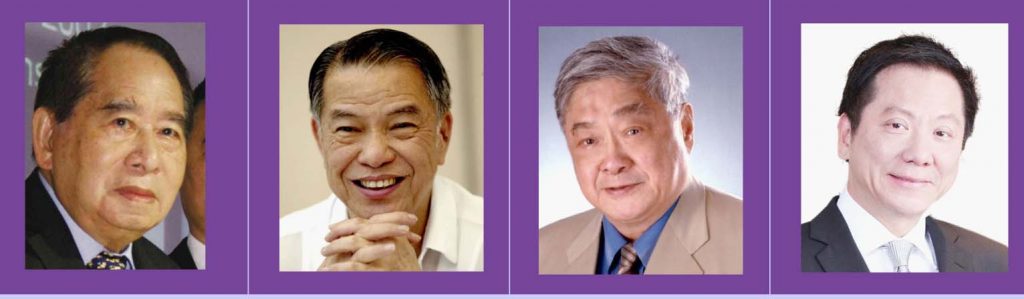

Taipans and Chaebols

The economic success of ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia in business and industry was not replicated in Japan and Korea. In the “Forbes list of South East Asian people by net worth,” many Chinese Southeast Asian tycoons are listed among the “world’s billionaires,” but not those in Korea and Japan. Famous Chinese Koreans are mostly artists, entertainers and athletes.

In Korea, there are no Chinese-owned rich conglomerates like the Chaebols, such as Hyundai, Samsung, Lotte, LG and Daewoo. There is no simple explanation.

Historical, political and socio-cultural experiences of the ethnic Chinese in the two regions conspired against economic success in Northeast Asia but spurred the spectacular successes of the Chinese Southeast Asians. Perhaps, the most important factor that explains this economic disparity lies in the successful integration and assimilation of the Chinese in Southeast Asia versus isolation and lack of integration in Northeast Asia.

Numbers, origins

In the Philippines, some 90 percent of the Chinese are from Fujian and only 10 percent from Guangdong. This makes them a more homogenous group and helps strengthen communal identity. It also makes the Philippine Chinese community – predominantly merchant or business-based – unique in Southeast Asia.

In 2000, Korea had 53,963 Chinese, 90 percent of whom are from Shandong province. In addition, there are some 400,000 new immigrants from China. They are the biggest minority community in Korea, making up 36.5 percent of all foreign residents, according to the Annual Embarkation Statistics published by Korea’s Ministry of Justice.

Most of the huaqiao in Korea are in the service sectors: food and restaurants, Chinese medicine, retailers and specialty shops, tourism and entertainment.

Origins, political orientation

Local-born ethnic Chinese with Southeast Asian identities count several generations, beyond 20 generations for Indonesia and Thailand.

Filipinos of Chinese ancestry can count beyond 10 generations and most ethnic Chinese Filipinos belong to at least third and fourth generations. Chinese Filipinos number 1.2 million people, forming 1.2 percent of total Philippine population. Before the war, as with Korea, most Chinese organizations have the words lu fei (旅菲 sojourning in the Philippines) in front and the Chinese were mostly called lu fei huaqiao (旅菲華僑). This older generation consider themselves sojourners (華僑): they are on temporary stays in the Philippines and desire to return to China.

That desire was crushed with Japan’s occupation of China, the Pacific War, and the 1949 communist regime of the People’s Republic of China which dropped the bamboo curtain to close off China’s borders.

After the war, nearly 90 percent of ethnic Chinese Filipinos were born, raised and educated in the Philippines. Organizations dropped the words lu fei (旅菲, sojourning in the Philippines) and adopted the words Fei Hua (菲華) or Filipino-Chinese: the identity is still Chinese but they happen to be in the Philippines.

Not until the 1960s did the new generation of Chinese Filipinos, who consider themselves Filipinos in identity but Chinese in racial origins, come about. They are the huaren (華人) and the huayi (華裔).

Many Chinese who migrated to Korea before the Ming (1368- 1644) and Qing (1644- 1911) dynasties did not settle down and form a community there.

The majority of Chinese in Korea today are still first- and second-generation migrants.

Up to 1992, Korea recognized Taiwan and Chinese Koreans were of mainly Taiwanese nationality.

There is, however, an original group of Chinese migrant huaqiao (華僑) from Shandong. The sharp political (allegiance to Taiwan vs. China) and ethnic divides (ethnic Koreans from Yanbian (延邊) and the huaqiao Taiwan nationals) weaken the communal identity as well as the political assertiveness and status of these Chinese Koreans.

The same political division – of allegiance to Taiwan or China – is likewise seen in the Philippines.

Although diplomatic relations with China was established back in 1975, the older-generation Chinese Filipino community – business groups in particular – was predominantly pro-Taiwan until the 1990s. Chinese schools and organizations were controlled and influenced by Taiwan.

In mid-1990s, China started aggressively “courting” community leaders and offered business opportunities in the mainland. Today, the political divide has blurred. The younger generation, however, are uninvolved and often unaware of the schism between the pro-Taiwan and pro-China factions. They are pro-Philippines and the issues and welfare of the Philippines and the Filipinos are their paramount concern.

This attitude is now increasingly evident in the younger Chinese Korean generation as well.

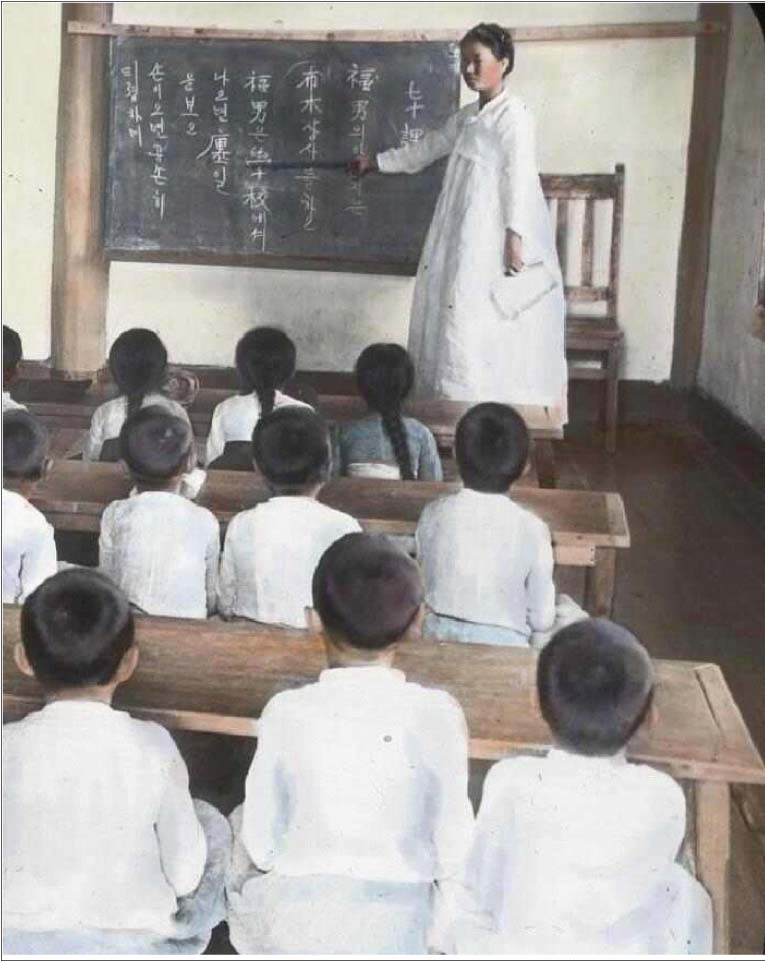

Chinese education

The first Chinese school in the Philippines – Anglo Chinese School – was established in 1899 to educate Chinese immigrants and give them the rudiments of English and bookkeeping to survive.

After World War II, the standard of Chinese education slowly deteriorated since there were no new immigrants after China closed its doors to the outside world in 1949.

Chinese-language education continued to deteriorate because the Chinese are a very small part of the Philippine population, when compared to Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore where there is a much larger Chinese population and greater demand for Chinese-language education.

In preparation for diplomatic relations with the PRC, then President Ferdinand Marcos issued wo presidential decrees – one in 1975 provided for easy access to naturalization through administrative process (against the older, expensive and lengthy judicial process); the other was P.D. 176, promulgated in 1973 to implement the constitutional provision on the Filipinization of all alien (read Chinese) schools. Up until then, Taiwan had a strong influence on the supervision and curriculum of Chinese schools.

Chinese schools had failed to strengthen the Chinese identity of the young Chinese. As well, the mass naturalization decree that gave them citizenship had far-reaching effects. These two factors moved the young-generation Chinese further in the continuum of deculturation. Many finished high school and went on to study in Filipino universities without needing to compete for limited admission based on racial origin.

Education of the ethnic Chinese in Korea, on the other hand, isolated them from the mainstream community. Huaqiao students are not allowed to enter regular Korean schools. When they finish huaqiao high school, they receive a graduation certificate from Taiwan’s government, so eventually they have to apply for the separate screening examination for Taiwan college entrance.

In the 1960s, there were more than 30,000 Chinese in Korea, a third of them, or 10,000, were students. All Chinese schools were established through efforts of the huaqiao. Today, there are four Chinese high schools and 29 grade schools in Korea with more than 3,000 students.

In the 1970s, graduates of Chinese high school were automatically accepted in Taiwan colleges. Today they have to pass the unified entrance examinations. About 50- 60 percent of Chinese high school graduates in Korea opt to study in Taiwan and the majority of these move to the U.S. or other countries.

In recent years, the number of students attending the Seoul Chinese Middle School has continuously declined because of remigration to other countries, increased attendance in Korean schools due to intermarriage with Koreans, and preference for education in Taiwan.

Since August 1999, however, the Seoul Chinese Middle School, along with two to three other schools, were legitimately recognized as “general schools” under the rigorous regulation by the Ministry of Education in Korea.

In the Korean educational system, very little preferential treatment was offered to the Chinese students. To enter Korean universities, Chinese students are screened separately from Korean students, resulting in extremely high competition between huaqiao applicants to enroll in private universities.

Languages

Generally, 98 percent of Chinese in the Philippines can speak Filipino or the Tagalog-based national language, 35 percent can speak another local major dialect and 90 percent can speak English.

Of first-generation Chinese immigrants, Hokkien is the lingua franca; even the Cantonese minority spoke Hokkien. Of the present generation, only 10 percent use Chinese as their first language.

Those below 30 years old speak Filipino and English, have limited Hokkien and Mandarin language abilities. This leads to concerns in the community over the deterioration of even the ability to understand Hokkien, much less Mandarin, which has no speech community to support its use.

Similarly, older generation Chinese Koreans speak the Shandong dialect in everyday life; while the younger generation speaks a mixture of Shandong, Korean and Mandarin, which is taught in school.

For those under 30, their first language is Korean. They learn Mandarin in school, and they are reportedly fast losing proficiency in the Shandong dialect.

Parallels in history

The Philippines had both trade and political relations with China before the Spanish occupation, which began in the 1500s. Chinese junks regularly visited the Philippines and envoys from the Philippines went to China to pay tribute to the Ming court. In the Ming Annals and the Tong Xi Yang Gao (Study of the Eastern and Western Oceans 1618), there are many pages of accounts mentioning islands or countries in the Philippines.

Korea has the earliest recorded arrival and settlement of the Chinese. History recounts that during the time of Zhou Wu Wang (周武王 1066 B.C.), 5,000 Chinese settled in Korea, spurring the area’s development. These 5,000 were the original huaqiao in Korea. This period of settlement is earlier than the Chinese arrival in any Southeast Asian country.

The early presence of the Chinese in Korea left indelible and far-reaching imprints on its civilization. Lasting influence in farming methods, burial grounds, language and writing methods, arts and culture like palace dances, ancient copper and bronze artifacts, jewelry and gold ornaments attest to these relations, which started before the Christian era.

In both Northeast and Southeast Asia, the Koreans were the first to be influenced by Confucianism, Buddhism and Chinese cultural enlightenment. The indelible imprints of Chinese civilization and culture persisted throughout several Korean monarchs’ reigns.

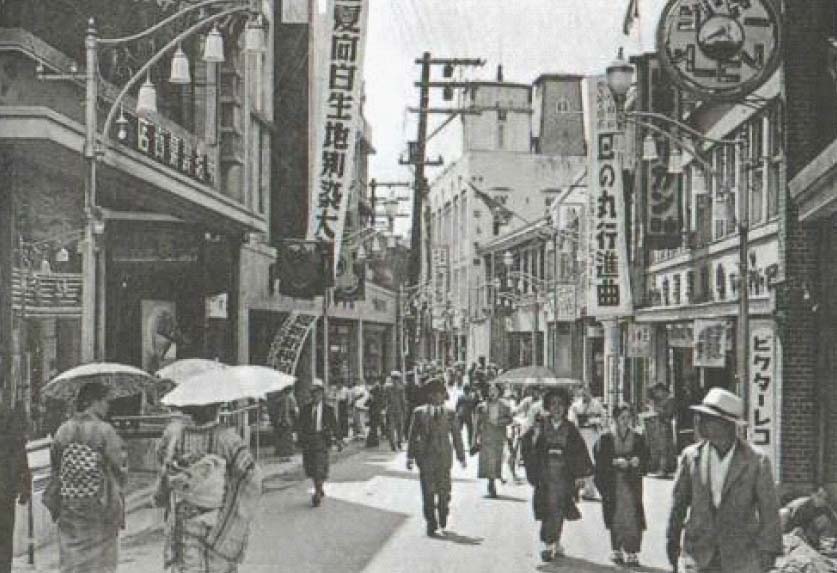

As with the Philippines, for centuries, Korea has inevitably been closely linked to China politically and economically because of geographical proximity between Shandong and Korea. In the late 19th century, the Chinese started to settle in Korea’s northeast.

Before the first Sino-Japanese War in 1894, Korea had been the most important vassal state to China. In the late 19th century, Chinese owned most of the larger shops in Incheon. Following Japan’s defeat in World War II, a new wave of Chinese immigrants into Korea began.

Not long after, refugees fleeing the Maoist regime moved to the Korean peninsula.

The different waves of out-migration from China to other parts of Southeast Asia, including the Philippines, coincided with periods of turmoil, unrest, drought, famine, and poverty that bred a general state of instability in the mainland.

The Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), Sino-Japanese War (1894) and Boxer Uprising (1899-1901) saw the biggest waves of migration to Southeast Asia, including the Philippines. In feudal China, peasants were forced to support the profligate lives of the Imperial Court through onerous levies and taxations, and thus suffered the most from these political unrests.

This period of migration experience to the Philippines and other Southeast Asian countries closely resemble that of the Chinese in Korea.

Shandong province is the origin of the Boxer Uprising. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Shandong was hard hit by famine, especially the northwest, causing many to leave. About 90 percent of Korea’s huaqiao are from Shandong.

Their reasons for immigration, like those of the early migrants to the Philippines, were: persecution by imperial powers; chronic poverty owing to high population density, and repeated natural disasters like flood and drought.

Integration and assimilation

At the turn of the 20th century, the increased repression and cruelty of the Spanish and American colonizers fostered a strong spirit of communalism among the Chinese in the Philippines.

Chinese institutions such as schools, the press, and other associations were set up as agencies of communal mobilization and cultural renewal. At the same time, the political awakening of the Chinese in China elicited a strong response from the local Chinese which further intensified their sense of nationalism.

After the Pacific War and the communist revolution in China, immigration to the Philippines came to a standstill and the local-born generation came about. Failure of Chinese schools to strengthen the Chinese identity of the Chinese youth, as well as the far-reaching effects of the mass naturalization decree that gave them citizenship, helped the younger-generation Chinese moved further in the continuum of deculturation.

Vast changes have taken place among these local-born people who make up 90 percent of the ethnic Chinese population in the Philippines. While the older Chinese still dominate leadership positions in the community, their number is quite small compared with the local-born younger generation. They are not only Chinese who are in the Philippines but have become Filipinos of Chinese descent who are a living part of the country, sinking their roots deeply into Filipino soil.

Meanwhile, in Korea during the 1970s, about 10,000 huaqiao left for third countries like the US, Canada, and Australia. Additionally, the number of huaqiao travelling abroad for such purposes as tourism, employment, and education increased dramatically. This phenomenon obviously showed the huaqiao’s despair of ever integrating into mainstream Korean society. Among those remigrating were leaders of Korea’s overseas Chinese community.

The kinship, village origins, and occupational networks of the huaqiao in Korea tied them together despite dispersal in many parts of Korea. These networks were crucial in maintaining the socialization and mutual support structure of the huaqiao. They highlighted the independence of the community and its isolation from mainstream society.In short, it provided a means of adaptation to the Korean social environment, one that emphasized the lack of integration and assimilation, especially if compared with the ethnic Chinese communities in other parts of Southeast Asia.

At the height of Korean nationalism, the huaqiao did not have many choices. They were forced to endure discrimination or else remigrate to third countries. However, after 1992, with the establishment of Sino-Korean diplomatic relations, the plight of the Chinese in Korea significantly improved.

Recent changes in Korean attitude and governmental policy show a new possibility of peaceful co-existence, moving towards integration. The younger generation is integrating into mainstream culture very rapidly. In school, huaqiao students speak Korean during recess and lunch time. More high school graduates choose to study in Korea colleges rather than go to Taiwan. Intermarriages between huaqiao and Koreans are also increasing.

However, huaqiao who have resided for generations in Korea and are fluent in Korean often simply blend in and hide their Chinese origins. Although officially the huaqiao are no longer subjected to open discrimination or maltreatment, the stigma of being “foreign” and the fear of rejection or exclusion prevent many from openly declaring their ethnic affiliation.

With Korean society becoming multi-ethnic and multicultural, Chinese Koreans can now find social solidarity and integration, especially those who have acquired citizenship by naturalization. Ethnic identity and nationalism based on blood ties and common culture apparently no longer foster a sense of belonging and solidarity among peoples of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

Post-war growth and modernization

The post-war period of Philippine nationalism saw the Chinese Filipinos’ merchant activities curtailed through nationalization measures. The newly independent Filipinos adopted the Filipino First Policy that nationalized many fields of endeavor held by Chinese Filipinos. This included the nationalization of retail trade, market stalls ownership, rice and corn trading, and the practice of all professions.

On top of this, the Philippine Constitution restricts land ownership and exploitation of natural resources only to Filipino citizens. This legislative fiat forced many Chinese to adopt Filipino citizenship, which hastened the process of political integration. The trade restrictions became a blessing in disguise. Chinese merchants moved from retail trading to manufacturing and exporting, pushing Philippine industrialization forward.

In the late 1970s, after the erstwhile alien Chinese obtained Filipino citizenship, many started to engage in big-scale agri-businesses such as fisheries, prawn-industry, piggeries, poultry raising, cattle raising and others. At the same time, they also became the importers of cheaper goods from China.

The ethnic Chinese were also successful in the banking industry. Chinese-Filipino-owned banks prospered. Integration of economic interests is inevitable because most of the businesses of the ethnic Chinese are domestic businesses where profits are plowed back into the Philippine economy.

These businesses are subjected to the same local laws and policies. They are sustained by Philippine economic growth or overwhelmed by Philippine adversities and calamities just like other sectors in the Philippine national economy.

China’s economic growth and development likewise have great impact on the Chinese-Filipino community. China’s investments in the Philippines are making great strides as do Chinese-Filipino businesses in China. Mining, construction and agriculture are the main focus of China’s investments.

In Korea as the 21st century began, significant legal reforms improved the status and made life easier for the Chinese there. The government recognizes the social realities of the Korean huaqiao in their midst and strives to tap their potential and networks for increased foreign investments.

Among these legislative measures are the amendments to the South Korean Nationality Law (2005), which made naturalization easier and accorded political and social rights for resident aliens; The Foreigners’ Property Ownership Act (1998) and Domicile Notification Act (2002).

Since June 1998, any foreigner or legal person can purchase real estate in Korea without discrimination. These legal reforms considerably improved the business climate for the huaqiao in Korea.

After the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the Korean government lifted or eased many regulations to attract foreign investors. This levelled the playing field for the Chinese overseas doing business with Koreans. Moreover, to revitalize its economy, the Korean government has invited ethnic Chinese investment.

Once diplomatic relationship with China was normalized in 1992, most Korean conglomerates, or Chaebols, were eager to break ground in the China market. Recently, some prominent and key positions in Korean conglomerates have been awarded to the Chinese.

Tourism is another booming industry. Chinese tourists from Taiwan, Hong Kong and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations are mostly handled by local travel agents in the Chinese community. Their linguistic advantages, networks and ethnic trust opened more opportunities for Korean huaqiao.

The economic rise of China gave Korea’s huaqiao another boost in their economic and political status. Many Koreans rushed to the mainland to open up new avenues for business and political connections. This happened at a time when Korean businesses struggled to seek new markets as Western markets declined.

These economic and political contacts with China provided the Chinese Korean community with increasing opportunities to bridge both parties. Diplomatic normalization since then has propelled the volume of Korean trade with China, making China her third largest trade partner.

These significant political developments brought about a slow but visible improvement in both the treatment and economic well-being of Chinese residents in Korea, which had hit an all-time low in 1976.

Recognition among Koreans of this new wealth and power among the Chinese have contributed to the mellowing of Korean attitude (at least official government attitude) towards the Chinese.

Contrasting consequences

Parallels in the historical, political and socio-cultural experiences of the ethnic Chinese in the Philippines and Korea – such as restrictive legislation, nationalization of ownership of property, limits placed on the practice of certain businesses and professions – impacted the two communities differently.

Restrictive legislation drove Chinese Filipinos to greater integration into mainstream society through the legislative fiat of acquiring citizenship.

In Korea, restrictive regulatory policies intensified the Chinese “sojourning attitude.”

The integration process is slow and happening only in recent years because the Chinese Koreans persist in considering themselves as huaqiao. They view Korea as a temporary workplace and refuge from poverty or political instability. Many huaqiao choose to escape from the oppressive policy toward foreigners by re-migrating to a third country.

Taiwan and its policy of accepting Chinese moving into Taiwan can be another reason for the relatively poor situation of the Chinese community in Korea. The Chinese Koreans did not strive for self-sufficiency in Korea because they had a better chance of going back home, a chance which was not given to Chinese Filipinos after the Pacific War and the Communist regime in PRC.

Having no choice but to sink their roots into Philippine soil, new generations born after the war have become vastly different from the older generation in their political orientation and identification with their native land, the Philippines.

The homogeneity and cultural isolationism of Korea did not encourage Chinese Koreans to take measures to be accepted into mainstream society. Their identification with China and Taiwan was their means for cultural survival.

In contrast, the Philippines, being a pluralistic and a Christian country made up of many indigenous and cultural minorities, has been very open and tolerant of minority groups and in accepting differing culture, practices, beliefs and traditions.

In short, more than culture and traditions, the success of integration and assimilation in the Philippines, as in Southeast Asia, allowed for the economic growth and development of the ethnic Chinese. On the other hand, Korea’s restrictive and isolationist policies hindered the integration and impeded the same growth and development.

As Korea gradually becomes a more open society, we may yet see opportunities for the economic success of Chinese Koreans. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 29, nos. 1-2 (June 21-July 4, 2016): 14-18.