Paleontology – the study of fossils, the remains and traces of past life – offers us a glimpse of the environment and evolution of the natural world from the distant past. Paleontologists assiduously search for fossil evidences, incorporating all available data from rocks and fossils in order to dig further into Earth’s history.

The oldest fossils date back 3.8 billion years. Majority of them are found in sedimentary deposits called lagerstatte. The Solnhofen Limestone in Germany and the Ediacara Hills in Australia are rich in well-preserved fossils. It is in Solnhofen that the iconic Archaeopteryx has been found.

Fossils also abound in Asia and China. Fossils have been discovered in localities such as Liaoning, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shanshan and Shandong, to name a few.

What is interesting is that some of these finds offer new insights that challenge previously accepted thinking. One fossil that has emerged as the new candidate for the world’s oldest bird is the Middle to Late Jurassic Aurornis xui. A group of paleontologists led by Pascal Godefroit found fossil specimens in the 160-million-year-old rocks of Tiaojishan Formation.

For more than a century, the Archaeopteryx of Germany was considered to be the oldest bird, but with the discovery of A. xui, the scientific community has been given a new perspective and a new frontier in exploration. In fact, this new discovery has supplied another piece of information – that despite A. xui and Archaeopteryx’s age gap of around 10 million years, with A. xui being older, the two are actually close relatives in the evolutionary tree of birds! Although A. xui is considered the world’s oldest bird for now, scientists continue to search for better and more conclusive evidence.

The complication arises in delineating between what is a bird and what is a winged and/or feathery dinosaur.

Archaeopteryx, Aurornis and other suspected early birds cannot be easily classified as stem-birds or stem-deinonychosaurs, says Thomas Holtz Jr., a paleontologist from the University of Maryland. One example of such feathered dinosaurs is found in China itself. This two-meter long relative of the velociraptor was uncovered in Liaoning province.

The Zhenyuanlong suni roamed the land about 125 million years ago when the first flowering plants dominated the forests. The fossil of this dinosaur was so well-preserved that its feathers can still be distinguished. The wings and feathers, however, may pose a misconception that this dinosaur had the ability to fly just like birds. They didn’t.

This is one question that scientists are trying to answer. Why did these dinosaurs need to develop such features? And how did the earliest birds eventually use them for flight?

Paleontologist Steve Brusatte of Edinburgh University said that the evolution took place for reasons other than flight. This brings back the question – what makes a bird a bird and what makes Aurornis different from winged dinosaurs?

In recent years, other species of the earliest birds were unearthed in other locations in China. In Dapingfang, Liaoning province, the skeleton of Chongmingia zhengi was discovered by the team of Dr. Wang Min of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

This recently published study in the journal Scientific Reports provides another clue to the early stage of development and evolution of the bird lineage. From its physical features, C. zhengi displays what researches consider as evolutionary experimentations, particularly on the ability to fly.

The genus name of this bird comes from the Mandarin word of a mythological bird Chongming, while the epithet was named after Xiaoting Zheng, one of the pillars of Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature. Joining Chongmingia is the 120-million-year-old, two-tailed Jeholornis. Jeholornis or the “Jehol bird” was first located in Hebei province and considered one of the largest among the earliest birds until the Late Cretaceous.

In a study led by Jingmai O’Connor of the Chinese Academy of Sciences based in Beijing, this species first appeared during the Early Cretaceous period and is described as having a “two-tail” plumage that is unique among the earliest birds. While the function of the second tail is still unknown, some paleontologists speculate it serves as an aid during flight or as a sexual display during courting.

Mark Norell of the New York-based American Museum of Natural History likened this feature to the colorful plumage of modern-day peacocks. Interestingly, birds, particularly the phoenix and its earthly counterpart peacock, have been considered symbols of fame, luck, dignity and beauty.

Other Mesozoic birds include Confuciusornis sanctus and Gansus yumenensis, both of which are also of great importance in deciphering the link between dinosaurs and birds and the emergence of the modern aves. Confuciusornis sanctus lived around 120 million years ago and is one of the evolutionary links between the dinosaurs and birds.

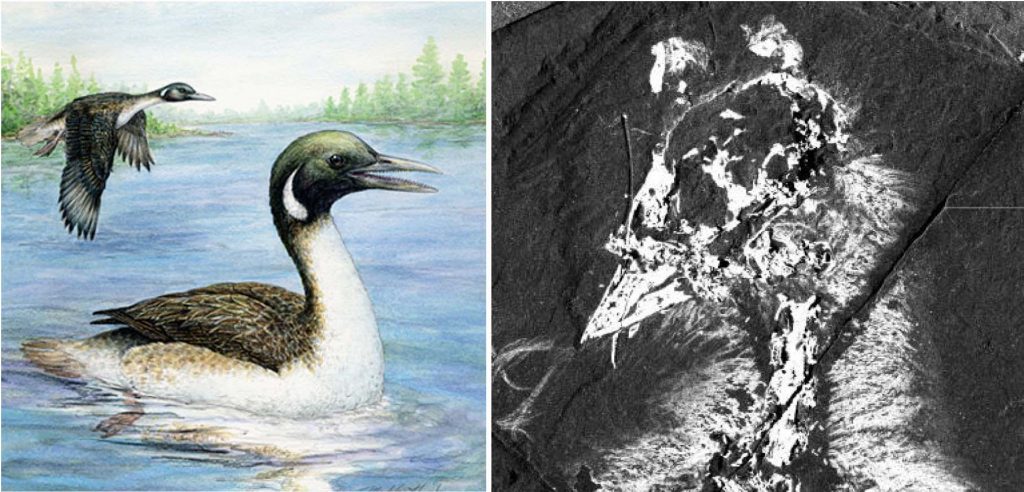

This species is distinguished from other basal birds since it is known to have the first bird-like beak. Aurornis xui in comparison had small triangular teeth. On the other hand, Gansus yumenensis are grebe-like birds that lived around 110 million years ago. Such specimens were exhumed in Changma town, Gansu province west of Beijing.

(Photo credits: Chuang Zhao. www.theguardian.com)

Matthew Lamanna of the Carnegie Natural History Museum pointed out the importance of Gansus in the evolution of birds since all living birds could probably have descended from a Gansus-like ancestor.

Aside from this, G. yumenensis revealed yet another noteworthy adaptation of the earliest fowls: from living on land to becoming water-dwellers and then reverting back to being land dwellers. Although fossils found in China have contributed to understanding the evolution of birds, much remains to be explored and studied, both in China and other parts of Asia.

Our very own fossils in the Philippines – including the Pleistocene rodents found in Callao Cave in northern Luzon and the Stegodon luzonensis, a relative of modern elephants – are examples of these paleontological treasures. Aside from the faunal assemblages found in China, flore such as the Late Pliocene peaches (Prunus kunmingensis) in Kunming province have been discovered by Dr. Tao Su of Xishuangbanna Tropical Garden and Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology.

With dedication and perseverance from both the scientific community and the general public, it is hoped that China and its neighbors, including the Philippines, can serve as a focus of this field of paleontology. And in return, contribute to a better understanding of our natural world and its history. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 28, no. 24 (May 24-June 20, 2016): 16, 14.