Evangelization, or the spread of Christianity, played a critical role in the colonization of the Philippines by the Spaniards. Unable to discover spices and gold in the islands, Spanish authorities had considered abandoning the colony. But the priests’ persuasion that the Philippines could be used as a stepping stone to propagate Christianity in China eventually convinced King Philip of Spain to maintain the colony. Bishop Domingo Salazar, for instance, suggested to the king, “What a glory to God it would be if we could convert the one million barbarian souls in Cathay.”

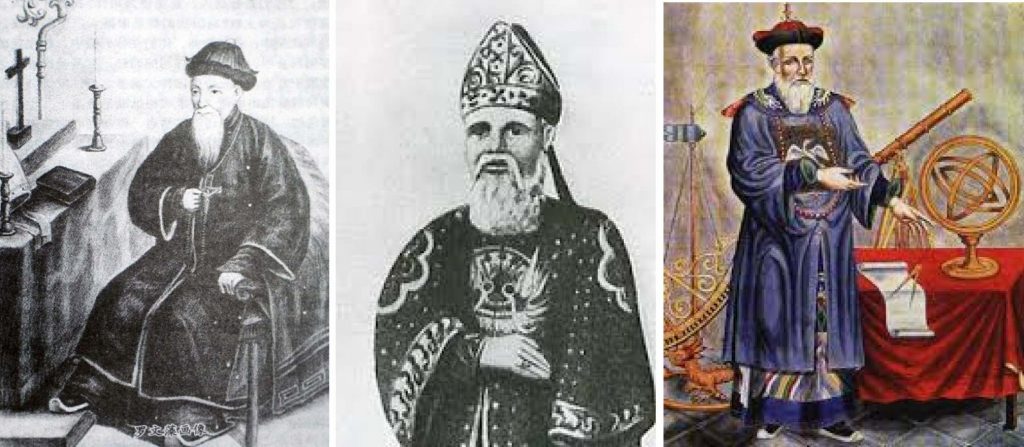

This colony played a great role evangelizing Chinese souls in China. The best example and evidence is that the first bishop of China, Luo Wenzao (羅文藻), or Gregorio Lopez, was ordained as a priest in Manila. He was a product of the oldest university in Asia, the University of Santo Tomas. Unfortunately, few people, even among the Catholic hierarchy, are aware of this fact. Luo (1615-1691) was not only the first bishop in China, but also the only bishop until the beginning of the 20th century.

Luo was born around 1615 in the village of Luojiaxiang (羅家巷) in the district of Fu’an (福安), Funing prefecture (福寧縣), Fujian province, from a local, non-Christian family. He was baptized by the Franciscan Antonio de Santa Maria Caballero in 1634, given the Christian name Gregorio and was employed by the missionary as one of the mocos, or young assistants. He may have traveled with Caballero and Francisco Diez, OP, to Taiwan in 1636, and may have returned to Fujian together with Father Gaspar Alenda and Brother Juan de San Marcos, OFM, in April or May of 1637.

In mid-June of 1637, he left the territory of Fujian with Franciscans Franciso de la Madre de Dios and Alenda and went to Beijing in an ill-fated expedition organized by the friars. The Franciscans had wanted the imperial court to stop the accusations from a Fu’an literatus against Christianity in the capital. Johann Adam Schall von Bell, a Jesuit priest, received the friars and three young assistants, including Luo.

Schall was an astromer tasked with finishing the modification of the Chinese calendar, including predictions of eclipses of the sun and the moon. Schall and his Christian literati viewed the the friars’ presence with hostility and saw it as a threat to the Catholic Mission in China.

The party was put under house arrest and eventually shipped back to Fujian. Meanwhile, a province-wide anti-Christian campaign erupted in Fujian and local authorities arrested Luo and a number of Fu’an Christians in November 1637. He was jailed in the Ningde district, then transferred to Fuzhou and finally expelled, together with the friars, to Macao.

From Macao, Luo sailed to Manila for the first time where he remained until mid-1640. He returned to Macao with another Dominican, Juan Bautista de Morales and Caballero. Luo remained as Caballero’s servant until Caballero and some Spanish nuns were forced to leave Macao on Oct. 9, 1644 following an order of expulsion of all Spanish from the Portuguese colony.

Luo followed Caballero in his journey. The ship, originally headed to Goa, shipwrecked in Cochinchina (Southern Vietnam). Local authorities saved Caballero and his party and brought them to the court of the Hue emperor. They were well-treated but apparently, Luo was considered a Chinese spy and risked execution. Finally in April 1645, they were all allowed to leave, arriving back in Manila on May 20, 1645.

Once back in Manila, through the intercession of Caballero, Luo entered the Dominican convent of Santo Domingo, where he learned to speak Spanish and read and write the Latin alphabet. Subsequently, he was admitted to the Colegio de Santo Tomas, not as a regular student but rather as an attendant, in order to be educated in Latin and humanities (which covers grammar and philosophy). He was promised admittance to the Dominican order in Manila, but before his formal admission, the Provincial Domingo Gonzales decided to send him back to Fu’an in mid-1647 to bring much needed funding to the missionary Juan Garcia.

Luo joined other friars in Dington, a coastal village near Fu’an, where he collaborated with the prominent local convert Guo Bangyong in building a large stone church in the Baroque style. In August 1649, he traveled to Xiamen to bring to Fu’an a new group of Dominicans who arrived from Manila, including Francisco Varo, who compiled the Chinese-Spanish dictionary.

On Jan. 1, 1650, Morales, now back in Fu’an, conferred on Luo the so-called “choir habit” for his services and virtue. It signals his formal admission into the Dominican order. On March 7, 1651, after one year in the novitiate in Dington, Luo took his solemn vows of profession. Thereafter, in the spring of 1652, he returned to Manila for a third time, to continue his theological studies at the University of Santo Tomas.

On July 4, 1654 he was ordained by the Archbishop of Manila, Miguel de Poblete, and was assigned to China by the provincial intermediate congregation of the Province of the Holy Rosary. Together with his confreres – Vittorio Riccio, Domingo Coronado, Diego Rodriguez and Raymundo del Valle – Luo reached China in July 1655.

He engaged in pastoral work in Fujian, enduring the consequences of the fighting between Qing Dynasty troops and Koxinga (a Ming Dynasty loyalist who defeated the Dutch East India Company on Formosa and spent the last 16 years of his life fighting against the Manchus/ Qing Dynasty), and the hardship of the coastal evacuation of Fujian ordered by the Manchu government.

During the anti-Christian campaign (1665-1670), most Dominicans were deported to Beijing and then to Guangzhou. Luo was in Quanzhou, where he could be undetected. In May 1665, he traveled to Manila for a fourth time to obtain funds for the mission, and brought back money not only for the Dominicans, but also for the Franciscans and Jesuits. He received orders from his superior to visit all the Christian communities of China since as a Chinese, he could go unnoticed by authorities.

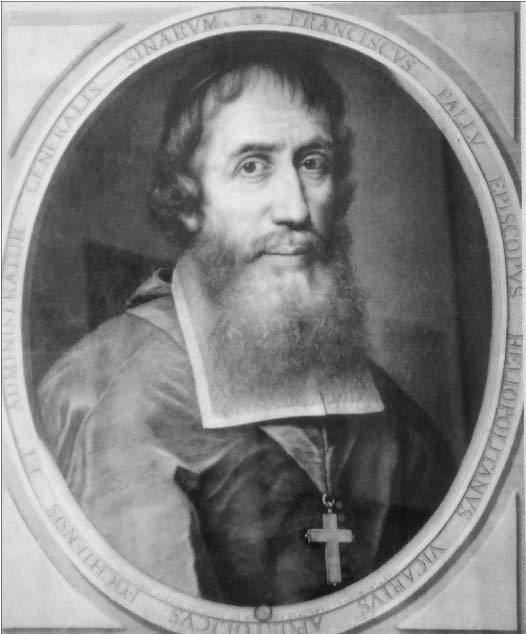

Luo traveled far and wide for three years, visiting communities in Zhili, Shandong, Shanxi and Shaanxi, Jiangsan, Jiangxi, Fujian, Zhejiang, Sichuan, Guangdong and Hunan. Luo’s fame soon reached the French Vicars Apostolic of China, Tonkin (northernmost Vietnam) and Cochinchina, who petitioned the Holy See to name Luo as Vicar Apostolic of northern China, and to consecrate him as a bishop.

Domingo Navarrete OP, who had been initially chosen for that position, strongly recommended Luo for Propaganda Fide (Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith), and in 1673, Luo was made the first Chinese Catholic bishop of China.

On Jan. 4, 1674, Pope Clement X named him Bishop of Basilinopolis, Vicar Apostolic of Nanjing and Apostolic Administrator of five other northern Chinese provinces and of Korea. His ordination should have occurred in Siam, where other bishops were available to ordain him. However, partly due to the opposition of some of his Dominican confreres, especially Francisco Varo and partly due to his own doubts, Luo first refused the nomination.

Varo, for example, thought that Luo did not have the necessary theological background to deal with the delicate problems of jurisdiction and the “Chinese rites” (dispute among Catholic missionaries over whether Confucianism and Chinese traditions like ancestral rites are incompatible with Catholic beliefs), then a raging controversy.

Luo endured years of diatribes, but the French Vicars Apostolic and the Holy See insisted on the ordination. In October 1679, Pope Innocence X confirmed his will to have Luo ordained. Luo received the papal letter in 1681, and could not ignore the orders any longer. At the same time, the Dominican superiors asked the Holy See to name a theological adviser for Luo to give him assistance in his new ministry.

Luo decided to travel to Manila again to be consecrated, and after many difficulties, he finally made his fifth landing in the Philippines in 1683. But the Spanish ecclesiastical and civil authorities were against his ordination, which they considered an encroachment of the papacy over the missionary Patronato Real (Royal Patronage) of Spain.

Racial consideration probably also played a role in strengthening the opposition of Luo’s Dominican superior in Manila. Moreover, Luo had only received a short education in theology and philosophy, and had shown a tolerant attitude towards “Chinese rites,” which was opposed by most Dominicans, but is close to the Jesuit and Franciscan positions. In fact, the Manila Jesuits translated into Spanish a conciliatory treatise on the rites Luo had written in Chinese.

Luo remained in the Chinese parish of the Parian in Manila for a year without receiving consecration. He sent a circular letter, to all the China missionaries denouncing the situation, and repeatedly wrote to the Pope and King of Spain to try to resolve the situation. Luo eventually became enmeshed in jurisdictional struggles between the civil and ecclesiastical authorities of Manila, and so with the help of Diego Calderón y Serrano, auditor in the Royal Audiencia of Manila, he escaped from the Dominican parish and finally left Manila for China in 1684.

He returned to Fu’an, hoping to be consecrated by the French Vicar Apostolic Francois Pallu, but when he arrived in Pallu’s mission of Muyang (near Fu’an), he discovered that the Vicar had recently died.

Luo’s odyssey ended when he received a letter from Vicar Apolostolic Bernardino Della Chiesa, OFM, who invited him to Guangzhou to be consecrated. Luo traveled with Pallu’s confrere, Bishop Charles Maigrot MEP, to Guangzhou, and was finally consecrated on Apr. 8, 1685.

Luo, assisted in his work by the Italian Franciscan, Francesco Nicolai de Leonissa, reached Nanjing on June 30, 1685. He was received with great jubilation by local Christians. He soon started a visitation of his vast vicariate. He also had the satisfaction of ordaining, in 1688, three Chinese Jesuit priests, among them the famous painter, Wu Li (吳歷).

In Spring 1690, to appease the Portuguese government, the Holy See agreed to elevate Nanjing into a diocese under the Portuguese Padroado, and Luo was named its first bishop, with Lemissa as his Vicar General.

Luo died in Nanjing on Feb. 27, 1691 after a short illness.

Luo’s story shows how closely linked China and the Philippines were, especially in relation to the spread of Christianity. Luo came to Manila five times between 1638 to 1684, he was ordained in Manila, studied Theology at the University of Sto. Tomas.

In his fifth and last year-long visit to Manila, he stayed in the Chinese parish of the Parian and must have made many Chinese Catholic friends and became well-known among compatriots living there.

Luo’s conciliatory treatise on Chinese rites translated to Spanish by Manila’s Jesuits is undoubtedly an important document in the ecclesiastical history of the Philippines.

Where the document can be found and who were the Jesuits capable of translating Chinese to Spanish in the 17th century are subjects which we hope trained historians can help research.

(Most of the information on Bishop Luo Wenzao are taken from a compilation by Menegon, Eugenio https://www.academia.edu/23057333/Luo_Wenzao (羅文藻) Gregorio Lopez OP_1615-91 and sourced from Gonzales, Jose, Maria OP. El Primer Obispo Chino, Fray Gregorio Lo a Lopez, OP, Villava, Pamplona, 1966.) — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 28, no. 24 (May 24-June 20

, 2016): 8-10.