The Philippines in Selden Map 《東西洋航海圖》(Tulay, April 5-18, 2016 issue) article described the importance of the Philippines as China’s connection to the world in its ancient maritime silk route. The map’s origins – who drew it up and who had commissioned it – is a puzzle that historians are still trying to decipher.

We had highlighted the fact that the places in the map, especially those in the Philippines, are in Hokkien. And the Chinese characters were those commonly used and known to the Chinese in the Philippines. Examples are Tua Kang (大港) to refer to Aparri, Ong Sia (王城) to refer to Intramuros and Hua Lang (化人) to refer to Spaniards.

Robert Batchelor and other Chinese scholars who studied the map extensively theorize that the map belonged to a Hokkien merchant in the Philippines. Specifically, they speculate that it was Li Dan (李旦 ?-1625), a well-known Hokkien merchant with vast networks in Southeast Asia, Taiwan and Japan, who commissioned the drawing of the map.

Li Dan was a trader based in Manila who later moved to Hirado and Nagasaki in Japan. There are a number of Chinese, Japanese and Dutch sources about Li Dan (foreign name Andrea Dittis) and his background, but they have little information about the Philippines and his Manila networks and activities.

The 55-volume Blair and Robertson’s The Philippine Islands (1493-1898) and other authoritative history books and accounts on the Philippines have no mention of Li Dan at all. We first encountered the mention of Li Dan in Sterling Seagrave’s 1995 book, Lords of the Rim.

The book claimed that the 1603 massacre of the Chinese was caused by Li Dan, the leader of the Chinese community then, but this information has never been mentioned in any Philippine history book. Seagrave said Li Dan escaped to Japan after the Spaniards detained his ship. Unfortunately, Seagrave did not cite any references regarding this event.

Fortunately, University of Hong Kong History professor Dr. James Chin’s article, “Junk Trade, Business Networks, and Sojourning Communities: Hokkien Merchants in Early Maritime Asia,” help give some basis for Seagrave’s claim: “The diary of Richard Cocks and the detailed archival records of the English East India Company factory at Hirado from 1613 to 1623 give us a fragmentary but fascinating picture of this Hokkien Captain. In a letter sent to the East India Company dated 25th February 1615: (quoted verbatim, bracketed questions from Chin —Ed.) ‘These 2 China brothers, Andrea Dittis & Whaw, are great merchants & will contynewally [bring more?] merchandiz in this place then all the Japons in Firando. Andrea Dittis was governor of the Chinas at Manilla in the Phillippinas and in the end the Spaniardes picked a quarrell on purpose to seize all he had, to the vallew of above 40,000 taies, [and put him?] into the gallis, from whence he escaped som 9 years since & came to Firando, where he hath lived ever since.’”

Chin further writes: It can be inferred that “Li Dan had been a very rich merchant and was the governor or leader in the Hokkien community of Manila before he escaped from the Spanish galleys in 1606, soon after the first Chinese massacre of 1603 in Manila. It also seemed that Li Dan established himself at Hirado very quickly, and regained his influence among his fellow countrymen within a few years.”

Xiamen University historian Zhou Yunzhong wrote about the British ship The Elizabeth capturing a Japanese boat in August 1620. The captain, Diego Fernandez, and two Spanish friars, Pedro Manrique De Zuñiga and Luis Flores, said that the owner of the goods found in the boat was a Chinese trader called Li Dan.

The Selden Map, which they believed belonged to Li Dan, surfaced then and researchers theorized that it was among the goods forcibly taken by the British ship. The most number of identified places in the Selden Map were Luzon, Vietnam and Japan, hence the speculation that the boat owner and map owner was Li Dan.

Li Dan owned a big fleet of ships that sailed all over the region, especially Southeast Asia and Japan. He even helped England establish trading networks in Nagasaki and garnered huge investments from Great Britain.

Chin also wrote about Li Dan’s Dutch connections: “For the next two years (1622 to 1623 —Ed.), the Dutch tried very hard to force the Chinese authorities to open up trade but failed, until the prominent Hokkien merchant leader Andrea Dittis or Li Dan based in Quanzhou came to the Pescadores in August 1624 and volunteered to be the broker in the negotiations between the Dutch and the Fujian authorities.”

It was not just Fujian authorities with whom Li Dan had deep connections but also Japanese feudal lords.

Chin writes: “What he invested in the forging of special relations with these feudal lords was rewarded generously. In return for Li Dan’s gifts and generosity, Matsuura Takanobu not only helped him to obtain the license for overseas trade from the Shogun at Edo, but also succeeded in securing for him the monopoly in trading with Taiwan.”

We have asked our Chinese historian friends to help us search for more sources on Li Dan and the Philippines, especially on confirming or refuting Seagrave’s claim that Li Dan was the leader of the Chinese community during the 1603 massacre and that he moved to Nagasaki as a result. There is a more intriguing story about Eng Kang, the leader of the 1603 revolt.

Lucille Chia, in her book The Butcher, the Baker, and the Carpenter: Chinese Sojourners in The Spanish Philippines and Their Impact on Southern Fujian (Sixteenth-Eighteenth Centuries), writes: “A Christian Chinese who was the head Chinese official (gobernadorcillo) of the Chinese quarters (Parián) in 1603, with a Chinese name transcribed as Encang, had the Hispanic name of Juan Bautista de Vera. Encang ended up as one of the leaders of the 1603 ‘rebellion’ and massacre of the Chinese.”

Is it possible that Li Dan was in fact Encang or Juan Bautista de Vera. Encang was hanged and quartered after the 1603 massacre. Could it be possible that the one who died was a scapegoat to allow the rich and well-connected Li Dan to escape? This is historical speculation that needs further study.

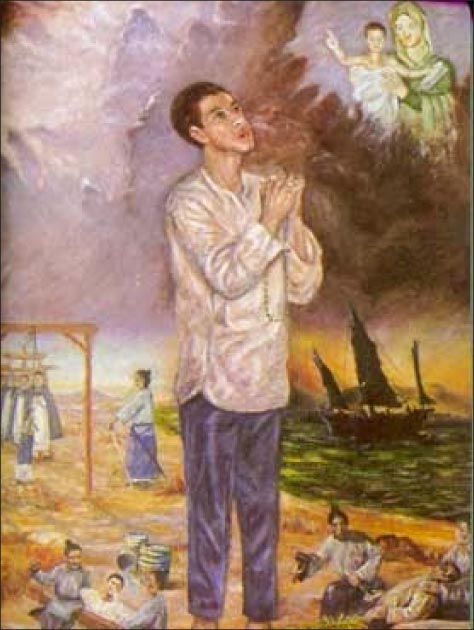

In addition, Li Dan had a daughter Ignacia (baptized as Elizabeth) and a grandson (child of his son Agustin) who were burned at stake (火刑) in Nagasaki in 1635. Our first Filipino saint Lorenzo Ruiz’s Chinese surname is Li. Ruiz escaped with the Dominican friars to Nagasaki and died a martyr there in 1637. Ruiz was an escribano (clerk) for the Dominicans, which indicated a good learning background and that he must have come from quite a prominent family. Is there a connection between Li Dan and Lorenzo Ruiz?

This is certainly another matter worth exploring. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 28, no. 23 (May 10-23, 2016): 8-9 under the original title “16th century networks beyond China’s empire.”