First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest | November 1-14, 2016 | vol. 29 | No. 11 |

The vast necropolis in the north of Manila’s Sta. Cruz district, consisting of the North, La Loma and Chinese cemeteries, is a veritable museum to the evolution of Western and Chinese architectural styles and their adaptation and transformation in the Philippines over the past 150 years. Among them, the Manila Chinese Cemetery is an important repository of the evolution of the Chinese in the Philippines and their ultimate transformation from immigrants to today’s “Tsinoys.”

Initiated in 1843, the multi-denominational cemetery was founded or enlarged in 1863 by Lim Ong, gobernadorcillo of the Chinese community in Binondo. Owned and managed by the Philippine-Chinese Charitable Association, it was substantially enlarged in 1878 and again in the 1950s.

With the constant redevelopment of Binondo and San Nicolas, Manila’s original “Chinatown,” and the ceaseless demolition of their historic buildings in the name of “progress” and profitability, it is the cemetery which bears witness to centuries of migration, persecution, struggle, and ultimate integration of the Chinese community.

Cemeteries the world over reflect the identity, values and beliefs of a society, its history, evolution and achievements, as well as social and racial/ethnic stratification. As such, the Manila Chinese Cemetery illustrates what characterizes the Tsinoy community: its widespread religious syncretism and cultural hybridism and adaptability.

Far from merely copying western models of art and architecture, the builders of these tombs and mausoleums merged Western and Chinese building traditions into a unique hybrid architecture, a synthesis of East and West characteristic of Tsinoy material and non-material culture.

19th century changes

The fine mausoleums and tombs at the North, La Loma, and Chinese cemeteries are the product of revolutionary changes in European cemetery design in the early 19th century.

Municipal-owned and secular, these new, carefully laid out and landscaped garden cemeteries were established at the periphery of the rapidly growing industrial cities. Plots here could be bought or leased long-term, thus enabling personal commemoration and erection of individual tombs and mausoleums.

With them came a new way of seeing death itself, not as a grizzly end, but merely a temporary separation of the deceased from his loved ones, resulting in a veritable death cult celebrating the “Beautiful Death” through art, statuary and architecture.

The oldest tombs still found in the Manila Chinese Cemetery today resemble those in colonial-era churches: large granite or marble slabs engraved with the name, place of origin, and life dates of the deceased, but now mounted on an above-ground sarcophagus set in the midst of a small fenced plot (e.g. tomb of Pilar Tiaoqui de Lim-Tuaco from 1895).

The need to protect visitors at the gravesite during the Qingming festival or All Souls Day from the harsh tropical climate of sizzling sunshine and torrential rain soon led to tombs covered with roofs, as seen in the 1900s tomb of Tiu, an immigrant from Kaiping, Guangdong or Canton. Her sepulcher’s simple roof is carried by calados (pierced fretwork) typical of the bahay na bato, the traditional Hispanic-Filipino house.

Roofs soon proliferated, giving rise to a distinct mausoleum culture markedly distinct from Chinese cemeteries in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand where large Chinese communities also exist.

Revivalism

Emerging in the 18th and 19th centuries, popular revivalist styles in Europe and North America found their way to the Philippines in the late 19th century. Here, their adaptation for funerary architecture sparked a wave of exquisite tombs and mausoleums in the early decades of the previous century.

First among the revivalist styles was Neo-Classicism, which emerged in the mid-18th century as a rational and sober style based on Greco-Roman models in response to the Baroque’s exuberant and theatrical decadence. Because of its association with Greek democracy and Roman republicanism, it easily became the dominant style of public and educational architecture of the USA and in extension, of the Philippines.

The style employs the architectural vocabulary of classic antiquity exemplified by the Sy Mausoleum, which is reminiscent of a Greek temple in a somewhat modernist interpretation. An interesting Neo-Palladian version can be seen in the Tambunting Mausoleum just outside the Chinese Cemetery. In contrast to “progressive” Neo-Classicism is “conservative” Neo-Gothic, a revival of the great medieval Gothic, which became immensely popular in 19th century Europe and North America.

A romantic reaction to de-humanizing industrialization, espousing mysticism and spirituality, it naturally lent itself to funerary architecture and quickly became a preferred style in the grand 19th-century cemeteries of Europe and the U.S.A., and thence the Philippines. A good example is the 1920s Dijiongco Mausoleum which employs the style’s classic repertoire of spires, crabs, and gargoyles.

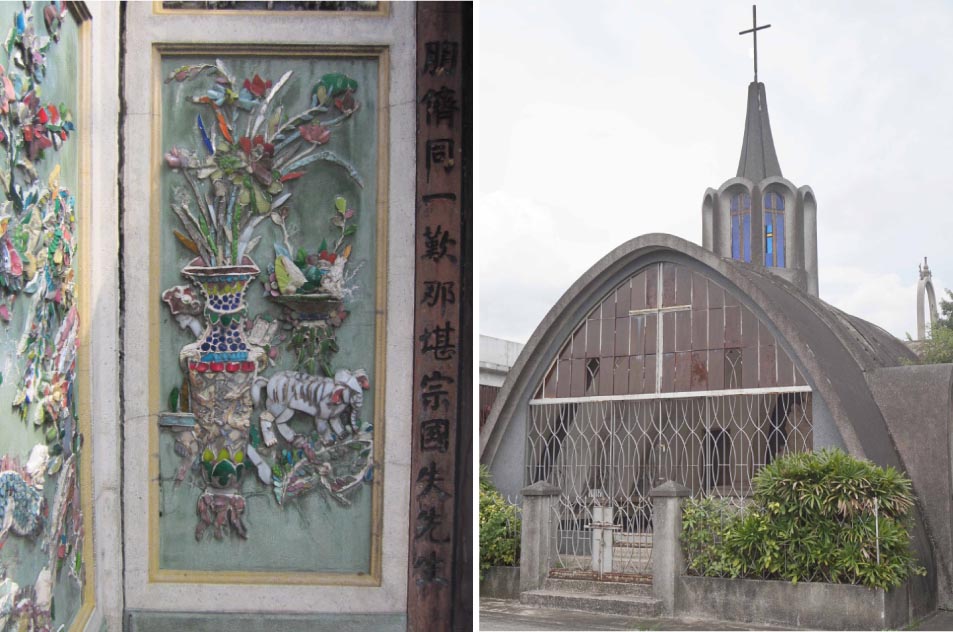

Typical of the hybridism that characterizes Tsinoy culture and architecture, some 1930s mausoleums (Machuca-Gotanco, Benching) artfully combine classic Gothic elements like lancet arches with Chinese ones such as guardian Foo Dogs, jiannian cutworks and medallions depicting birds, dragons and trees.

Art Deco

The end of the old world order after World War I spawned revolutionary and comprehensive social transformations which sought not only a new and more equitable society, but also a new contemporary and democratic architecture, giving rise to Modernism and Art Deco during the inter-war period.

Art Deco’s iconography embodies and celebrates the rapid technological progress of the dawning machine age.

Employing a wide range of new, industrially made and mass-manufactured materials such as chrome and plastics, Art Deco’s ornamentation resembles machine-made objects: sharp angles and contours, large plain unadorned surfaces, dramatic volumes, bright and bold colors, and profuse abstraction.

Typical elements of Art Deco’s Zigzag Moderne version are chevrons, frozen fountains, zigzags, triangles, hexagons, sunbursts, sunflowers, nautilus shells and spirals, as seen in the beautiful 1930 Dy Buncio Mausoleum. With the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen in 1922, Egyptian funerary architecture became immensely popular. For example, the 1948 Li Chay Too Mausoleum was modeled after an Egyptian temple.

Inspired by foreign and “exotic” cultures, Art Deco easily appropriated classic Chinese design motifs, as evident in the 1938 mausoleum of Lim Kong Sui, which is crowned by a stylized dougong, reminiscent of traditional Chinese roofs. In contrast, Art Deco’s Streamline Moderne in the 1930s emphasizes streamlining and celebrates the age of speed: racing cars and trains, transatlantic flights, and ocean liners, expressed in speed stripes, horizontal grooves, rounded corners, and plain unadorned surfaces of white or monochrome colors, not only in architecture and furniture, but even in mundane objects. The 1940 Go-Sun Mausoleum is an excellent example.

Modernism

Following the devastations of World War II, Modernism presented not only a fast and cheap way of reconstruction in line with the necessary frugality of the times, but also offered an alternative narrative disconnected from the traumas of colonialism, occupation and war, promising a brave new world.

Emerging in early 20th-century Europe and North America as a socialist-utopian reaction to the ‘facadism’ of Revivalism, it

pursued a more egalitarian society, completely breaking with past and vernacular traditions. Modernism proposed globally-valid solutions for urban planning and architecture based on universal credos such as “Ornament is Crime,” “Form follows Function” and “Less is More.” Its emphasis on structural visibility, natural quality of materials, and straightforward design is best exemplified by the Saez-Coguanco Mausoleum, and the Tan Tiong Mausoleum for its Tropical Modernism variant.

Chinese elements were easily incorporated into Modernist base concepts, such as stylized dougong roofs or buildings solely composed of stylized Chinese characters such as the Lin Mausoleum. With rapid technological progress such as nuclear technology and space travel, in the 1950s and 1960s “progress” seemed unstoppable, promising an immensely optimistic future of endless possibilities.

Architecture took its cue from these technologies and translated them into a new, dynamic and exciting design vocabulary such as paraboloids, ultra-thin concrete shells, folded plates, and biomorphic forms. These elements also found their way into funerary design, as apparent by a number of highly dynamic and soaring mausoleums in the newer portion of the Chinese Cemetery.

Post-modernism

By the 1970s and 1980s, the failure of many postwar utopias (communism, progress and others) led to re-orientation, socially and architecturally. With Modernism increasingly seen as banal, monotonous and de-humanizing, the ornament made a glorious comeback. Undogmatic, loud, and colorful, Post-Modernism proclaims plurality and artistic freedom, freely and playfully mixing past style’s forms and elements.

In the Philippines with its horror vacui and penchant for decoration, Post-Modernism quickly became popular, as seen in many over-decorated mausoleums in the newest portions of the Chinese Cemetery.

Chinese styles

Not surprisingly, a great number of mausoleums adhere to traditional Chinese architecture, which dates back several millenia and is primarily guided by feng shui principles. Rooted in the belief that the divine manifests in the material world, feng shui emphasizes balance and harmony which reflect the natural hierarchical cosmic order. Thus, symbolism (colors, lucky numbers), cardinal directions, orientation and the flow of Chi energy, are of immense importance.

The dominant architectural element is the often multi-tiered roof with dynamically sweeping curves and upbent ridges carried by wooden corbels (dougong). Roofs are typically richly decorated with ceramics depicting plants, dragons, birds, and other animals, while guardian lions (Foo Dogs) protect important entrances.

The basic principles of traditional Chinese architecture and feng shui have been adapted to funerary architecture (now executed in concrete rather than wood) as evident in a number of courtyard mausoleums in the Manila Chinese Cemetery.

The Ongche Mausoleum (ca. 1936) is a classic example of the emphasis on symmetry and axiality in traditional Chinese architecture, providing a processional route from the entrance gate to an open pavillion in the center of the structure and on to enclosed burial chamber at the end, passing two landscaped courtyards en route.

Also commonly found are pagoda-style tombs, such as the Dy Her Chan Mausoleum from about 1933 with its three-tiered roof over a square footprint characteristic of older historic pagodas in China. One of the cemetery’s largest is the Yu Chu (Regal) Mausoleum, a massive postwar structure in the newer part of the cemetery.

An interesting combination of the pagoda-style with Art Deco can be observed in the 1941 mausoleum of Dee Ching Chuan, co-founder of China Bank, where a massive tower with Art Deco-typical massing and window treatment combines with traditional Chinese elements and motifs, such as a curved tile roof and a series of terraces in the forecourt, which, together with the intricate details and interior murals, bear strong associations to Imperial China.

Rare are the turtleback tombs, which in other parts of Southeast Asia form a mainstay of Chinese diaspora cemeteries. Originating in South Fujian province, these unroofed burial mounds in the shape of a tortoise back symbolize longevity and the shape of the Chinese cosmos.

Yet, in line with Tsinoy religious syncretism, even these quintessential “Chinese” tombs have been subject to cultural adaptations, as manifest by the 1950s Go Mausoleum, where a complete Neo-Baroque basilica with Greco-Roman and Moorish details is super-imposed on a traditional turtle tomb.

With the vast majority of Philippine Chinese migrants coming from South Fujian, it was the style of this province with its characteristic swallowtail roof often adopted for funerary architecture, as can be seen in the 1940 Basa Mausoleum, reminiscent of a 19th century South Fujian Temple, and the Chong Hock Temple from 1878, the oldest such structure in the Philippines (demolished 2015).

The former, as many other mausoleums, sports elaborate jiannin mosaics, colorful ceramic cutworks showing plants, animals, and humans. The latter, a combination of Chinese temple and Catholic chapel where Christian, Taoist and Buddhist images are venerated and ancestors are commemorated all under the same roof, is a good example of the syncretism that so characterizes many Tsinoy religious beliefs.

Such syncretism is facilitated by many communalities between Chinese polytheism and Roman Catholicism, such as the belief in an afterlife; certain rituals during religious holidays (All Souls Day, Qingming Festival); similarities between the Catholic Mother Mary and the Chinese goddesses Ma Tzu and Guan Yin, and the intercession of saints and deities in heaven, apart from pre-Christian beliefs in spirits and superstition.

Blending of spiritual worlds

For the Spanish during their 333 years of colonial rule in the Philippines, conversion of the natives to the Catholic faith was a primary goal, which opened personal and business opportunities denied to “infidels.” Hence, Filipino tolerance, Chinese pragmatism, and systematic missionary efforts resulted in the conversions of many Chinese immigrants and subsequently in the blending of the spiritual worlds of East and West.

The desire of immigrants to blend socially, politically and economically into their host society, and a colonial policy that actually encouraged interracial marriages together with religious conversion spawned many mixed marriages, leading to the emergence in the 18th and their social and economic rise in the 19th century of a wealthy and educated mestizo elite (Ilustrados) of combined Chinese, Malay and Spanish ancestry.

Thoroughly hispanized and devoutly Catholic, this group later merged with wealthy Chinese and Spanish mestizos into the first “Filipinos” and still forms the country’s elite. With a tendency towards ostentatious display of wealth already apparent during the Spanish era, the introduction of (limited) participatory democracy under the Americans opened up positions of political power and influence for them.

With the simultaneous entree of the garden cemetery culture, their newfound status soon found expression in elaborate tombs and mausoleums, designed initially by Western architects, and from the 1910s onwards increasingly by western-trained second-generation Filipino architects such as Pablo Antonio, Juan Nakpil, and Andres Luna de San Pedro.

With ever less available land and stiff competition from now-en-vogue inner-city columbaria and suburban memorial parks, the days of grand mausoleums may ultimately be numbered. However, with the ongoing out-migration of Manila’s elite and middle class to the surrounding suburbs, many old families decided to have their ancestors exhumed and transferred as well, causing many fine mausoleums to now stand empty and abandoned.

Hopefully, this important heritage will soon be recognized and protected, for these tombs are witness to and evidence of the Tsinoy’s firm rootedness in Philippine soil.