In January, Celine Medina and I planned a shoot around the female gaze. Celine is a photographer who I met on Twitter. She had placed an open call for collaborations, so I responded. We then followed each other on Twitter and expressed our mutual desire to work together.

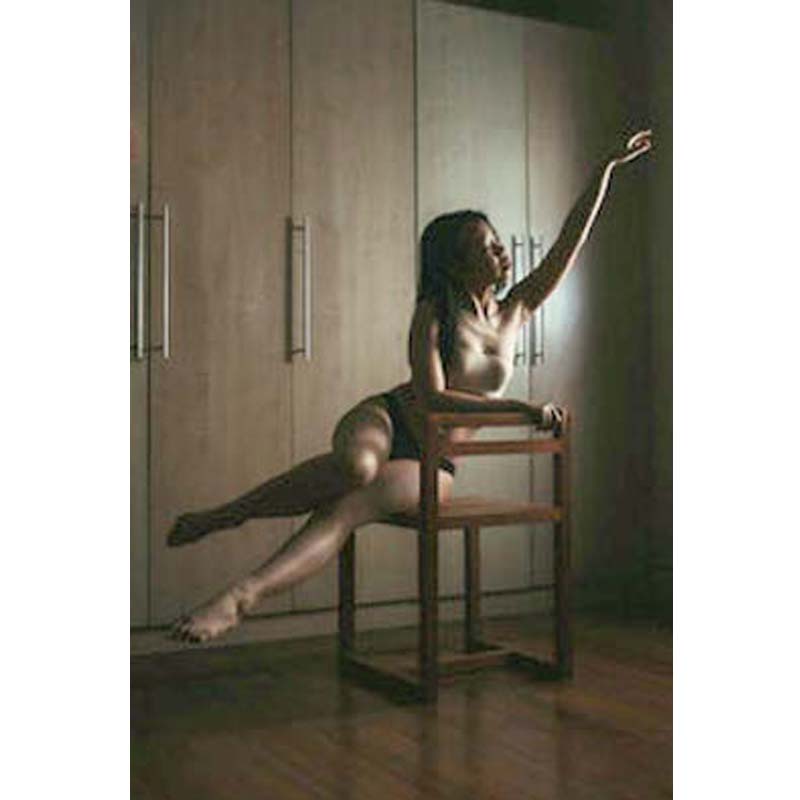

We finally met on Feb. 17 to shoot at my house. We decided to focus on body scapes, in particular, the shapes my body could form through movement. Our shoot was collaborative. I came up with poses and Celine observed me through her lens. She hardly gave instructions, I was free to do as I liked.

We wanted to shoot body scapes because we wanted to explore the female gaze, the gaze of women, both image-makers and viewers. Historically, most images have been actively created and viewed by the Christian heterosexual male, with women being structurally relegated to passive viewers and subjects.

Therefore, it was important for us to share our gaze as female artists to make up for lost time. The shoot was also an avenue to explore Celine’s Twitter question, “Is there even a legitimate way for a woman to reclaim her sexuality without being accused of catering to the male gaze and patriarchy?”

I had not answered the question when I got the photos. I thought I looked sensual rather than sexual. I liked how toned and muscular I looked. I have gotten curvier since the last time I did something like this, and embracing my new body has been a struggle, but seeing it close up and curved in shapes helped reconcile my relationship with my image.

Celine released the set of photos on her social media accounts. Since then, I have had an influx of male photographers adding me on Facebook and Instagram. Honestly, they did not add me because they admired my body of work, but rather because they saw a woman’s body, they were not there for the artistic merits of my modelling.

I was pandering to their taste of what is erotic. None of the people who added me were female. A photographer that had previously expressed his keenness to collaborate with me but left me in the lurch when I turned down a nude shoot resurfaced on messenger hoping for a shoot with me again. This experience is not unique, it is quite common among models. I blocked him before he had the chance to ask again.

Every now and then people feel the need to tell me, “If you don’t want creeps on your socials, don’t post provocative photos,” and it irks me to my core because the problem is not my photos. I do not feel that my photos are erotic. My best friend feels similarly. Those who see my photos as sexual material and act as creeps are responsible for themselves. They can control themselves, but they just choose not to. The message we send to women is that they are simultaneously victims and perpetrators when we keep telling them to cover up.

I am a feminist, but I have not known a world that is not defined by patriarchy. I still am one of many generations raised on a steady diet of female nudity and sexuality defined by male image-makers, i.e. painters, photographers and directors.

Movies I consumed focused on slim women’s curves and emphasized their subservient eyes. To answer the Twitter question, it is difficult to reclaim my sexuality without being accused of catering to men because this is almost all I have ever known.

Women are more than erotic objects, we have more diverse identities than male image-makers are presenting. We must seek and demand films directed by women. Watching films for and by women will enable us to see women through different lenses and roles.

Real women can be maternal, strong, feminine and adaptable. They come in different skin colors, ages and body types. Often, women in film are portrayed as white, slim and under 30, after which they are cast as mothers or witches. This is a small demographic category of all women living in the world. We must, therefore, consume more women-led content in the media.

Men will never know what it is like to be women. That phenomenon is unique to us and no one can express it more accurately or better than we can. Going back again to the Twitter question, why is the basis of the legitimacy of my reclamation bound to the male gaze? We should be asking questions that prioritize the perspective and opinions of women. Does this image cater to the female gaze? Does this add to the diverse representations of women? Does this content make women feel empowered? Photography is still overwhelmingly male, so it is even more important for female creators, such as Celine and I, to occupy space and make art nuanced by our experiences and perspectives.