My mother and her parents were imprisoned in the Santo Tomas Internment Camp during World War II for three years, one month and three days.

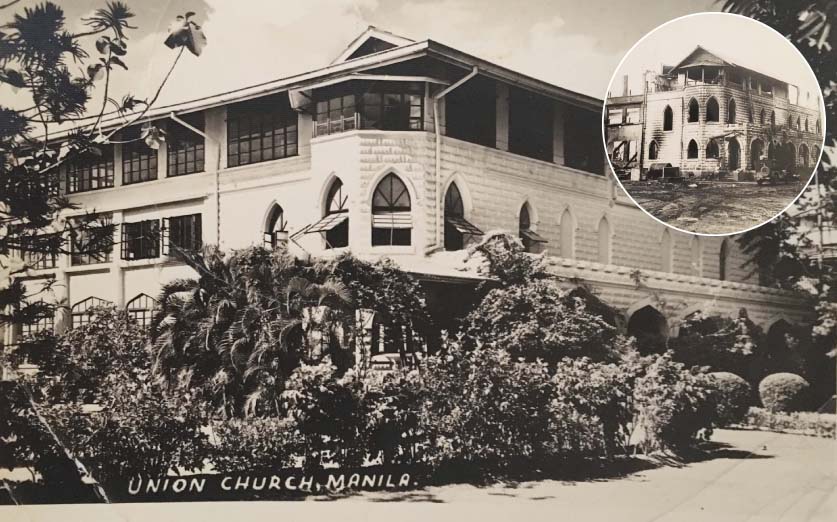

My mother, Frances Helen, was the storyteller. She and her parents, Walter Brooks Foley and Mary Rosengrant Foley, arrived in Manila in 1935. My grandfather served as pastor of the Union Church of Manila, then the leading non-denominational American Protestant church in the city.

It was a heady time for Americans. Manila was the Pearl of the Orient. A week after they arrived, the first Pan American Clipper sailed into Manila Bay with passengers and mail, crossing the Pacific in five days rather than the five weeks by boat, tying Manila and Asia more closely to the United States.

My family attended the inauguration of President Manuel L. Quezon in Malacañang Palace.

The Foleys lived in a lovely home at 222 Arquiza St., on the same block as the church at the corner of Padre Faura and A. Mabini streets. The house was full of international visitors and was the reception venue for church and community organizations. The living room could seat 35 without adding extra chairs. The Foleys quickly became key figures in the social and political networks of the time.

My grandfather, who trained not only as a theologian at the Boston School of Theology, but also as a sociologist at Boston University, was keenly aware of the wider patterns and movements of society.

From 1926-1931, the Foleys had been Methodist educational missionaries in India.

They learned Bengali and Hindustani, worked in rural villages and, after moving to Calcutta, became deeply involved with young Indian nationalists working for independence from the British. They left India for New York in 1931 under surveillance by the British secret police. I have a postcard from Mahatma Gandhi to Walter thanking my grandfather for his work.

During their travels in India, Burma, Malaysia, Hong Kong, China and Japan, my mother and grandparents experienced the events sweeping Asia: colonialism, nationalism, independence movements, calls for democracy, and incidences of violence and war.

After returning from India and serving churches in New York for four years, they arrived in the Philippines keenly aware of the aspirations of the Filipino people for independence, the history of American colonialism, and the rising tide of militarism in Asia, as Japan already began its occupation of China as early as 1931.

The Union Church served as the platform for expanding engagements with crucial matters of the time.

They became leaders in the resettlement of Jewish refugees from 1938-39. They also promoted healthcare work among the poor in Tondo and supported the Philippine independence efforts.

“Your grandparents were very close to the Chinese community,” my mother often said to me. “(Your grandfather) helped raise millions of dollars to support China’s resistance to Japan as president of the China Industrial Cooperatives,” she added.

She remembers going to large fundraising dinners at fancy Chinese restaurants.

My mother brought me to Manila in 1980 when I was still in high school. The stories began to come alive for me then when we visited the Manila Hotel by Manila Bay and the Union Church in its new location in Makati, walked the streets near their former home, and went to the church and halls of Santo Tomas where they were interned. We also visited my grandfather’s grave at the Masonic plot in Manila’s North Cemetery.

But when I enrolled in Columbia University in New York the next year, I thought I would go my own way, make my own path in life, and break away from all these stories.

In hindsight, I realize how deeply these family stories shaped my choices.

I graduated with a degree in East Asian Studies: Chinese Language and Culture. I learned Mandarin and spent eight months during my junior year studying in Beijing.

I then attended the Union Theological Seminary in New York. My first job was with the United Methodist Board of Global Ministries, the same organization that sent my grandparents to India 75 years earlier.

I earned a doctorate in cultural anthropology, not in sociology like my grandfather, and I became a professor, not a preacher, though I took on many leadership roles at my local United Methodist Church.

A few years ago, I began working with my mother to record and document her stories and write a book.

In the spring of 2017, I arrived in Manila ladened with many stories but in search of additional corroborations. I visited archives, worshipped at the Union Church, walked the streets of Ermita, visited my grandfather’s grave and walked the Santo Tomas campus again.

One day I visited Bahay Tsinoy, a museum located in the Intramuros premises of Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran, to seek the advice of Teresita Ang See. I shared my mother’s stories of my grandfather’s involvement in the Chinese community.

She graciously collected relevant books from the shelves of the museum’s library. One, written in Chinese, was the biography of Dee C. Chuan. Near the end of the book, in the chapter about Dee’s funeral, I found my grandfather’s name! He, along with Chinese Consul-General to the Philippines, C. Kuangson Young, and Philippine Vice President, Sergio Osmeña, had been eulogists at Dee’s funeral.

I knew then that I was on the right path.

When I returned to New York, I began to catalogue my mother’s extensive personal archive of papers and found more clues, including a piece of letterhead of the Philippine Association of Chinese Industrial Cooperatives.

My grandfather was listed as president. On the executive committee were Dee C. Chuan (李清泉), Yu Khe Thai (楊啓泰), Albino Sycip (薛敏佬) and Dalton Chen. Dee, Yu, Sycip and my grandfather were also members of the International Committee for Chinese Industrial Cooperatives in Hong Kong, chaired by Madame Sun Yat-sen, with Soong Tzu-wen, Edgar Snow and Rewi Alley as key leaders. Often called Indusco, the committee raised money to establish small industrial cooperatives in the interior of China for refugees displaced from coastal cities by the Japanese occupation. Its goal was to provide jobs and war relief and support the anti-Japanese war effort.

When the Japanese occupied Manila in early 1942, my family spent days destroying every piece of paper in the house that might incriminate others involved in the anti-Japanese efforts. All of Indusco’s records were destroyed, including treasured letters from Madame Sun and Madame Chiang. The Japanese military police, the Kempeitai, interrogated my grandfather seven times at his home about his activities and collaborators.

“We know you are connected to Chungking!” they shouted at him.

He never divulged his contacts, but the records of the organization were gone.

In the summer of 2019, I continued my search for these materials. I visited archives at Drew University, Boston University, Boston School of Theology, Union Theological Seminary, the New York Public Library, and the US National Archives in Washington, DC.

At Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library, I found gold. The New York office of the International Chinese Industrial Cooperatives group had left its archives there.

I found several folders of materials about my grandfather and the group’s efforts in the Philippines. One piece of letterhead listed a committee of 200 supporters, including many of the leading American, Chinese and Filipino civic and business leaders of the time. Their efforts were truly multiracial and interdenominational.

Considering the rising militarism of Japan, these people took significant risks by adding their names to the committee.

My mother often said that she and her parents would never have survived internment in Santo Tomas without their Chinese friends. Life in the prison camp was always uncertain, due to constant threats of violence, limited food supplies and the systematic undermining of every semblance of normal life.

In the last year and a half of the war when the Japanese were beginning to lose, they steadily reduced food supplies. Many internees died of starvation or diseases related to malnutrition. My mother weighed only 85 pounds upon liberation, while her mother had lost 50 pounds and her father, 25.

But in spite of their hardships, through the walls of the prison camp, their Chinese friends found ways, despite their own hardships in Manila, to smuggle food and money into the camp. My family has been forever grateful.

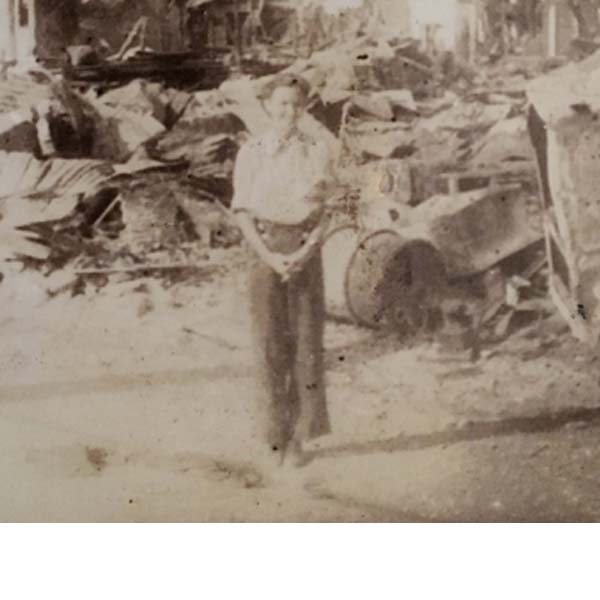

The tragedy for my family is that after surviving 37 months of internment in Santo Tomas, my grandfather was killed four days after liberation by a Japanese bomb, so he is buried in Manila. My grandmother was badly injured and lost her left arm. My mother was physically uninjured and nursed my grandmother back to health at the evacuation hospital of the Quezon Institute in Quezon City.

In a small notebook my mother kept after liberation are the names of their Chinese visitors – Albino Sycip, Yu Khe Thai and Dalton Chen. They invited my mother to their Manila homes for dinner and they helped locate my family’s possessions, which were hidden in five beautiful wooden trunks kept safe by Filipino neighbors. The chests were crated up in the lumberyard of Dee C. Chuan’s family and shipped back to New York.

As I am writing this, I am looking at three of them in my living room. My two sisters have one each of the others.

I returned again to Manila in September 2019. I brought with me a handwritten diary my mother had secretly kept during her time at the prison camp.

One afternoon I took a taxi to Santo Tomas and sat in the hallway of the main building where my family had lived those three years and read about their last harrowing months and final rescue on Feb. 3, 1945, exactly 75 years ago this month. Her entries were filled with descriptions of their hunger, their meager food supplies, their illnesses, and their confusion about the delayed arrival of American forces.

“Morale is deadly,” she wrote in her entry on Jan. 23. “The dealers [some Americans found ways of acquiring food and reselling at exorbitant prices] are trying to scare people into buying food and signing preposterous checks by telling how long troops will take to come.”

Two days later she continued, “The Chinese were our life savers. They gave out large loans to us and will not demand usury. The Crosby’s paid US$125 for 2 kilograms of white rice by check, so many people have forgotten the toadying with the enemy law. I hope the dealers are all court-martialed when this is over. So far, we have kept our skirts clean. People sign huge checks, trade diamonds, watches, rings, bracelets, pens, anything of material value, but there is no nutritional value in white rice.”

The day after reading those entries at Santo Tomas, with the help of Teresita Ang See, I was privileged to meet some of the grandchildren and kin of the Chinese friends who worked with and cared for my mother and grandparents.

What a thrill to meet them after all these years.

Over lunch and a long conversation, I was able to share my research about our families and the significant political and economic work they did together during that era. Perhaps most moving for me was the fact that I was able to thank them on behalf of my family for the kindness and friendship their families had shown to mine.

In so many ways the circle was complete, though I wonder if there is still more to come from this generation’s part of the story.