The Department of Education first proposed the no-homework policy in 2011. I wrote about it then, and I’m writing about it again now. This time though, I’m seeing this bill from Senator Grace Poe as a symptom of how our country’s officials view teachers and education.

In an ideal world, teachers are autonomous. They are the kings and queens of their own classrooms and do whatever they need to do to help students learn.

This can only happen if we trust the teachers. We can only trust the teachers if we know that they have been trained well, and their students are performing well in any kind of setting (not necessarily standardized tests, which I’m against, but that’s another story altogether).

More on teacher autonomy later. For now, let’s talk about homework. My stand has not changed from what I said eight years ago.

Teachers need to take a hard look at what they are assigning as homework. Is the homework helping students think deeply about questions that matter?

Prominent American educator and writer Alfie Kohn asks teachers: “What philosophy of teaching, what theory of learning, lies behind each assignment? Does it seem to assume that children are meaning makers – or empty vessels? Is learning regarded as a process that’s mostly active or passive? Is it about wrestling with ideas or mindlessly following directions?”

For the Philippine setting, I still view homework as mostly pointless. Things have changed at a snail’s pace. Much of the homework assigned to students in both private and public schools are still drills and textbook-based questions. There is barely any thinking involved; parents are not engaged with their children’s learning, except to follow what teacher requires.

Under the proposed bill, teachers may only assign homework to students on weekends provided that it be minimal and will not require more than four hours to be completed.

The bill cites a study from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Program for International Student Assessment (OECD-PISA) which indicates that additional time spent on homework has a negligible impact on the performance of students. This is after around four hours of homework in a week. Further, it looked at homework hours around the world and found that there wasn’t much of a connection between how much homework students of a particular country have and how well their students score on tests.

That citation is extremely misleading. It cites PISA findings from 2015. The Philippines has never been a participant in PISA, until the 2018 study whose results are yet to come out this December. Even then, I am not sure if the 2018 results will include data from the Philippines because:

(1) We are not a member of OECD

(2) Previous results only included countries that have been PISA participants for two consecutive studies.

Also, the reference to the homework citation has been paraphrased to fit what Senator Poe wants to reflect. The actual statement refers only to Science and not the entire spectrum of subjects. Worse, the PISA statement is not even about homework itself!

To quote the PISA results, “School systems where students spend more time learning after school, by doing homework, receiving additional instruction or in private study, tend to perform less well in science.”

The worst thing about the bill is that it is set to penalize teachers who assign homework. This shows how little trust we have in our teachers. If we don’t trust our teachers to do the right thing, and we have to treat them like errant children, why bother having teachers at all?

There are processes instituted by the Department of Education to empower teachers and have them improve their quality of teaching. The National Competency-Based Standards for Teachers was a great start in 2007. It has been improved and changed to the Philippine Professionalization Standards for Teachers in 2017. Under the PPST, teachers have to meet qualitative standards as part of their performance evaluations.

If all teachers pull up their bootstraps and strive to get excellent ratings in all seven domains of the PPST, the homework question will become moot. Teachers will naturally end up assigning meaningful homework.

What does meaningful homework look like? Meaningful homework should get students to think of their own work, use the skills they learned in school and, hopefully, engage parents in their child’s education.

Let me cite my children’s homework from a progressive school.

One of Shobe’s homework is to practice measuring (Maths and cooking), use PowerPoint features like animation and transitions (Technology), as well as public speaking (Filipino). Her homework? They were asked to cook something, have their pictures taken while cooking, put the photos on PowerPoint, and have an audio recording explaining their processes. Parents are engaged because I took the photos and audio recording, tasted and praised her cooking, sat beside her when she did her PowerPoint presentation. She even asked what slide backgrounds I liked.

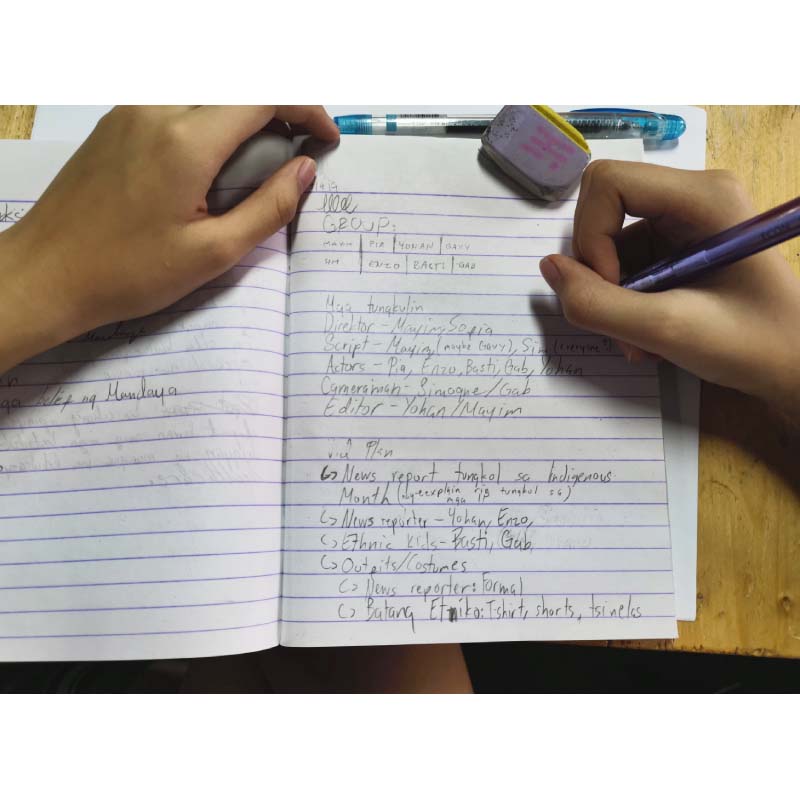

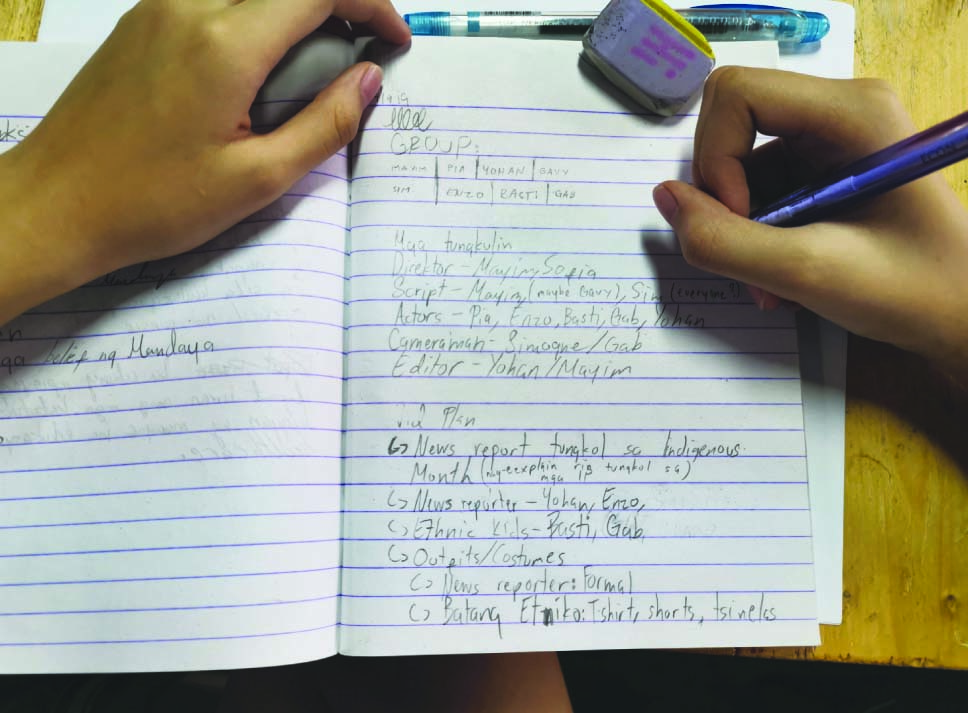

Meanwhile, Achi’s homework in Grade 7 is more complex involving myriad skills and content knowledge. Also, Achi has never liked anyone hovering while she worked. It has been like that since third grade, so I have rarely supervised her or butted in on her work, unless asked. One of the homework instructions I saw was for the class to research something for Araling Panlipunan (Social Studies), and students could choose which output to submit: an infograph, an essay or a video recording of the student making a speech.

For both girls, homework has a lead time of five days minimum. There is often a weekend available for completion.

As Kohn indicated, children are involved in active learning as they make meaning out of this work. They are not automatons repeating drills from school.

In education parlance, there is transfer of learning – where children learn particular content and skills, and use them innovatively in other areas. This is what meaningful homework is.

This comes from having qualified teachers, not legislation.