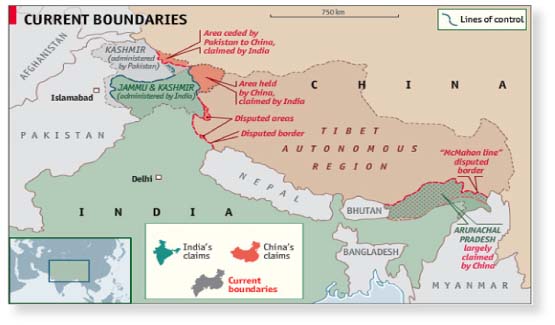

It is not just in the South China Sea region that China comes into conflict with other countries when it comes to border disputes and territorial claims. India has its own contentious issues with China.

The Doklam plateau, an area claimed by both Bhutan and China, is one such area.

There are many reasons behind the persistence of present conflicts and tensions between India and China, which began with the delineation of borders in the Himalayas at the end of the colonial period.

The economic and diplomatic relations, as well as the numerous cooperations, they have reinforced or engaged in different countries, have given rise to new forms of latent conflicts. The growing presence of China in the Indian Ocean, and its strengthened ties with Pakistan, have heightened tensions.

The road construction initiatives by the Chinese in Bhutan have raised other issues: the possible control of China over the Brahmaputra waters and a division of India’s territory.

The Doklam plateau is a strategic region for India. It forms a vantage point of entry from where to launch an attack on the Siliguri Corridor. This 24 km-wide strip of land is also called “the chicken’s neck” and links the major part of India to its northeastern states.

If China gains control of it, India would be split into two, and China could control the upstream section of the Brahmaputra River and therefore command the supply of freshwater, as well as giving China easy access to transportation of war machinery such as tanks and vehicles to the border of India.

Upon the request of Bhutan, an ally of India, Indian soldiers occupied the Doklam plateau to prevent Beijing from constructing a road extension southward towards Doklam. The road was built by China in 2005, and a southward expansion would reach the Indian border.

On June 18, 2017, around 270 Indian troops, with weapons and two bulldozers, entered Doklam to stop Chinese troops from constructing the road extension. China’s response was to send troops from the People’s Liberation Army.

Fortunately, both sides agreed to resort to diplomacy to resolve the issue and actual skirmishes were averted in the Doklam standoff. On Aug. 28, 2017, two days before the BRICS conference held in China, both India and China announced that they had withdrawn all their troops from the tension-filled border standoff in Doklam.

India-China Himalayan border

The Himalayan mountain range forms a natural border between India and China. However, this mountainous space is occupied by numerous economically and politically weak small states.

By forging alliances with them, India and China hope to protect their respective interests. These small states are also compelled to open up to either of the two giants for their own economic development and to foster the movement of populations.

Thus, building roads towards India would allow the Nepalese to go to India, while building roads towards China would allow access to a supply of cheap manufactured goods towards India’s neighboring states.

Unfortunately, such road constructions in Nepal and in Bhutan are seen as not just enabling mobility of people and goods, but as a strategic entry point for possible conquest by China as well.

The situation feeds a string of tensions between the two countries arising from other geopolitical developments in the area. India is worried about the strengthening of military and economic cooperation between China and its neighbors, namely Pakistan and Sri Lanka; with whom China has already sealed military and economic agreements related to the “String of Pearls” network throughout the Indian Ocean.

The port of Hambantota in Sri Lanka and the port of Gwadar in Pakistan will be accommodating Chinese warships.

Sino-Indian relations have not always been so fraught. The diplomatic relations between India and China were relatively courteous during the 1950s; they were even good in 1950 when Indian Prime Minister Nehru supported China in its quest for admission to the United Nations.

When Beijing annexed Tibet in 1950-1951, India did nothing; although India welcomed the Tibetan government in exile as well as many Tibetan refugees.

In 1956, the Chinese made a road going from Xinjiang to Tibet, crossing the Aksai Chin, another common border between China and India, and posted troops there without the Indians being aware of it as there was not much Indian presence there.

The Dalai Lama’s escape to India in 1959 convinced China to push further. Zhou Enlai offered to give up the Arunachal Pradesh if India dropped its claims over the Aksai Chin. In response, India set up border posts in the Aksai Chin and incidents with Chinese soldiers increased.

Since then, the Chinese threat in the Himalayas, which overlooks the Ganges Valley and the Indian political and economic backbone, is almost constant. Armed conflict broke out in 1962 due to these territorial disputes. Though the war did not last long, it had a lasting impact in fostering mutual suspicion and distrust.

China’s border expansions

In the 15 years since the 1962 border conflict, China has strengthened its naval force, intending to have coastal bases to anchor their battleships, which has shifted the tensions with India to southern coastlines and borders.

These tensions have become complex, with China creating diplomatic ties in all directions for its projects along the “New Silk Road” or the “String of Pearls” in the Indian Ocean.

The rapprochement between China and Pakistan, India’s worse enemy, dates back to the 1962 conflict as well. Beijing and Pakistan reached an agreement that set the borders shared by their two countries, and India found itself surrounded by hostile neighboring countries.

Relations with China warmed up in the 1980s, particularly with Rajiv Gandhi’s visit to Beijing in 1988. Both counties aimed at pacifying the border relations and reinforcing economic cooperation, and the issue of the borders seemed to be set aside. India recognized in 2003 that Tibet “is a part of the People’s Republic of China territory.”

In latter years, tensions and incidents between India and China have again been increasing. China has been developing its “String of Pearls” in the Indian Ocean through military agreements with Sri Lanka, with Pakistan, and by setting up radars in Myanmar that are capable of keeping watch over the Andaman and Nicobar Islands both belonging to India.

The fear of being surrounded bears on the diplomatic relations of India with its neighbors. Pakistan’s partnering with China since 1962 has been the subject of great concern.

China has given Pakistan the technology that allows it to access the nuclear weapon, and to carry on the latent conflict it has with India. Pakistan has become a major development route for China with the creation of an economic corridor that crosses through Pakistan allowing access to the Indian Ocean.

This corridor is supposed to link the Chinese province of Xinjiang to the Indian Ocean, passing through the Pakistani provinces of Punjab and Sind, and also the part of Kashmir occupied by Pakistan. A series of infrastructures are in the pipeline: road, railway, structures for energy production and special economic zones.

India’s economic thrusts

Competition between the two emerging countries is also economic: India launched its “Made in India” to compete with China in the market of manufactured goods. In the 1990s, India began several diplomatic and economic initiatives towards Eastern Asia within the “Look East Policy” framework.

India began establishing ties with Japan, South Korea and Australia in 2003. India’s center of gravity has shifted to the Pacific Ocean, China’s backyard, in the context of China’s hegemony and constructions in the South China Sea being contested by bordering countries (with the Philippines at the lead, at least up to 2016).

In 2008, the American Congress signed an agreement with India on nuclear energy: selling technologies and nuclear fuel for civilian use were made possible even while India had not signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. This strengthening of diplomatic relations serves the United States’ interest to bar China’s expansionist intentions.

At the same time, India also moved closer to Israel with the long-term view of fighting Islamist terrorism.

India and China are rivals but as demonstrated in many countries, economics is paramount and is an area where they can cooperate, despite their differences. The BRICS framework (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) of cooperation has been quite productive.

Beijing has wanted Delhi to become member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and Delhi, in turn, has accepted Beijing as an observer in the South Asia Association for Regional Cooperation.

The two States share a common opinion regarding globalization and the much too prominent place of the United States in international relations. These two nations, together with Russia and the USA, are part of the new world order.

Urban policy is at the heart of the diplomatic game between India and China. The projects transforming the Chinese district in Tangra, Kolkata, are an example that show the different layers of influence involved in this complex diplomatic game. With the aim of turning the district into a tourist destination, Chinese arches as decorative feature has been imported from China.

The City authorities, holders of building and business permits, of water and electricity conveyance, seem to be dictating the transformation of the Chinese districts in Kolkata into touristic areas. The power plays go well beyond the local Chinese community who has very little influence and cannot oppose the decisions made by the city authorities.

The latter see such projects as a broadening of relations between China and the Indian Union, or more specifically, between the cities of Kunming and Kolkata.

University exchange programs are in progress between several universities of West Bengal and those of Yunnan. In transportation, some cooperation is also being initiated to connect Kolkata to Yunnan with the construction of a transport corridor going through Bangladesh and Myanmar.

The province of Yunnan is a focal point in Chinese projects aimed at India since the beginning of the 1990s, and this rapprochement is part of India’s “Look East Policy.” This policy is a set of initiatives promoting trans-regional cooperation such as the “Kunming initiative” launched in 1999 and bringing together Bangladesh, China, India and Myanmar.

The objective of this initiative is to open up to nearby regions by creating economic synergies. China advances its interests in India in this way, through the twinning of cities, just like with other cities.

In Manila, the building of Chinese arches is proof of this phenomenon which exceeds the diplomatic relations between countries.

The Chinese presence around India takes on various forms and at various sites, starting off a new phase in diplomatic relations between the two countries. Thankfully, lessons from past disputes and how conflicts were resolved through diplomacy instead of outright violence have been instilled on both sides.

Economic needs and the positive outcome of economic cooperation seem to provide incentive for setting aside differences for mutual benefit and faster development.