Place names are integral to the rich heritage and history of the locale. Often, these names tell of stories, origins and legends there.

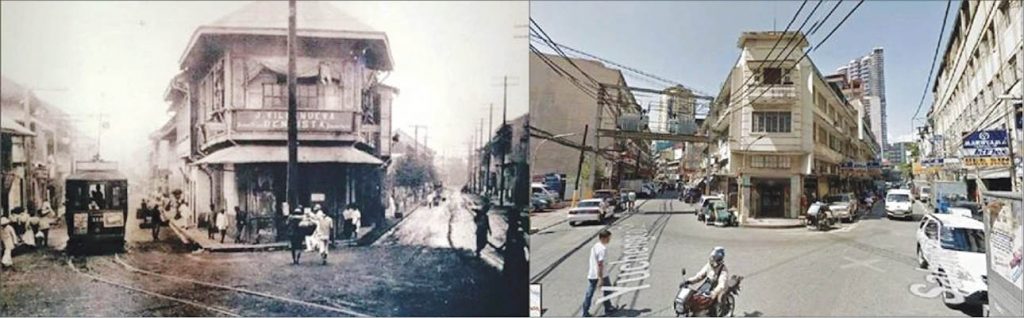

Recently, controversy arising from the proposed building of the Philippine-China Friendship Bridge spanning Intramuros to Binondo sparked renewed interest in the adverse impact of the destruction of historic places especially in Binondo.

Groups such as The International Council on Monuments and Sites, Chamber of Commerce of the Philippine Islands and Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran, Inc. point out that a pedestrian bridge rather than a four-lane bridge open to motorists is more appropriate.

On the Binondo side, traffic cannot be eased because its streets are narrow, the groups say. Traffic will worsen with the bridge because it ends in the worst chokepoints.

Second, it will potentially worsen the flooding of Binondo because bridge pilings will be at the Estero de Binondo. This will hamper the flow of water and further constrict the already narrowed Estero.

Third, and most important of all, is the destruction of an important part of Manila’s history and heritage, especially San Fernando Bridge, one of the historic structures that will be completely torn down.

Not many young people remember that the early Chinese immigrants knew San Fernando Bridge only by its old name Baybay Bridge (baybay kio in Hokkien). It was in the “town” called Baybay town, now known to us as San Nicolas district.

The bridge was built in 1796. The maestro de obra was Policarpio Fajarado and the foreman was Phelipe Sta. Mesa. It was constructed as a flat deck bridge supported by a single masonry pier. The stone materials for the bridge came mainly from Meycauayan, Bulacan. When the bridge first opened, it was widely regarded as an major engineering feat.

Baybay Bridge

Baybay is the Tagalog word for shore because the town was fringed by the Pasig River and its tributaries or esteros.

Baybay Bridge is significant to the Chinese because it was where the early immigrants – our ancestors – came on shore after quarantine on Engineer Island. On the spot where they came ashore now stands the BDO building and the fire station cum charity clinic opposite.

Engineer Island (now called Baseco) was called tsui tsu (水厝 or water house) by immigrants, depicting how they were immediately hosed down with water and deloused with disinfectant after a grueling journey aboard ships.

They docked at Engineer Island where they were examined and quarantined for weeks to make sure they did not have contagious diseases. They were then brought by bancas to Baybay Bridge where they went ashore and reported to the Chinese consulate and the Comunidad de Chino at the other end of San Fernando Street.

Yes, the first consulate and the first Comunidad de Chino were located at San Fernando. The two groups established the Anglo Chinese School, the first Chinese school, in 1899 at the site of the first consulate.

The old Te Yah Kong Temple (帝爺公廟) beside Baybay Bridge was in olden days just a small shrine for Guan Te Yah (關帝爺/關羽 Taoist God of War). The image was supposed to be brought by early immigrants for protection and they built a shrine as gratitude for a safe journey.

Another tale is that Spanish soldiers attempted to repel some immigrants coming ashore at Baybay Bridge, but they saw an apparition of a Chinese warrior and retreated. The Chinese immigrants said the apparition was of Te Yah Kong. The Te Yah Kong Temple is still found on Ongpin Street.

More historic sites

There are many other historic sites in Binondo and San Nicolas that may be affected by the roads leading to and away from the proposed Friendship Bridge.

For instance, some historians attest that the site of the old State Investment House, now the State Center, could have been the location of the fictitious white house of Capitan Tiago in Jose Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere. The novel’s first chapter opens with “a dinner party one evening toward the end of October in the 1880s in a house on Anloague,” now called Juan Luna Street, where the State Center is located.

This is proof of the great place Binondo always had in Philippine history. It was in Binondo where Rizal’s family lived after the hero’s death. On a tiny street off Juan Luna called Estraude Street was where Rizal’s father died. On Calle San Fernando stood the house where his siblings lived, and where his mother died.

Antonio Luna was born on Urbiztondo Street, just off the busy Muelle de Binondo where cascoes and boats traversed, bringing goods and merchandise all over Luzon.

Our first Filipino saint, San Lorenzo Ruiz, was born in Binondo and was a sacristan in Binondo Church. The La Liga Filipina was founded in the house of Doroteo Ongjunco on Ylaya Street. Ang Kalayaan, organ of the Katipunan edited by Emilio Jacinto, was published on Lavezares Street – all in Binondo.

“Binondo’s heyday went beyond Manila-Acapulco trade (1593-1815) – Manila was the hub of east and west, its galleons ferried Chinese silks, Persian rugs, ivory and musk, ilang-ilang essence, spices and other oriental rarities to the Spanish Americans – then to Europe – and vast caches of Mexican silver which flowed as much-coveted currency over the whole of Southeast and Central Asia,” said historians Luning Ira and Isagani Medina in their well-researched book The Streets of Manila.

Ilang-Ilang Street still exists. It was so named because ilang-ilang essence, distilled in the area with improvised extractors, was once an important export to Europe and Great Britain. We learned from the late historian Pio Andrade that our Manila ilang-ilang essence was patented by designer Yves Saint Laurent in France so we stopped selling it.

Binondo’s streets, extending to the San Nicolas district, are witnesses to the historicity of the place. This history may soon be erased at the rate public officials keep changing the street names. We have lost Rosario Street to Quintin Paredes because of ignorance.

Rosario was named after Our Lady of Rosary (Nuestra Señora del Rosario), the district’s patron saint. It was one of the main streets of early Binondo – by no stretch of imagination can a senator (Quintin Paredes), though an outstanding public servant, be more important than a whole district’s patron saint.

Nor is Sabino Padilla more significant than Gandara (Jose de la Gandara), the “Spanish governor general who, during his term, established a telegraph system, built lighthouses and created the first Department of Mines of the Philippines,” according to the Facebook page of the Philippine History and Architecture.

Sabino Padilla’s family owned a lot of the real estate in Binondo. Whoever heard of naming a street after the landlord? Yet his named trumped Gandara’s.

Religious sites

Rosario goes well with Magdalena, Sto. Cristo, San Fernando, Reina Regente, Veronica, San Nicolas, Sta. Elena (to emphasize the religiosity of a Binondo controlled by Dominican friars) but not with a Quintin Paredes and a Masangkay, the new name of Magdalena Street.

Other streets that depict Binondo’s religious preoccupation include Moraga and Alvarado, both Augustinian priests, saints like San Vicente, San Gabriel, San Nicolas and San Fernando (Spain’s Ferdinand III, canonized after he threw out the Moors, and introduced the Inquisition).

We should not forget Salazar Street named after Domingo de Salazar, Manila’s first archbishop, who sent voluminous reports to the Spanish king lauding the commerce brought in by the Chinese and the skills of the artisans which served to make life easier and more comfortable for the Spanish colonizers.

The street crossing Salazar is Benavidez, one of the many Spanish priests who learned Chinese to convert the Chinese in Binondo to Christianity, in line with Spain’s ambition to proselytize all of China eventually.

Another little-known street is Valderrama, named after Fr. Pedro de Valderrama who celebrated the first mass in the Philippines in Limasawa (reported to be Masao in Butuan).

Another, Sta. Elena, is traditionally known as the street selling Chinese delicacies sourced from all over the Philippines like fresh abalone, jelly fish, seaweeds, sea cucumber and all kinds of dried fish. It is named after the mother of Roman emperor Constantine the Great, who embraced Christianity.

The Filipino’s favorite pastime in the month of May – the Santacruzan – was actually Queen Elena and Prince Constantine’s search for the true cross of Christ.

A stone’s throw away from Sta. Elena is Sto. Cristo, the Holy Christ, which used to house the first women’s school, the Instituto de Mujeres.

Aside from Magdalena, now renamed Masangkay, other Marian-based street names are Veronica, the woman in Jerusalem who followed Christ to Calvary, and Asuncion, named after the Assumption of the Virgin Mary.

Binondo as a commercial hub and base for Chinese artisans is reflected in street names based on noted Chinese occupations during Spanish time.

The most well-known is, of course, Anloague, meaning carpenter. Renamed Juan Luna in 1913, it is the other main street in Binondo next to Rosario and is now a respectable business address – Chinatown’s “Wall Street” – where prestigious banks, investment houses and insurance firms are located within view of the Pasig River.

Other occupations include Jaboneros (soap makers), Fundidor (foundry workers), Fumadores (smoking stations), Alcaiceria (silk market) and Comercio.

Spanish governors

Streets named after famous Spanish figures include Cervantes, the favorite Spanish novelist who wrote the novel Don Quixote de la Mancha.

Callejon Carvajal is named after the Supreme Court justice who, in 1784, helped Governor-General Jose Basco set up the tobacco monopoly. Carvajal is known by the Chinese (until now) as ho-sua hang (alley of umbrellas) since it used to house umbrella makers.

Dasmariñas is named after the infamous Gov. Perez de Dasmariñas whose death actually triggered the first big wholesale massacre of the Chinese in 1603. Despite this odious background, retaining its name is a historical reminder of the bitter struggle of our early immigrant ancestors to find “their place under the Philippine sun,” a struggle which at times entombed all their dreams.

Governor Damariñas attempted to send an expedition to conquer Indonesia’s Moluccas in 1593 but was killed after the conscripted or kidnapped Chinese rowers mutinied when they learned the purpose of the expedition.

The rowers suspected they would either die at sea due to the atrocious conditions in the small, poorly ventilated, jam-packed galley or die in Moluccas when the military expedition failed. They chose to try their luck by killing the captain.

The governor’s son, Luis Perez de Dasmariñas, succeeded him as governor, and his bitterness over his father’s death led to additional repression and persecution of the Chinese. He got his revenge when over 23,000 Chinese were massacred in 1603, leaving only 200 alive.

Two other governors, Guido de Lavezares and Francisco de Sande (which are also street names), were partly responsible for the series of events that led to the massacre. It happened 18 years (1575) before Dasmariñas’s death but served to feed the Spanish fear and mistrust of the Chinese.

Historical accounts showed that Sande, who succeeded Lavezares, received three Chinese envoys who bore gifts for Lavezares. The envoys refused to hand over the gifts to the incumbent governor without authority from their superiors in China.

Sande was insulted and offended. This Chinese faux pas led to a bitter anti-Chinese policy in Sande’s administration which continued to Dasmariñas’ time.

In contrast to the infamous Dasmariñas was Narciso Claveria y Zaldua (for which Claveria Street is named), believed to be one of the best governors the Philippines had (1844-1849). He organized the municipalities, dashed French attempts to conquer Basilan in Sulu and issued the catalogo alfabetico, the alphabetical list of Spanish names which became the basis of most Spanish surnames Filipinos adopted.

Other streets named after Spanish governors include Peñaranda, Lara, Urbistondo, Tabora, Camba, Folgueras. Governor Sabiniano Manrique de Lara did not find Malacañang grand enough for him; he merged the colleges of Sta. Isabel and Sta. Potenciana in 1866 to be his quarters, an extravagance which cost him his job that same year. Loaisa Street is named after Garcia Joffre Loaisa, a Spanish explorer who headed expeditions to the Orient. Elcano Street is named after Sebastian del Cano, the first person to circumnavigate the world.

Spanish cities

The ties with Spain are reflected in such names as Reina Regente, Maria Cristina of Spain, mother of Alfonso XII and queen regent from 1885 to 1902; Felipe II, Madrid, Sevilla, Barcelona (Spain’s major cities) and Numancia (a Spanish town).

Not all street names reflect a serious preoccupation with religion or history. The name Binondo itself could have come from binundoc or hilly/mountainous area. Could Manila in pre-Hispanic times have been a mountainous area like Cavite that was later engulfed by the sea that formed Manila Bay?

Our heritage

Other more whimsical names are Meisic, from the Tagalog may intsik or ma-intsik, and Hormiga, a small side street linking the main streets Rosario and Juan Luna. Hormiga means ants, apparently referring to the ant-paced traffic on Rosario and Juan Luna back during the days of horse-drawn carriages.

Yes, traffic was bad even back then!

Clavel is a Spanish flower and Caballeros is a riding track of Spanish horsemen. Although there is a Mestizo Street, it is Caballeros Street that is known by the Chinese as chut-si-ah-hang, the alley of mestizos. Not far from Caballeros is a small street called Mestizo, attesting to the intermarriage then.

Who would have thought our rich heritage is embodied in simple street names? These speak volumes of events in the Philippines’ historic past.

So, before our public officials and their partners think of destroying a part of Binondo, they should remember that they are erasing a rich historical heritage that makes it – and Manila – unique.

Meycauayan, Marikina and Maypajo are names that reflect their immediate surroundings, just as Maynila was named after the nilad flowers in the Pasig River. Even world-famous names like Cambridge and Oxford reflect precisely the English countryside where its four-legged denizens – lamb and oxen – used to cross.

Heritage – whether bucolic or eventful – makes people who they are today. To destroy that heritage is to inflict a tragic blow our identity.