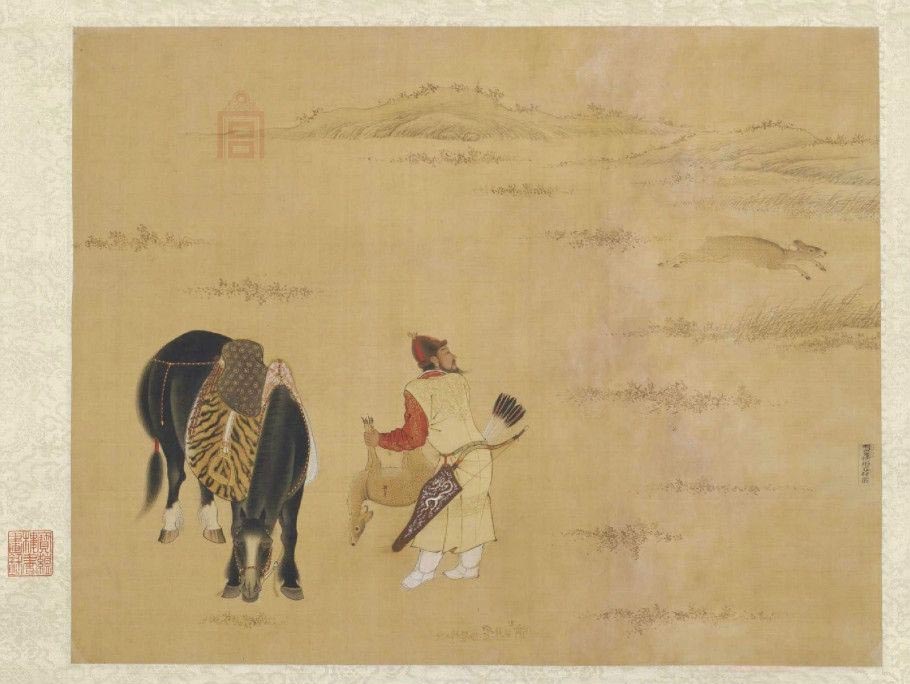

In April 1434, Ming Emperor Zhu Zhan Ji (朱瞻基, 1426-1436) accompanied the Empress Dowager to the Chang Mausoleum (長陵) and Xian Mausoleum (獻陵) to pay homage. On their way home, when they reached the suburb of Chang Ping (昌平), Zhu saw common people along the roadside tilling the fields. He got off the horse and made inquiries. He even tried to work the plow himself.

In April 1434, Ming Emperor Zhu Zhan Ji (朱瞻基, 1426-1436) accompanied the Empress Dowager to the Chang Mausoleum (長陵) and Xian Mausoleum (獻陵) to pay homage. On their way home, when they reached the suburb of Chang Ping (昌平), Zhu saw common people along the roadside tilling the fields. He got off the horse and made inquiries. He even tried to work the plow himself.

After a while, Zhu said, “I just tried to plow two to three times, yet I felt tired already. I cannot imagine the common people who till the fields throughout the year. People always say farming is the hardest occupation, it really is.”

Upon returning to the palace, Zhu wrote, “During the spring, as I returned from paying homage at two mausoleums, I saw farmers tilling the fields with their heads bowed. I called them over and asked: ‘Why work so hard tilling the farm?’ A farmer knelt down and replied, ‘Diligence in tilling the farm is our duty.’

“I asked, ‘Do you have time to rest?’ The answer: ‘In farming, we farmers till in spring, plant in summer and harvest in autumn. In all these three seasons, we have to work on time. Once we miss the season, we will have no harvest in autumn and would suffer from hunger.’

“I asked, ‘So you rest during winter?’ They answered, ‘We can’t rest even during winter. We have to render corvee to the municipal government. We dare not go.”

“I asked, ‘You farmers work so hard during four seasons. Why not look for other occupations, such as study and become government officials, or artisans, or merchants, so you would have time to rest?’ Their answer: ‘My ancestors for generations were all farmers, it is difficult for me to change. This village has no scholars, no artisans, so I don’t know if they have time to rest.

‘With regards to merchants, they also have a hard time. They peddle on the street and alleys, traveling as far as 200 to 300 li (里, one li is half a kilometer) to sell their wares. Sometimes, they would be gone for as long as one month, or at least 10 days, before they could return home, with profit of at most 20 to 30 percent, or only 10 percent. There were cases when they lost all, including their capital. In dire situations, the whole family suffers without food and clothing.

‘For those who till farms like us, if there is no natural calamity or plague of insects, as long as we work hard and the harvest is good, it would provide us food and clothes to last us two years. If we harvest less, it could still be good enough for a year’s provisions. More so, the whole family is always together and happy. Thus, we would rather be in farming than be in another occupation.’

“I asked, ‘Based on your observation, what else do you know aside from the hardships of merchants?”

Their answer: ‘We are villagers, we know very little. I went several times to the municipality to render corvee and met two head officials. One would leave home early in the morning and return late in the evening. He tried his best to handle civil matters, unremittingly, for fear that if he did not exert his best effort, the common people might suffer. When he got promoted and left, the common people still miss him until now. The other one only sat in his office every day. He did not care for the weal and woe of the common people. He was dismissed. When he came to Chang Ping sometimes, people ignored him.’

Zhu Zhan Ji concluded his inquiry, sighed with emotion, and pondered deeply over what the farmer had said – it was simple, plain but contained profound truth.

Categories

Emperor learns from farmer