Washington SyCip’s lifetime achievements span several generations on all continents. Global and national leaders, public figures and business tycoons sought his ideas, opinions and analyses on significant political, social and economic issues. Many outstanding leaders in the Philippines and Asia were honed by SyCip Gorres Velayo & Co. or the Asian Institute of Management, both of which he founded.

SyCip had directorships in a wide range of giant corporations and advisory councils in Asia, Australia, Europe and the United States. In accepting these positions, he made sure to attend the meetings as often as his schedule permitted. He would show up at those international meetings in a natty suit and tie (he keeps suits of clothes in several capitals), ready to dispense radical advice and ideas, when they are sought.

National leaders, politicians, public figures and business tycoons who wanted to pick his brain on political, social and economic issues do not go away disappointed. They always learn something of value from “The Wise Old Owl.”

He was not afraid to speak his mind: people knew that when they invite him as a guest speaker and/or if his opinions were sought, he would speak his mind and say things that his host may not want to hear – a mark of the man’s integrity.

Despite being recognized as a citizen of the world, SyCip’s heart nevertheless lay on Philippine soil. His greatest anxiety was seeing the Philippines forever mired in where it is today – from a leading Asian nation in the 1960s, to barely ahead of Burma, Laos and Cambodia today. His greatest passion was to see the Philippines grow and develop, its citizens educated and productive.

SyCip’s family was typical of overseas Chinese families of the early 20th century. SyCip’s grandfather migrated to the Philippines sometime in the mid-19th century to escape the turmoil China was undergoing during that period.

His grandfather, Sy Ching Cip, was from Xiamen, Fujian province, China. Two of his sons, Alfonso and Albino, became renowned leaders in the Chinese community and founders of important community institutions, among which were the Chinese Chamber of Commerce (founded in 1904), Chinese Charitable Association and the Anglo-Chinese School (the first Chinese school established in the Philippines in 1899).

Born in 1883 in Manila, Alfonso was educated in China and returned to the Philippines in 1903. He worked in Cebu for 11 years and founded the Cebu Chinese Chamber of Commerce, Cebu Chinese School, Chong Hua Hospital and the Chinese cemetery in Cebu. He came to Manila in 1912 and became one of the leaders of the Manila Chinese community. His longest stint in a Chinese organization was as president of the Manila Chinese Chamber of Commerce.

Albino, Washington’s father, was born in 1887. After his education in China, he pursued studies in Law at the Michigan University in the United States. Upon receiving his law degree, he returned to the Philippines in 1912 and topped the Philippine Bar examination that year (the president of the University of the Philippines, Jorge Bocobo, placed second).

His wife, Helen Bau, came from a prosperous Chinese Presbyterian family in Shanghai, which owned the Chinese Commercial Press, the largest printing press in Asia at the time. Meeting on their way back to Asia from studies in the United States, Albino and Helen settled in the Philippines.

Albino was one of the founding trustees of China Banking Corporation, the first Chinese-owned commercial bank in the Philippines founded in 1924.

The Philippines was a US colony from 1898 to 1946. In February 1921, Alfonso, as vice president of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce (with Dee C. Chuan as president), presented to Governor-General Francis B. Harrison a petition against the Bookkeeping Law, which banned Chinese businessmen from keeping their books of accounts in Chinese. The Chamber lost the case in the Philippines. Dee and Alfonso sent Albino, the lawyer (accompanied by another officer, Rafael Gotauco), to represent the Chinese community to argue the case against the Bookkeeping Law before the United States Supreme Court. The case was won, and the law was declared unconstitutional.

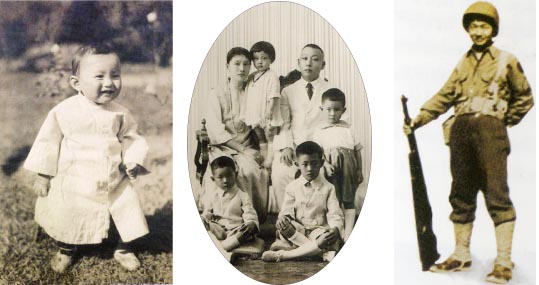

Both Alfonso and Albino were key leaders in the anti-Japanese resistance movements, for which they were imprisoned in January 1942. Alfonso was granted amnesty after one year because of his age and released on Feb. 18, 1943. Alfonso’s family fled to Fuga Island in Aparri, Northern Luzon to avoid being under Japanese rule. Unfortunately, some of them died when the US bombed Fuga.

Albino’s family decided to stay behind in Manila so that they could visit him in prison. This decision saved them from harm.

Washington SyCip was born on June 30, 1921 while his father Albino was fighting against the Bookkeeping Law in the US Supreme Court in Washington. Elated over his victory, Albino chose to name his infant after the capital of the United States. Two older sons, David (born 1917) and Alexander (born 1919), were also named after leaders.

Bowing to the wishes of his maternal grandmother, SyCip’s parents took him to Shanghai to live for five years. He learned to speak Shanghainese and was taught Chinese by private tutors. He came home to Manila every once in a while, but his mother visited him frequently. As the time for his formal schooling approached, she brought him back to the Philippines.

SyCip’s father insisted that he and his siblings study in Filipino public schools and that they walk to school three kilometers away, instead of riding in the family car. Albino did not want his children to grow up only in the company of the rich, or associate only with a specific racial or cultural group.

Compared to his two brothers, Washington had a more difficult time back in the Philippines because he would be teased for his Chinese ways and accent. It is a tribute to the man’s genius that he learned to speak perfect English and graduated at the top of his class both at P. Burgos Elementary School and later at V. Mapa High School.

SyCip was one of the most respected names in the world. “Perhaps my Chinese heritage contributed a lot to whatever success I may have achieved,” Washington once said. “My father had always taught me that it’s really important to work hard and be frugal.” He would later also adopt his father’s policy not to allow his children to work in his company.

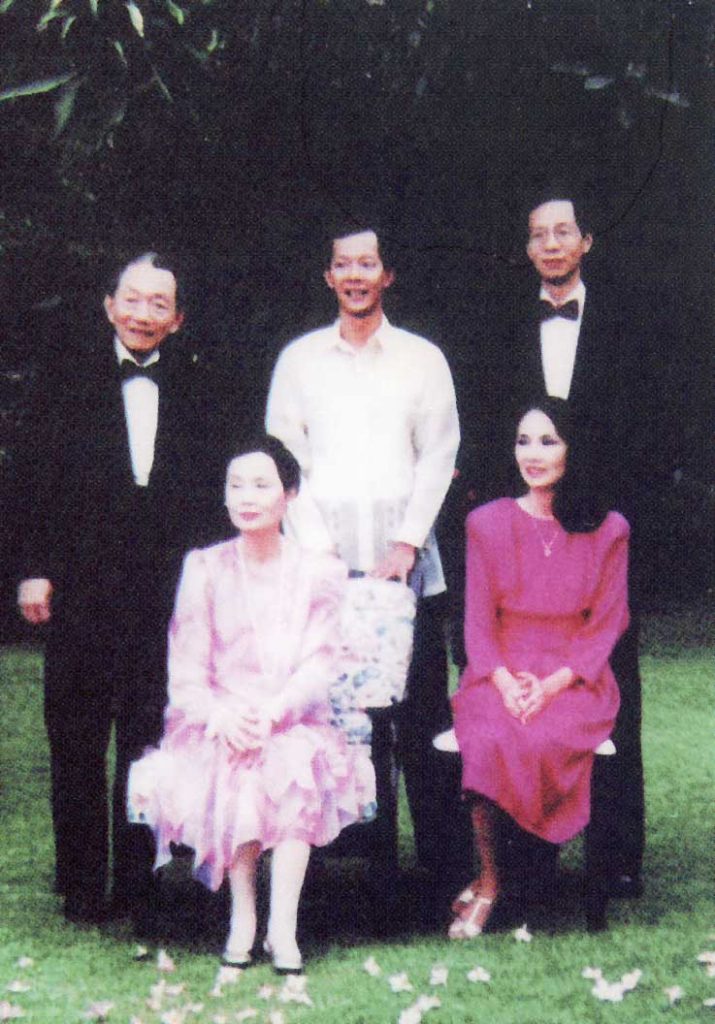

Albino’s policy worked. His three sons’ successes were all hailed as their own personal accomplishments. Wash’s brothers – David, a successful businessman, and Alexander, a lawyer – were also renowned in their time. David headed the Asset Privatization Trust in the post-Ferdinand Marcos regime, handling the privatization and returning to their rightful owners of the many assets sequestered by Marcos. Alexander’s law office was good training ground for young interns like law graduate Franklin Drilon, who would become president of the Senate of the Philippines. Two sisters, Elizabeth and Paz, were born after the boys.

Washington married Anna, daughter of Yu Khe Thai, the most prominent Chinese-Filipino businessman during the post-war period. His brother David married Anna’s sister Helen. They were all childhood friends.

Washington SyCip himself had three children – sons George, a businessman and an investment counselor, and Robert, an investor, and daughter Vicky, an educator.

SyCip graduated summa cum laude in accounting from the University of Sto. Tomas in Manila. He passed the board exam for Certified Public Accountants at age 19, two years short of the required minimum age to be licensed. While at Columbia University in New York for doctorate studies, Pearl Harbor was bombed. He enlisted with the 2nd Philippine Regiment and because of his facility with languages, was sent to Japanese Language School to learn Japanese and then sent to India to break Japanese war-time codes.

SyCip could have stayed on in New York after World War II, but he chose to return to the Philippines to help rebuild his war-torn country. At the age of 25, he opened a one-man accounting office in the Binondo district while teaching at UST. In 1947, SyCip’s fledgling accounting firm expanded to become SyCip Velayo Jose & Co. after SyCip took in Vicente Jose and his bosom buddy Alfredo Velayo.

Tom Fernell, a Scottish accountant, decided to return to his homeland and negotiated to merge his practice with Sycip’s on condition that his two Filipino accountants – Arsenio Reyes and Ramon J. Gorres – would be SyCip’s partners. From this relationship, the largest accounting firm in the Philippines – SyCip Gorres Velayo & Co. – derived its current name.

In 1966, SGV institutionalized social responsibility by organizing the SGV Foundation, through which the company donates professional services to nongovernment organizations devoted to civic affairs and social problems.

Schools were his favorite beneficiaries of grants and endorsements. SyCip believed that education, more than any other form of support, was what will “lift Filipinos from poverty,” and improve the Philippines’ economic profile.

In 1968, SyCip, together with Ramon del Rosario Sr., formed the Asian Institute of Management, a region-wide institution guided not only by a Filipino board of trustees, but also by a board of governors drawn throughout Asia. SyCip held the position as founding chairman of AIM until his retirement in 2001.

Both the SGV and AIM are among SyCip’s crowning achievements. The two institutions have greatly enhanced the Philippines’ image abroad, training professionals to be at par with graduates from the best international business schools.

[Original research for this piece from various sources and from a personal interview by the author in April 2009 was done for a biography contributed for the Southeast Asian Personalities of Chinese Descent: A Biographical Dictionary by the Chinese Heritage Center of Singapore in 2012. This is a revised and concise version of the original. Photos from Wash: Only a Bookkeeper, a biography of Washington Z. SyCip by Jose Y. Dalisay Jr., 2009].