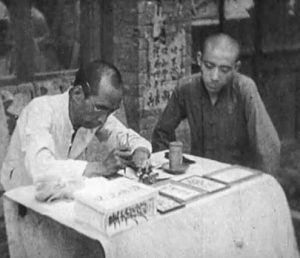

My first encounter with the profession was at the Bahay Tsinoy, a museum of Chinese in Philippine life. One prominent life-sized figure depicted a late Spanish or early American era man dressed in Mandarin garb, sitting at a desk with ink brush and paper. The caption reads: “A public reader in Manila. For a fee, he reads and writes letters for illiterate Chinese.”

Such writers are employed by remittance companies called qiaopi agencies (僑批館) . These businesses are mostly located in Chinese enclaves in major cities and would usually have their corresponding branch offices in mainland China. They were responsible for distributing letters with money remittances to poor villages in the mainland, and delivering back the letters of response with receipts to their senders.

Many of the overseas Chinese in the small towns and villages in the Philippines were illiterate. Thus, the few literate ones in the community were essential to maintaining communication between the overseas Chinese and their families in the mainland.

Such letter writers were usually close family friends, a Chinese teacher at the nearest Chinese language school or a business associate, who usually did not charge for their services.

There seems to be few written records about letter writers. Luckily, I came across one rare story, “Letter Writers,” an online article by Naidu Ratnala Thulaja. According to the article, the writers were mostly men, as it was mostly males who received education in old China.

I am fortunate to know of one special letter writer that deviated from this norm. We do not have a single picture, nor even the person’s real name. A lot of things about this writer’s life comes only by speculation.

For one thing, this letter writer is a woman! Another curious aspect is that though she lived and worked in mainland China, she is not known to be associated with any qiaopi agency.

I came to know about her during my quest of reuniting elderly siblings and cousins from the Chan family who once lived in Eni village near Quanzhou City, Fujian province, China. A relative briefly mentioned to me about a letter writer and how she frequently sent letters to the Philippines on behalf of her husband.

The lady letter writer’s Chinese name is An Lang Co (安朗姑), but there is no way to know if these are the correct Chinese characters, since it is just based on how the name is pronounced in Minnan 閩南 (or Hokkien) language.

Her surname An (安) is pretty rare. It is ranked 110th among the most common Chinese surnames in the world and mostly found in northern China, not in the southeastern Fujian province where An Lang Co lived.

Is it possible that her full name is a “Filipinized” Chinese surname Anlangco or Anglangco? She could be Filipina in this case, as is the case with my Filipina great-grand aunt who got trapped in the mainland. It could also be her name is An Lang for the Co (姑) also means auntie.

In the absence of a picture, we can only imagine what An Lang Co looked like from the memories of those who dealt with her. In the 1980s, she was already elderly, slim and tall – she stood at 5.6 feet, which was pretty much above the average height of Chinese women of that era. She had a slight stoop but was neat and tidy looking. Her eyes were black. She could be a Chinese mestiza since her skin was dark and her hair was long and wavy, which she always tied in a bun.

While there were surely many people who could read and write Chinese in China, what made her more unique is that she mostly wrote in English, though she may have read and written Chinese letters too. But being skilled in English was rare and she may have been the only letter writer in the city who could read and write English. And she not only wrote letters, she also read them.

From the demand for English translations, one can surmise that her mainland Chinese clientele mostly communicated with their families in the Philippines, a country where more than half of the ethnic Chinese population had roots in the towns and cities under the administration of Quanzhou. Also, most Filipinos communicated in English.

Letter writing may have been her only source of income. Each letter, regardless of the number of pages, cost about 10 yuan. Her patrons also had her read letters written in English. Most interestingly, she also read letters in Filipino. She charged the same rate for reading as well as writing a letter. In the beginning, she helped people write letters in a nondescript shop. Later she worked from her home.

Personal sacrifice

She was a jolly, enthusiastic, very talkative and nice person, although she seemed to have led a rather sad life. My relative mentioned that An Lang Co never married. She lived alone in Houcheng (後城), which is in downtown Quanzhou. Perhaps, her father was also Chinese. We don’t really know if she was born in the Philippines, we just know she went back to China from the Philippines but the reason is unknown. She seldom talked about her past.

Her good grasp of English indicated she had a good education, perhaps in the Philippines. But her reasons for moving back to China remain a mystery.

During my crash course in Mandarin at Chiang Kai Shek College in 2006, I was referred to Dr. Gilbert Go, one of the few persons I know who could read kansia (simplified) script, to read some of the letters our family kept.

He mentioned that the letters we have were most probably not written by our relatives but by a literate person. He explained that these writers, during the Cultural Revolution, did so at great risk.

During the revolution, many educated people such as those who could speak Western languages like English were persecuted as propagators of Western ideology. Persecution involved public humiliation, re-education through manual labor in the country side, torture and even death.

End of an era

Thulaja mentioned in his article that there are still professional letter writers in Singapore today, but they are dwindling due to various reasons: technological developments that provide better alternatives to communication; the passing of the elders and the younger generation’s disinterest in continuing contact with their Chinese mainland kin and the increased literacy rates among the new generation today, so most Singaporeans can now write letters on their own.

In the Philippines, with the closure of the remaining qiaopi agencies in the 1980s, professional letter writers have ceased to exist.

I have a friend whose father was a former letter writer in a qiaopi agency in Manila’s Chinatown. With his father’s fading memory, all those family secrets that he accumulated from writing correspondences will be gone when he passes away.

Indeed, with the passing of these letter writers, the hope of so many families to maintain that link with their kin ends. In my hometown for example, I’ve heard so many friends and relatives mention the name Intsik Juan whenever the topic of finding relatives comes up. He was our town’s only letter writer (and at times even letter courier). He was fondly remembered because he did it for free. In our town, so many family links had been cut and lost when he passed away.

Sometime in early 1980s, An Lang Co died. She was about 70 years old then. Her passing must have been terrible for many families in Quanzhou City and nearby villages, who had no one to help them write and read letters. This resulted in some families losing contact with relatives in the Philippines.

Legacy

I have often wondered if the first letter from China I read two decades ago written in beautiful penmanship was written by An Lang Co? How many other letters that I came across in trying to find lost relatives of families in China and the Philippines were written by her?

In any case, having experienced firsthand the power of translation, I have a deeper sense of respect for this old lady who was able to connect her clients with their loved ones who lived far away in another country. For some families, the letter writers gave them voice when time and space could not.

An Lang Co and the letter writer’s impact are fleeting yet immense. These simple and short-lived actions touched the lives of many families both in China and in the Philippines, providing a link that kept families together.