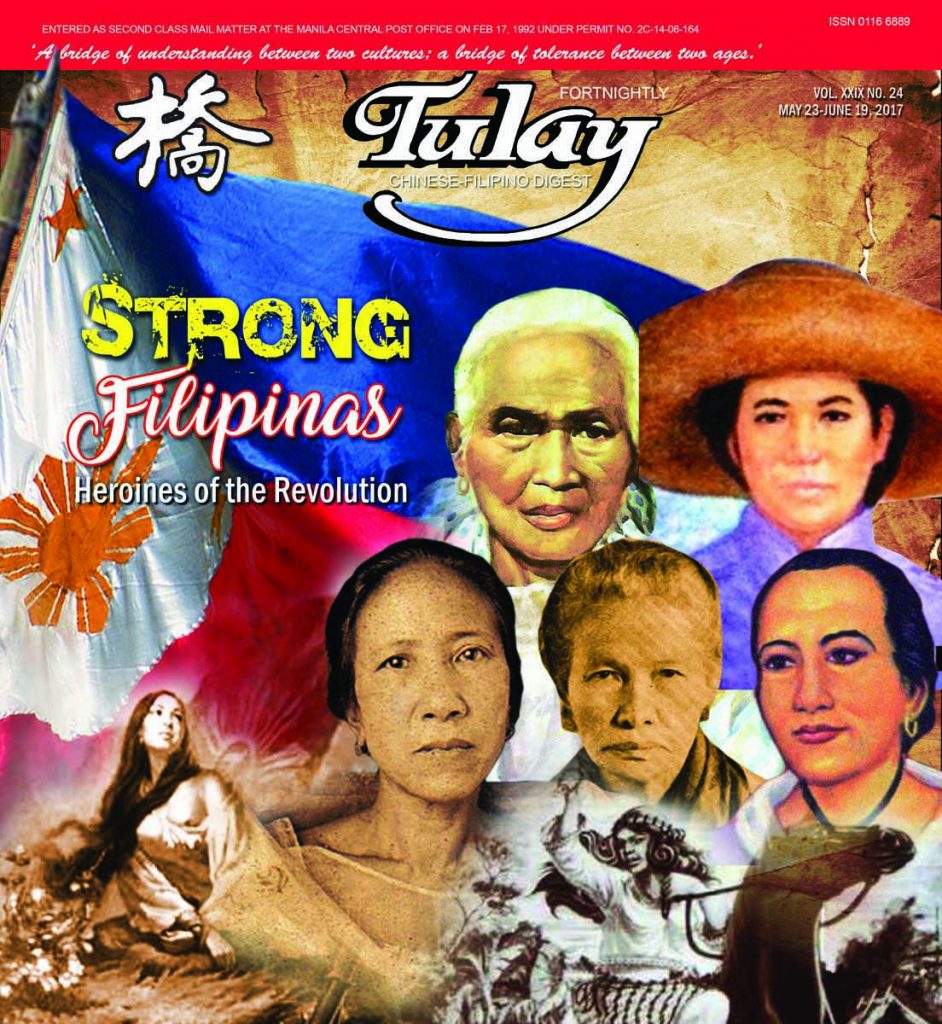

Much has been said of women’s roles in family, society and country. Much has been said to promote gender equality, protecting human rights of women, specially those in marginalized sectors of society. Without a doubt, women play a vital role in the nation’s life. They have moved beyond traditional roles of wife and mother to contribute to culture, the economy and politics. Yet, a journey through the country’s historical annals shows that the image of Maria Clara — frail and demure — did not always hold true.

Here are some outstanding Filipinas — heroines and mothers — who took active roles in rebellion against Spanish colonial overlords during those tumultuous years that led to the Philippine Revolution of 1896.

Gabriela Cariño Silang, Ilocos Joan of Arc

It was fate that made María Josefa Gabriela Cariño Silang best known as the first female leader of the Filipino movement for independence from Spain. This Spanish mestiza received an elementary-level education at her town’s convent school. She was born in 1731 in Santa, Ilocos Sur to a Spanish trader Anselmo Cariño, who plied his trade from Vigan to Abra along the Abra River. Her mother was Tinguian – Itneg –from what is now Pidigan, Abra.

Separated from her pagan mother in childhood, Silang was raised a Christian by a priest. At the age of 20, her father forced her to marry Tomas Milan, a wealthy businessman who died three years later.

In 1757, she married Diego Silang, whose assassination in 1763 led her to take on his role as a revolutionary leader. As commander, she effectively led the Ilocano rebel movement for four months before she was captured and executed at 32 by the Spanish colonial government.

Diego had gambled and sided with the British during the latter’s short-lived occupation of the Philippines (1762- 1764). Made governor by the British, he was promised reinforcement to push out the Spaniards in Ilocos. But the help never came.

During this revolt, Silang became one of his closest advisors and his unofficial aide-de-camp during skirmishes with Spanish troops. She was also a major figure in her husband’s collaboration with the British occupiers.

Spanish authorities retaliated by offering a reward for Diego’s assassination, which led to his betrayal by his own friends. He was just 32.

Silang fled to Tayum, Abra and sought refuge in the house of her paternal uncle, Nicolas Cariño. There, she later assumed her husband’s role as commander of the rebel troops. She appointed her first two generals, Miguel Flores and Tagabuen Infiel. Her popular image as the bolo-wielding la Generala on horseback stems from this period.

Silang successfully led her men through their first battle in her hometown, Santa. Their devastating loss against the rebels made the Spanish determined to defeat her.

Silang and her men went to Pidigan, Abra to establish a new base. While there, she was reunited with her mother.

She was joined by her uncle, Nicolas Cariño, who temporarily took command of the rebel forces gathering 2,000 men loyal to her husband. Silang and her troops descended on Vigan on Sept. 10, 1763 then led several attacks against Spanish forces. Her forces were eventually overwhelmed. She was captured later in the mountains of Abra and taken prisoner by Spanish forces led by her husband’s assassin, Miguel Vicos.

To teach the rebels a harsh lesson, Spanish authorities had her executed by public hanging in the town plaza. The brave heroine, then only 32 years old, went calmly and courageously to her death. To this day, the final resting place of Gabriela Silang remains unknown.

Tandang Sora, Mother of Philippine revolution

If she had lived during peacetime, Melchora Aquino might have been a community leader, active in public events.

She learned to read and write at a young age, often took part in her barrio’s Santa Cruzan festival, and had a good singing voice. She was often invited to lead many Holy Week pabasa.

Aquino was born on Jan. 6, 1812 in Balintawak, Caloocan to well-off parents, Valentina de Aquino and Juan Aquino.

Her husband Fulgencio Ramos was a cabenza de barangay. Widowed early, Aquino raised their six children and managed the farm and businesses her husband left behind.

She earned the moniker Tandang Sora because of her age. She was 84 on Aug. 23, 1896, when Andres Bonifacio and more than 1,000 fellow revolutionaries tore up their cédulas and shouted “Long live the Philippines!”

This event, now known as the Cry of Balintawak, marked the beginning of the rebellion against Spain. This historical event happened in the yard of Juan Ramos, Aquino’s son, in Pugadlawin. Thus, the event is also referred to as the Cry of Pugadlawin.

The next day, at her home, Bonifacio and his men had their first skirmish with the Spanish civil guards and soldiers. This clash marked the beginning of the struggle for liberation.

In the wake of open rebellion against Spain, Aquino opened her sari-sari store in Balintawak to the Katipuneros and gave them 100 cavans of rice, 10 carabaos and other essential supplies. In keeping with her reputation for kindness and generosity, she welcomed the sick and wounded and tended to them at her home.

Aquino was later captured by the Spaniards in Novaliches and interrogated in Manila’s Bilibid prison about other Katipuneros but she did not divulge any information. She was sent with other revolutionists to exile in Guam.

She returned home six years later with other exiles on board the USS Uranus on Feb. 26, 1903 during the American regime, poor and aging.

However, she refused the rewards and assistance offered by the government for her exemplary role in Philippine history.

She died in 1919 in her daughter’s home. She was 107. She was buried in the Mausoleum of Veterans at the Manila North Cemetery until 1969. Then, her remains were moved to Himlayang Pilipino’s shrine to Filipino heroes in Tandang Sora, Quezon City.

To honor her, a Quezon City district and an avenue were named for Aquino. Her profile was also placed in the Philippines’ five-centavo coin from 1967 to 1992.

Aquino is the first Filipina who appears on a Philippine peso banknote, in this case, a P100 bill from the English Series (1951–1966). As well, Tandang Sora Street in San Francisco, California is named in her honor.

Gregoria Álvarez de Jesús, Mother of the Katipunan

No ordinary wife and mother, Gregoria de Jesus was considered mother of the Katipunan. She was custodian of the Katipunan’s seal and documents. She also founded the movement’s women’s chapter.

At 18, Gregoria de Jesus married Andres Bonifacio, leader of the Philippine revolution. Their wedding was attended by all the top leaders of the Katipunan, including Josefa Rizal.

If there was a honeymoon, it was short-lived. Living in the heart of the revolution, with a man wanted by the authorities, she faced constant danger with courage. After the Katipunan was exposed, the couple was targeted by the Spanish authorities for capture and execution. Her father and two brothers were arrested.

Bonifacio escaped to the mountains of San Francisco del Monte. Aling Oriang, as she became known, moved from house to house and assumed different identities to safeguard Katipunan documents. She suffered great difficulties carrying out tasks assigned to women who could more easily move around undetected. At great risk to her life, she later joined Bonifacio in his mountain refuge.

As a soldier, she learned to ride and to shoot, slept on the ground, suffered hunger and thirst, and mastered evasive tactics. The revolutionary generals spoke admiringly of her extraordinary courage and daring and of her alertness which saved her from capture.

After Bonifacio’s death, she married Julio Nakpil, one of the generals of the revolution. She had one son, Juan, from her marriage with Bonifacio, and five more children with Nakpil.

Born on May 9, 1875 in Caloocan, De Jesus came from a middle class, pious Catholic family. Her father Nicolas was a master mason and carpenter, as well as a gobernadorcillo during the Spanish regime.

Her mother, Baltazara Alvarez Francisco of Noveleta, Cavite, was the niece of General Mariano Alvarez who led the revolution in Cavite.

She received public schooling, but her education was truncated in her early years, even though she was a bright student. She once received a silver medal for excelling in an examination given by the Governor-General and the town curate.

Out of school, the young De Jesus often went to the countryside to supervise the work on the family rice fields, worked with tenants and laborers, and paid the workers’ wages. She also did sewing and weaving at home. She died in 1943, in the home of her only son Juan, during the Japanese occupation.

Trinidad Tecson, Mother of Philippine Red Cross and Mother of Biak na Bato

Trinidad Tecson (1848-1928) was of middle-class origins, born in San Miguel, Bulacan, one of the 16 children of Rafael Tecson and Monica Perez. She learned to read and write from the schoolmaster.

As a child, she joined in boys’ games and learned fencing with Juan Zeto. She was called Tangkad (tall) by her peers and became known for her physical bravery. She was feared throughout the province especially after she successfully defended herself against harassment by several officers of the guardia civil.

She married at 19. She and her husband were traders of cattle, fish, oysters and lobsters to be sold in Manila.

In 1895, she moved to Manila where she joined the Logia de Adoption, a masonic lodge for Filipino women founded in 1893.

She earned the titles “Mother of Biak-na-Bato” and “Mother of Mercy” by fighting 12 battles with five Filipino generals – Mariano Llanera, Francisco Makabulos, Isidro Torres, Gregorio del Pilar and Emilio Aguinaldo.

She organized groups of women to nurse wounded Filipino soldiers and was cited as the Mother of the Philippine National Red Cross for her service to fellow Katipuneros.

At 47, she joined the Katipunan and signed her oath with her own blood, although women members did not have to. She was involved in several raids against Spanish arsenals to get weapons for the revolutionary cause.

Once, during the battle in San Miguel, she was delivering food to the troops and she avoided capture by playing dead. In battle, she was hit on her right thigh and forced to retreat with other revolutionaries to Aguinaldo’s headquarters in Biak-na-Bato.

After Aguinaldo established the Malolos Republic, she served as the Commissary of War.

During the Filipino-American war, she joined the revolutionary forces led by Gen. Gregorio del Pilar and was in the assault on Bulacan.

When the American pursued the revolutionists to the north, she brought with her the sick and wounded revolutionaries, crossed the Zambales mountains to Sta. Cruz, then to Iba. She took part in numerous guerrilla skirmishes against the Americans. She fell ill and became demoralized by continual retreats and had to accept the American victory.

In her lifetime, Tecson married four times. She had two children from her first marriage, both of whom died. She remained childless through her subsequent marriages, and in 1928 died at the Philippine General Hospital. She was buried at the mausoleum of the Veterans of the Philippine Revolution in Manila’s North Cemetery.

She was 79.

General Agueda Kahabagan, Tagalog Joan of Arc

Filipinas shone during the revolution, many earning recognition as our local versions of the French heroine Joan of Arc. From the Tagalog area came Agueda Kahabagan y Iniquinto, whose courage earned her that nickname as well.

Kahabagan was the only female general in 1899’s roster of generals in the Katipunan.

Little is known about her. She was believed to be from Sta. Cruz, Laguna, Her bravery in battle was legendary. She had fought in the Philippine Revolution, and the Filipino-American War.

An article on “Philippine Heroines of the Revolution: Maria Clara they were not” by historian Dr. Robert L. Yoder, Kahabagan was described as a formidable female military figure.

“Dressed in white and armed with a rifle and bolo, history records her bravery in frequent combat against the Spanish and American forces. General Miguel Malvar commissioned Kahabagan to lead a formidable detachment of forces armed with rifles and machetes.”

She fought under Malvar in May 1897. In October 1897, Kahabagan fought under General Artemio Ricarte, whose troops successfully recaptured the Spanish San Pablo garrison.

Oral history among elders of San Pablo recall her jumping over trenches high and wide on horseback, holding a gun in one hand and a dagger in another.

Having survived the battles against Spain, she then joined Gen. Pio del Pilar in his battle against the American Forces in the Southern Tagalog region.

It was probably Del Pilar who recommended that she be given the honorary title of Henerala. Records show her appointment to the post on Jan. 4, 1899, making her – at the time – the only female on the army’s roster of generals.

Despite her daring and courage during the battles for independence from two western colonial powers, Kahabagan’s name has all but faded from the memories of modern day Filipinos.

Teresa Magbanua, Visayan Joan of Arc

A school teacher who became a military leader, Teresa Magbanua was among the few women to join the Panay-based Visayan arm of the Katipunan. Magbanua was credited as the only woman to lead troops in the Visayan region during the Revolution and later against American colonial forces during the Filipino-American War.

She was born in 1868 of a wealthy, socially prominent family in Pototan, Iloilo. She was given a good education in Jaro and then Manila.

As a child, she loved to climb trees, ride horses and carabaos, and swim in the river. She retired from teaching after marrying Alejandro Balderas, a wealthy landowner-farmer from Sara, Iloilo.

Taking eagerly to farm life, Magbanua taught herself to shoot and to ride and became a good horsewoman and markswoman.

She joined the revolution but she had to overcome the resistance of local military commanders, and of her husband, who opposed her involvement in a military capacity

Magbanua had two younger brothers in the revolution, both of them generals. Devastated by their deaths, she took up arms against the Spaniards.

She sought the blessings of her uncle Gen. Perfecto Poblador. He reluctantly allowed her to lead troops into combat and won several battles under the command of General Martin Teofilo Delgado.

On Dec. 31, 1898, Magbanua led troops against Spanish forces at the Battle of Sapong Hills near Sara. Despite odds and superior arms of the Spanish forces, Magbanua prevailed.

After these battles, Magbanua’s forces were joined by revolutionary forces from Antique. Along with the other generals, Magbanua helped circle Iloilo City, allowing Delgado to enter and retake the city from the Spaniards.

During World War II, she provided supplies to guerrilla fighters in the resistance movement against the Japanese. Shortly after war broke out, her husband Balderas died. She sold her properties in Iloilo to finance the guerrilla resistance.

However, by the end of 1900 the American infiltration into Panay was virtually complete, yet Magbanua refused to surrender, maintaining guerrilla forms of resistance. Finally, she disbanded her troops and retired to Sara.

After the war, Magbanua moved to Zamboanga del Sur to live with her sister, Maria, in Pagadian. She died childless in August 1947, her burial unannounced and attended only by close friends. She had earned the distinction of having fought the Spanish, Americans and Japanese conquerors.

She was 78.

Sources and references: The following are helpful resources on this topic: Teodoro Agoncillo, “The Revolt of the Masses;” Reynaldo Ileto, “Pasyon and Revolution: Popular Movements in the Philippines;” Christine Doran, “Women in the Philippine Revolution,” www.philippinestudies.net/ojs/index.php/ps/article/…/696; www.choosephilippines.com/specials/people/133/visayan-joan-arcwww.msc.edu.ph/centennial/gdjesus.html; www.bayaniart.com/articles/gabriela-silang-biography/